-

How to identify lounging lizards in France

Learn about the habitats and behaviours of diverse lizard species, from the common wall lizard to the elusive Western three-toed skink

-

The origins and long history of France’s unique wildlife officers

Connexion talks to Julien Nicolas, who fulfils a role created by Charlemagne in the year 803, tackling wildlife posing a danger to the public

-

France leads efforts to save critically endangered European mink from extinction

A reintroduction plan is in place to save the species, which is more threatened than the Giant Panda

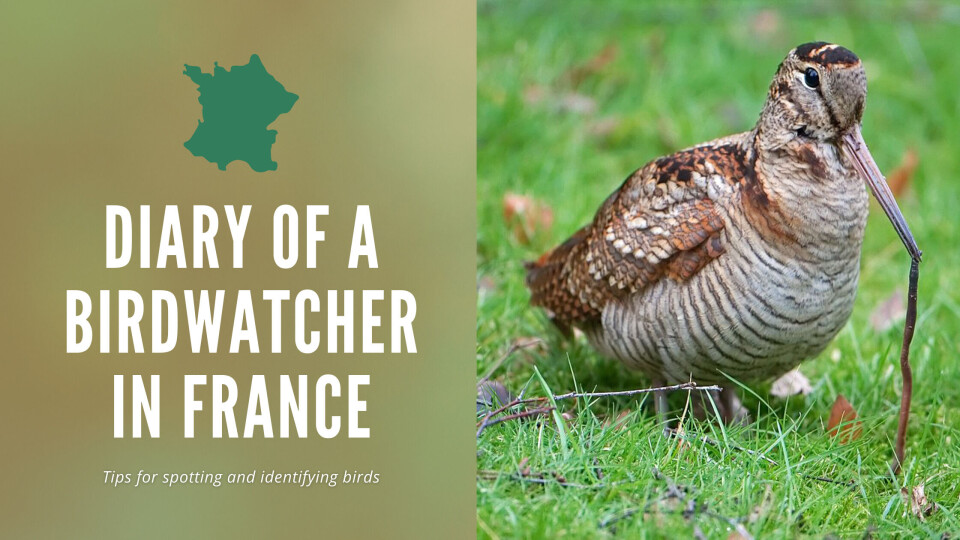

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: The Eurasian woodcock

The population of these elusive birds is on the decline in France due to hunting and destruction of habitat

A few days ago I saw a bird that I, and almost everybody else, rarely see. Walking on the wooded hillside above our mill in Aude, there was a burst of brown from the ground, a couple of quick wing jinks and… it was gone. A Eurasian woodcock (bécasse des bois in French).

They are really quite odd birds. They rest on the forest floor during the day, wonderfully camouflaged as dried leaves and so pass unobserved, coming out in the evenings to feed at night.

The population in France is relatively modest, and although it is possible to see them in any suitable rural habitat, the main concentration is in the eastern part of the country. The habitat to search for them is wooded, both deciduous and mixed, hilly countryside, with damp leaf-mould so the soil is soft enough for them to pierce with their probing beak.

If you are in the right place at the right time – spring evenings or dawns – they perform a territorial flight-circuit called ‘roding’. They nest from April to June, so this is the time to post yourself – at dusk is easiest – on a panoramic viewpoint and watch and listen as night falls.

The time I saw and heard this roding best was in Yorkshire and Scotland; every few minutes the bird would pass over us as he completed his laps, uttering a strange piggy grunt three or four times followed by a high pitched psipp sound, meanwhile flying fast in a straight line just above the treetops.

Unforgettable in the twilight, there was a special expectancy as we waited for him to come round again, and disappointment when he finally stopped as it fell dark.

The obvious feature of a woodcock is its long bill, tipped with a soft, prehensile end, which it uses for probing for food in the forest floor.

They are on the UK’s red list of threatened species. The European status is “of least concern”, but declining, and as they are a difficult species to observe it is very hard to estimate precisely the total population; somewhere in the region of 15 to 16 million.

The area they breed in stretches from the British Isles to the furthest east of Russia and northward to Scandinavian countries.

One, rather sad, statistic is that 3 to 4 million are shot every year in Europe.

As a result of the decline, France, at least, has made it compulsory to declare how many are taken each year by the hunting associations. There are moves to change the habit of using lead shot as ammunition to copper, to diminish the harm as it enters the food chain for many wildlife species, and, incidentally, those that consume them.

Woodcocks are hunted with dogs, to point and then flush from their hiding places. For this you need a well-trained gun dog, and in rural Aude the dogs are not trained for this. They are also trapped by wire snares, often used here.

They are traditionally cooked whole, with all the internal organs and brain left intact inside and, as their main diet is worms, they apparently have a very brown and earthy taste. No Frenchman worth his salt would refuse to eat a bécasse.

It is considered to be the best of the game birds. It is a good thing that they are so hard to find, and hard to shoot as the jink and rapid disappearance amongst the trees makes for a difficult shot.

As well as hunting, the other threats to this bird are loss of habitat – fragmentation of woodlands - and anti-parasite treatment of cattle so that the cowpats do not support the insect larvae that were formerly another important source of food for woodcocks. Changes to agricultural practice are slow, but eating organically produced meat and dairy produce is a choice that anyone can make to help wildlife.

The kiwi of the north

The Eurasian woodcock is the northern hemisphere’s equivalent to New Zealand’s kiwi, the flightless bird, also a night forager.

Research has been done on the ability of kiwis to find food – also mainly earthworms – with the conclusion that smell is the primary means by which they earn their living.

This has been monitored in aviary conditions by burying tubes of damp earth, some with worms in and some without. The kiwis went straight away for the worms, hitting the target without fail.

It is clear that different birds have widely varying senses; a raptor hunts by sight and has developed enormous eyes as a result while in the case of the woodcock, the initial probe seems to be directed by smell.

Unlike kiwis, though, they do have large eyes, which are needed for flying at dusk, nocturnal migration and watching out for predators, being placed high on the head they have an all-round upper vision.

Whilst feeding, sound and touch may also play some part, as has been suggested as a possible explanation for the behaviour of the American woodcocks, which perform a very peculiar formation line dance which a mother bird will teach her offspring.

It is believed that the heavy step forward could disturb the worms and make them move and so detectable by sound.

Sadly, I can find no mention that Eurasian woodcocks have learnt the steps so we are deprived of this extraordinary rhumba; but who knows what they get up to in the dark of the woods where they live?

There was also a legend, nowadays widely accepted and actually seen twice in one day by a friend – it must have been his birthday - and so confirmed, that woodcocks will pick up and carry their flightless young to safety, wedged between their legs and supported on their feet.

There are plenty of painted illustrations of this on the internet, but no photographs, so it must be a rare event.

Perhaps one possible benefit of Brexit could be that Italian hunters will no longer be able to travel to Scotland with their specially trained dogs to hunt woodcock and then return to Italy to eat them.

Unfortunately, the UK parliament’s refusal (so far) to license the British hunting estates, which charge high fees and is very big business, is an anomaly that has never yet been achieved, despite many years of lobbying from conservationists, so it remains to be seen if anything changes.

With the fact that Eurasian woodcocks are so difficult to see, I feel lucky to have seen this marvel of evolution as it disappeared into the forest.

Jonathan Kemp moved to France in 1989 and lives in the department of Aude. He has been volunteering with the French nature association the Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux (LPO) for the past 20 years, working on a variety of different projects.