-

Death charges claimed by French banks to be restricted

New law passed by the Senate in early summer

-

Electric bike popularity in France opens way for new insurance deals

Number in country rockets as theft policies evolve

-

What is France’s ‘intime conviction’ legal concept used to reach verdict in Cédric Jubillar trial?

Unique approach to murder trial without a body that transfixed France

How is France tracking spread of Indian variant of Covid-19?

France has reported very few cases of the variant compared to the UK. Some UK media suggest it is because of its advanced sequencing capabilities, meaning it discovers more cases. Is this correct?

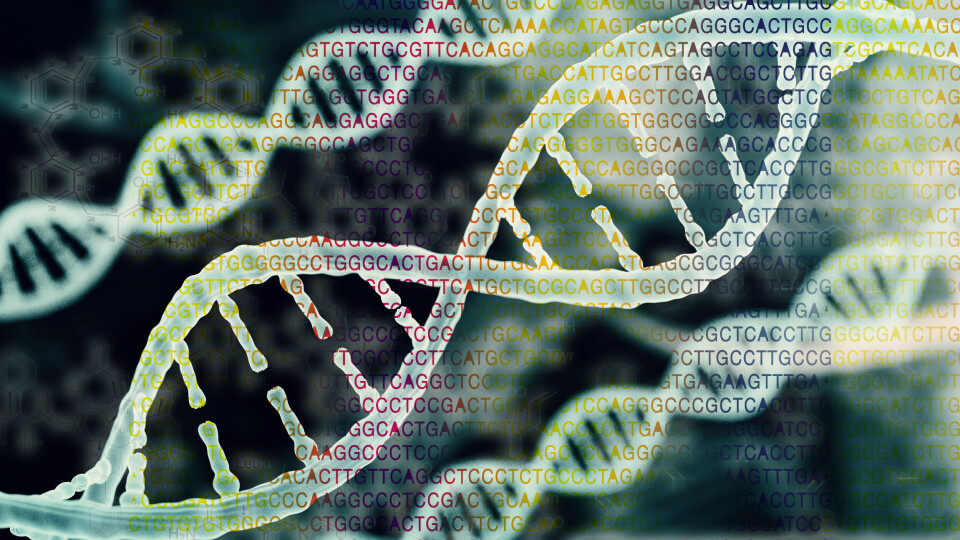

Sequencing - a word widely used since the Covid-19 pandemic began but whose meaning is lost on most people - refers to genomic sequencing.

France recently banned people in the UK from entering the country for all but essential reasons due to the spread of the Indian variant of Covid-19 there.

Some UK media have reported that the UK only has more cases of the variant because of its greater facility to carry out sequencing. It is very difficult to assess this accurately but it is possible to look at testing and sequencing in both countries and to see that this is unlikely to be the case.

What is sequencing?

It basically means identifying the genetic makeup of the virus found on, for example, a positive PCR test, as opposed to testing to see if a particular variant is present.

A positive PCR test is processed (to identify RNA molecules) and then converted into DNA that can be read so scientists can see the genetic makeup of the virus.

It can be compared to other samples and allows scientists to track how the virus is mutating, which the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 has already done, thousands of times.

Through sequencing, scientists can see if a sample has the mutation found in the Indian variant of SARS-CoV-2. The Indian variant’s scientific name is B.1.617, and there are three sub-strains of it: B.1.617.1/2/3. The mutation common to the variant is known as L425R.

The strain B.1.617.2 is the one that is spreading quickly in the UK at the moment.

Some experts, such as Professor Ravi Gupta, a member of the UK government's New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group, have estimated that this strain makes up 75% of all new Covid-19 cases in the UK.

This is also the most commonly detected strain of B.1.617 in France, making up 36 of the 46 small groupings of the variant so far detected in France. France is tracking the strain by groupings, rather than individual cases. A grouping usually refers to a household, made up of two, three or four people.

The UK is a world leader in sequencing, allowing the country to build up a solid picture of the types of all the Covid-19 variants spreading there. It has also excelled on collecting, presenting and sharing data related to sequencing, through its COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium (COG-UK).

This is a group of public health agencies and academic institutions in the UK created in April 2020 “to collect, sequence and analyse genomes of SARS-CoV-2 as part of COVID-19 pandemic response,” according to its website.

The UK has sequenced a total of 498,909 samples of coronavirus genomes, since the start of the pandemic. As of early May, France had sequenced around 44,000.

Professor Karine Lacombe, head of the Infectious Diseases Department at Hôpital Saint-Antoine in Paris, admitted that English-speaking countries such as the UK and the US are better at sequencing than France, in an interview with BFMTV on May 16.

But she said France is making progress.

“Now there are more laboratories...that allow us to have more sequencing data,” she said.

“We are not yet at the level of the UK or the US...but a lot of progress has been made.”

France has four main laboratories capable of sequencing coronavirus samples, and around 40 smaller laboratories.

Prof Lacombe said, “we have a pretty good picture of the spread of variants in France.”

In the week between May 17 to 23, 3,918 Covid-19 tests were sequenced out of a total of around 83,000 positive tests in France. This equates to around 4.7% of all tests.

Santé Publique France (SPF) considers 5% to be the minimum level needed in order to have an accurate picture of the spread of variants in France.

This means that France is close to being able to trace variants through sequencing alone, although still lagging behind the figures of the UK.

“We were late in 2020 and we underestimated the ability of the coronavirus to mutate,” said Dr Bruno Coignard, Director of Infectious Diseases at SPF, in an interview with the Huffington Post.

France only created its own equivalent to the UK’s COG-UK in January 2021, called EMER-GEN.

"Today, the theoretical sequencing capacity of the EMER-GEN consortium is 6,000 genomes per week,” Dr Coignard said.

SPF is aiming to be able to sequence 10,000 genomes a week by the summer, the Huffington Post reported. The UK’s largest sequencing centre, the Sanger Institute, is aiming to carry out 20,000 a week alone.

France then remains far behind the UK in terms of its sequencing capabilities, but is progressing.

Sequencing is not the only tool

Sequencing technology is not the only way of assessing variants of SARS-CoV-2.

There is also a technique called screening (criblage, in French).

All positive Covid-19 tests in France are subject to screening. This is where the tests are sent off and analysed for specific mutations. Currently, France is only able to detect mutations that occur in the original strain of the virus and the so-called UK, Brazil and South African variants.

SPF data from these screenings show that 77.6% of all positive tests in France are from the UK variant of the virus. Just under 6% of positive tests are from either the Brazil or South Africa variants.

This leaves around 16% of positive cases to be classed as unknown variants in France. It means that a maximum of around 16% of positive Covid-19 cases in France could be the B.1.617 variant. This is far lower than the 75% estimated in the UK.

Sibylle Bernard Stoecklin from SPF told the Huffington Post that in the next few weeks France would update the test kits it uses for screening to be able to detect the mutation common in the B.1.617 variant. This will mean that France will shortly have a more accurate picture of how many cases of the B.1.617 variant there are in the country.

The question of whether France’s low rate of the B.1.617 variant is down to its low sequencing rate remains very complicated.

The variant has been found in 10 regions of metropolitan France but so far the cases have mainly been limited to specific households where at least one member had recently returned from India.

France’s Conseil Scientifique, which advises the government on Covid-related issues, stated on May 28 that only a few cases of the variant have so far been detected.

Both the UK and France imposed strict travel rules on people coming from India around the same time – April 23 for the UK and April 24 for France.

However, stronger historical ties between the UK and India mean that there is likely more travel between those countries than between France and India.

In general, the total number of new Covid-19 cases in France is decreasing steadily each week.

Read more:

New UK to France Covid travel rules: Forms and 13 essential reasons

France ‘will avoid fourth Covid wave’ if next 10 days go well

France's ban on UK visitors is 'coherent' says Covid expert

Covid-19: What is the latest on the Indian variant in France?