-

Photos: 94 chateaux open their doors to visitors in Dordogne

The fifth Chateaux en Fête festival offers a chance to look around many impressive properties that are usually private

-

Martel: the medieval French town home to a 'truffle' train and lavender festival

The small town in the Lot offered refuge to an English throne heir until his death

-

Brittany lighthouse lens removal leads to public outcry

A petition gained over 20,000 signatures, highlighting the ongoing battle over the buildings' heritage in France

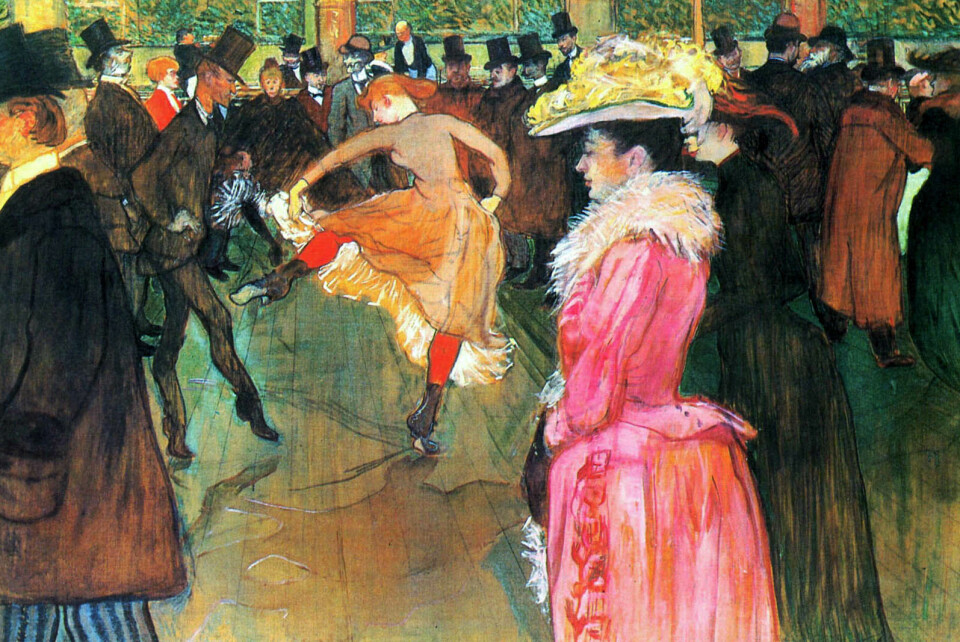

Did you know that the Cancan started out as a feminist dance?

Well before its association with the Moulin Rouge in Paris, the Cancan was known as a revolutionary and feminist dance

The Cancan gave women the chance to show they were no longer trapped in long skirts but could kick their legs about and did not need a man to partner them.

Its history has been researched by contemporary Cancan dancer and choreographer, Nadège Maruta, who recently wrote a book about her finds, L’Incroyable Histoire du Cancan.

She says the dance, criticised over the years for the revealing nature of its high kicks, developed from the formal Quadrille dance, popular in the early 19th century. In the 1820s, a new sequence was introduced, the cavalier seul, when the men were allowed a moment of exuberance dancing alone, throwing themselves on the floor and sliding across the dance hall.

This sequence was commonly called the chahut, meaning chaos, or cancan, after the noise made by parading geese or ducks. Women decided it was time they, too should be allowed to dance alone and introduce their own moves, and began their own cancan.

Shortly afterwards, in 1831, Nadège Maruta says the police tried to suppress the dance by trying to outlaw it. It was frowned upon in the press and the church preached against it. However, she says this made the Cancan a symbol of revolt and made it more rather than less popular as many women were fed up with social constraints.

It was particularly popular with the washerwomen in Montmartre, as it gave them a new way of earning a living, and the dance became more and more daring.

In 1857, one dancer, nicknamed Rigolboche introduced the rapid up and down movement of the legs.

In 1860, it had become so popular it became professionalised. The women were better paid than the men. Some became famous, and attracted nicknames like Nini Pattes En L’air, Môme Fromage and La Goulue, star of the Moulin Rouge.

Women were not expected to turn up to a dance without a man but La Goulue, or Glutton – so called because she would drink from cabaret client’s glasses during her performances – once arrived at the Moulin Rouge with a male goat, saying she preferred the buck because he smelled better. She was immortalized by Henri Toulouse- Lautrec in his paintings and posters.

In 1858, composer Jacques Offenbach wrote his popular burlesque comic opera, Orpheus in the Underworld. One of its melodies, the Galop infernal, was very quickly taken on at the Paris cabarets and has ever since been associated with the Cancan.

Gradually the dance developed to become what we associate with the Cancan now, frilly petticoats, high kicks and rousing music.

Related stories

New French regional languages law is 'politically historic'

Help is at hand: Mayday signal’s French origins explained