-

France’s Lascaux cave museum celebrates 10th anniversary with year of events

The International Centre for Cave Art contains a full-scale replica of France’s famous cave paintings

-

Paris exhibition shows Napoleon’s final will

58-page document covers Emperor’s final wishes expressed in exile

-

Petition to save dog accused of killing French woman reaches 30,000 signatures

Public prosecutor recommends Curtis be euthanised to avoid further incidents

French Palaeolithic cave art shows deep human connection with animals

Nature watcher Jonathan Kemp goes underground to marvel at the bison, deer and aurochs drawn 14,000 years ago

Deep inside an Ariège mountain, about an hour from the Mill, is a cave that I think of as a womb; it is called la Grotte de Niaux.

The 800 metre walk from the surface car park halfway up the mountain is through windings of labyrinthine complexity; sometimes wide subterranean river-gouged caverns (these caves are always found in limestone country, which is a water-soluble rock) sometimes tight passages where you have to be careful not to knock your head.

Prehistoric cave art is never completely understood

The small group, never more than 25, inevitably talks in hushed tones; to be in such a place elicits a sense of awe.

You are, of course, with a competent guide, often an archaeological student.

I have been several times over the years and they are always knowledgeable and engrossed in their subject.

They stress, however, that there remain many aspects of the ingress by humans there that will never be completely understood.

Niaux, and the other examples of prehistoric cave art, will always hold their secrets. We are, after all, witnessing something many, many thousands of years old.

Read more: Climate change threatens ancient drawings inside French cave

A gasp of astonishment at what we saw

Arriving, finally, in a large domed chamber, known as the ‘salon noir’, the guide asks everybody to extinguish their lamps.

The silence and the darkness are the most profound that I have experienced. We had been positioned by a railing, and when the guide illuminated the side walls of the cave the most wonderful line drawings emerge out of the rock.

There was a gasp of astonishment at what we saw there.

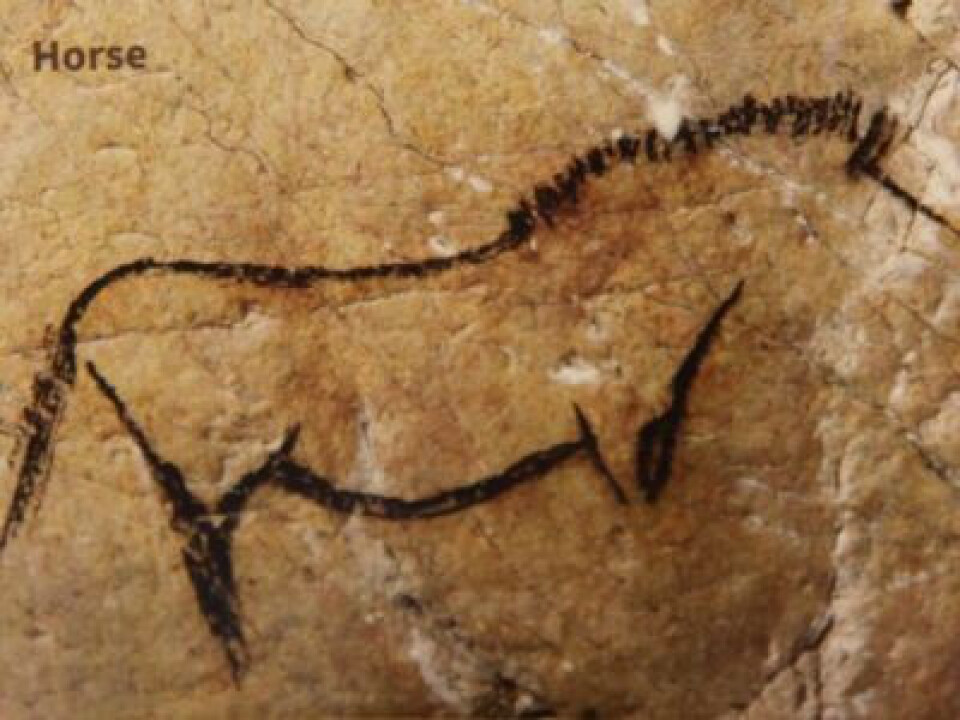

Photo: Depiction of a horse: Credit: Sites Touristique de L’Ariège

They are made with black lines, drawn with the assurance and precision that you see with truly great artists.

They are of animals, some of which have long disappeared from the modern countryside. There are bison, horses, ibex, a deer.

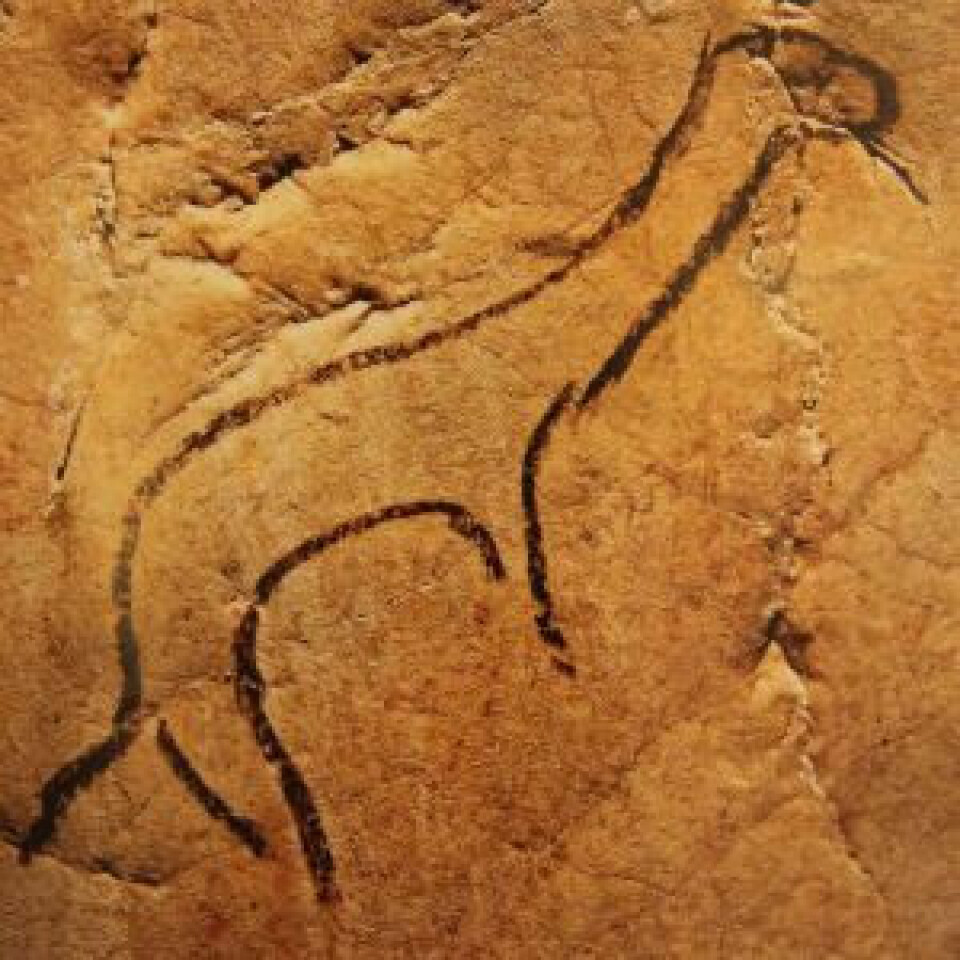

There are other representations in the part of the cave that is currently closed to visitors – a weasel, which is only depicted in Niaux and nowhere else; and aurochs, a large cattle ancestor which has been extinct since the 17th century.

Photo: Rare depiction of a weasel; Credit: Sites Touristique de L’Ariège

Drawings are 13,000 to 14,000 years old

In Niaux, there are no human forms – these are rare in Palaeolithic art. There are, however, many geometric forms, some in a red pigment: a series of dots, a vertical stick with a loop to one side called a claviform, and a barbed sign vaguely representing an arrow.

The meanings of these signs are obscure; perhaps they are coded messages for others to read. However, there are over 500 human footprints in the currently inaccessible part of the cave, waiting for sufficient funds to become available for a thorough scientific study.

Photo: A vertical stick with a loop to one side called a claviform; Credit: Sites Touristique de L’Ariège

You are looking at paintings 13 or 14 thousand years old, drawn by Magdalenian homo sapiens people, our direct ancestors, and now known to have been created over almost a thousand years of different visits to these caves.

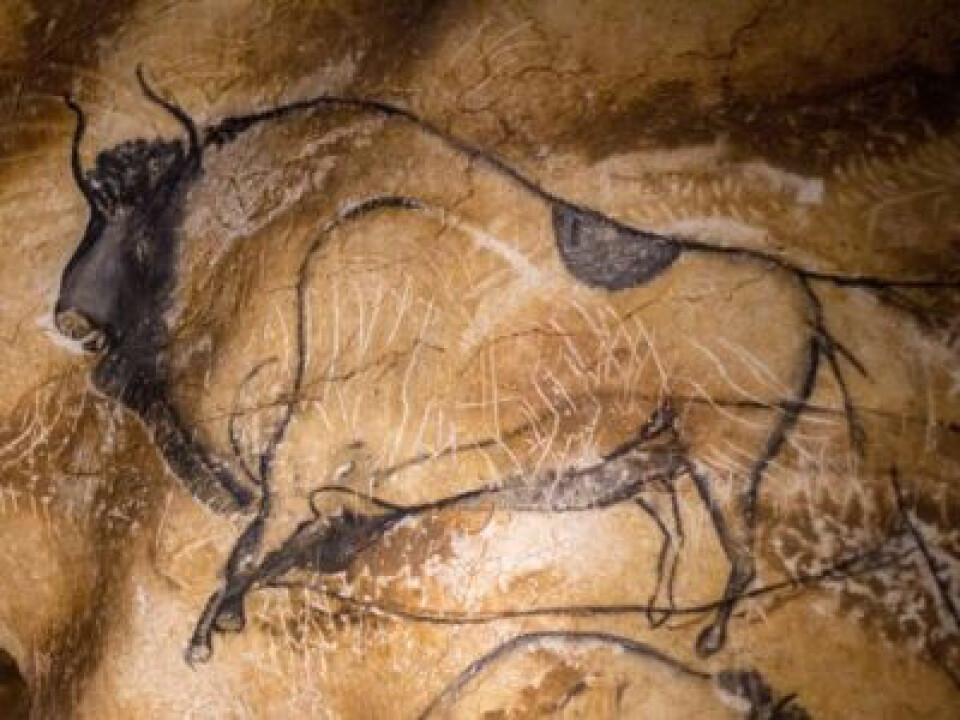

Other caves containing Parietal (wall) art, such as the Chauvet caves in the Ardèche, are much older, a staggering 33,000 years before the present.

It is impossible for the public to visit Chauvet as it is considered necessary to preserve it in pristine condition, but a facsimile – apparently very good – has been constructed.

Photo: Bison drawing in the Chauvet caves in the Ardèche; Credit: Bruno M Photographie / Shutterstock

Identified with animals in order to hunt them

Sometimes the artists used the form of the rock to suggest the natural shape of the animal – the curve of a bison’s belly for instance.

Some are staggering in the life force that emerges from the rock, others are not so well drawn. Oddly, sometimes they are superimposed one over another, and the scale varies widely.

Obviously, the animals depicted were prey for the people who painted them; some of the flanks seem to be pierced by spears, and parallels with other hunter-gatherers’ practices show that an intense identification with the animals is considered a necessary preparation for success in this difficult and dangerous pursuit of high-value food.

It is interesting to note, however, that the animals depicted were not the usual prey for these people, which is known to have been reindeer.

Read more: Bellegarde dig shows France’s evolving approach to archaeology

Was going into the deep, dark cave an initiation ceremony?

The question remains as to why it was considered necessary to travel so deeply into the cave system to make these drawings. Clearly more was going on than just preparations for a hunt.

I have asked myself what are the reasons behind such an undertaking. There is, perhaps, a clue in the feelings that I experience when I finally emerge into the normality of daylight, warmth and the expanse of the surface world.

There is a sense of relief, as if a trial has been successfully passed through. Perhaps this hints at there being elements of an initiation rite for the people that undertook the hazardous journey into the deep mountain (without all the security of modern lighting methods which can be relied on to last the time that a visit takes).

These people were totally immersed in nature, and it is now generally recognised that there is a shamanistic element in similar practices that anthropologists have encountered in other tribal cultures.

Read more: 15 leave French cave after 40-day experiment without light or clocks

The danger that had to be confronted by the shaman and his acolytes, the submersion in the deepest bowels of mother earth for what must have been considerable lengths of time, are factors that contribute to the intensity of their experience and may lead to altered states of awareness.

Thus I can well imagine the anxiety, if not terror, that a young person would have to confront if left alone with a spluttering torch and no reliable memory of how to find their way back to the surface and the comfort of family.

Throughout many cultures, initiation was an important step often undertaken as a doorway into adulthood, and indeed some tribal people still maintain these rites to this day, despite disapproval from governing authorities. They can be very dangerous.

Cave visited for many generations

There can be little doubt that these caves represented sanctuaries to the people that penetrated them in the deep past.

Carbon dating of the various pigments used for the paintings has shown that this was a practice that continued for nearly a thousand years, from 13,850 years ago until 12,890, perhaps not continuously but certainly in two distinct phases.

There was, therefore, a memory that lasted many generations and a cultural intention to access this difficult place which was not in the slightest way casual.

Related articles

Explore France’s geological triumphs and curiosities with new website

Metal detectorists in France reject ‘looter’ label in French crackdown

Explore the sites to see the legacy of France’s glorious Roman past