-

'I helped restore French cathedrals as a female American stone cutter - despite prejudice'

Stella Cheng, who worked on the restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral, faced sexism and racism

-

French woman named one of world’s best teachers

Céline Haller, inspired by English and US teaching methods, has gained recognition for revolutionising learning with hands-on projects and inclusivity

-

What does a maître cirier do in France?

Exploring an ancient craft form at a company founded 120 years ago

Varian Fry: The American who was a ‘Schindler in France’

The journalist, whose story is to be dramatised by Netflix, helped save the lives of some 2,500 people at risk from the Nazis by smuggling them out of France to safer countries including the US

Article published September 30, 2022

American journalist Varian Fry – often compared to Oskar Schindler, the German industrialist who saved 1,200 Jews from the Holocaust – headed a Marseille-based network that saved 2,500 people at risk from the collaborationist Vichy regime.

A Netflix series about his life and work is to be released early next year.

Three-quarters of the people he helped were Jewish and they included many artists and intellectuals deemed subversive or ‘decadent’ by the Nazis, as well as 300 British soldiers.

Artists Marc Chagall, Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp were among those who found refuge in a large house used by the ‘Fry Committee’, the Villa Air-Bel in the east of the city.

Writer André Breton also lived there for a time, with wife Jacqueline Lamba and their daughter Aube. Others who were helped included German writer Hannah Arendt and French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss.

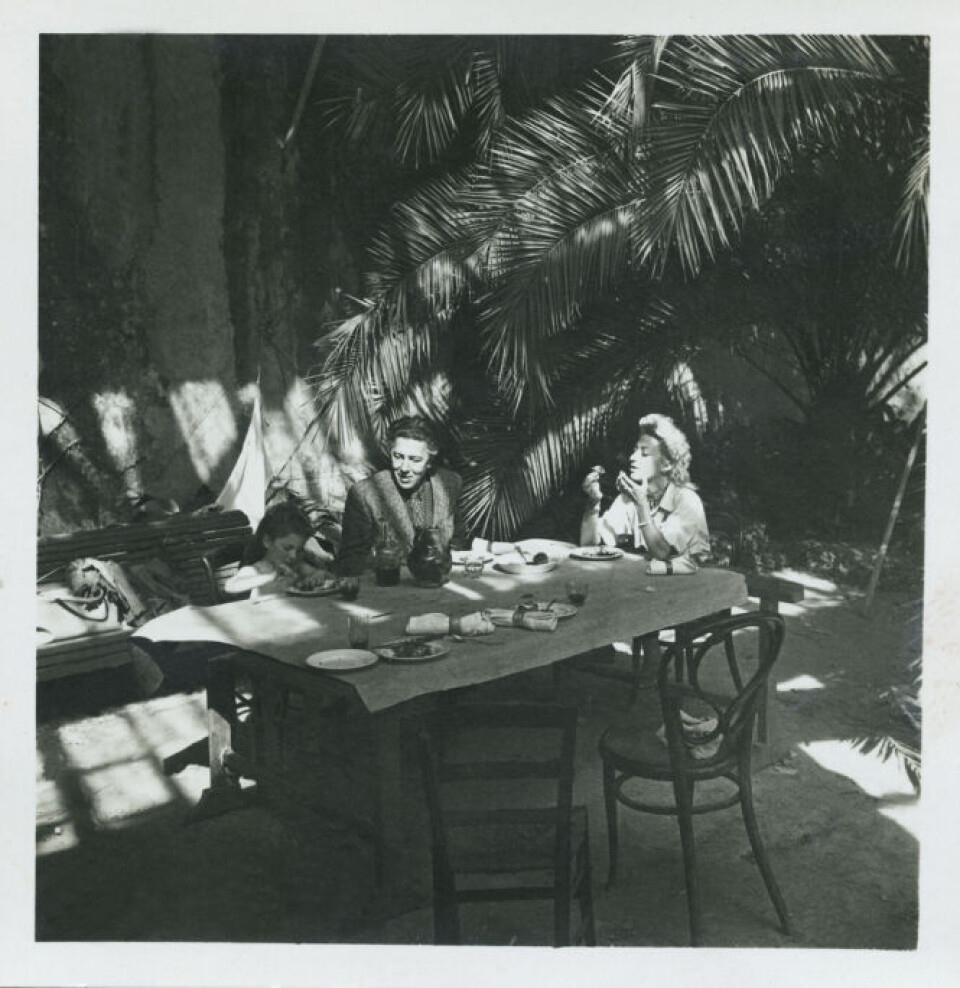

André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba et Aube Breton en 1941 dans la serre de la Villa Air Bel, à Marseille / Archives Pierre UNGEMACH – Droits réservés

Read more: Teacher uncovers wartime heroism to save Jews in France

Artists and intellectuals at risk

Mr Fry arrived in Marseille in 1940 with a list of some 200 artists feared at risk, on behalf of an Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC) supported by wealthy Americans including first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and socialite art collector Peggy Guggenheim.

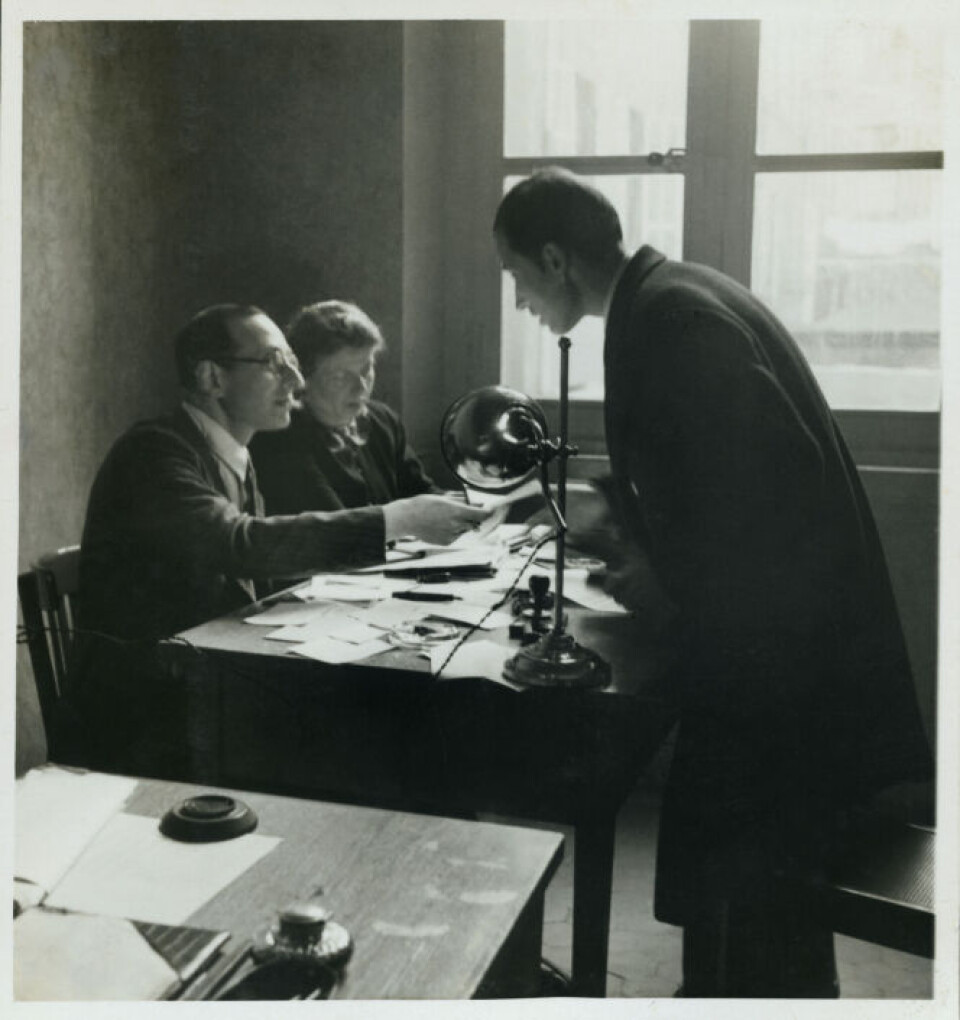

The idea was to help artists and intellectuals obtain visas to the US, but Mr Fry went beyond the remit he was given, mixing legal and illegal activities, and staying until he was expelled by the Vichy police in 1941. Marseille historian Jean-Michel Guiraud, president of Association Varian Fry France, said Fry’s initial mission was to stay a fortnight and assess the situation for German artists and intellectuals in Provence.

“He disobeyed and stayed on and created what he called the American rescue centre, with his right-hand man Daniel Bénédite.

Varian Fry et Daniel Bénédite en 1941 dans les bureaux du Centre Américain de Secours 18, Bd Garibaldi à Marseille / Archives Pierre UNGEMACH - Droits réservés

“When Varian Fry was in difficulty and police wanted to expel him in 1941, the US Embassy approved it as America hadn’t yet joined the war, and even the ERC expressed reserves about his work.”

‘The disrespect for human dignity struck him’

Fry had witnessed a pogrom against the Jews in Germany while working there as a foreign correspondent for a US magazine in 1935.

“He saw a Nazi stabbing a Jew’s hand against a table,” Mr Guiraud said.

“The disrespect for human dignity struck him. He was a humanist: he wasn’t political, he helped people from all walks of life.”

At the time, Marseille was part of the ‘free zone’ run by the Vichy puppet regime, as opposed to the occupied north. “It passed by word of mouth that there was an American in Marseille who could help refugees escape to America or Mexico. They used to fake papers for them – ID cards and ‘authorisations to leave the territory’. There were several networks.

“The first was via the Pyrenees and through Spain on to ships in then neutral Portugal [where Fry had contacts with American Unitarians].

“Another was on boats from Marseille via Gibraltar to French overseas territories such as Martinique.”

Fry was helped by others, including American heiress Mary Jayne Gold or US vice-consul Hiram Bingham IV.

Read more: 80 years ago: Horrors of France’s concentration camp

Read more: In photos: Jewish museum shares moving images of 1941 round up

Read more: Newly surfaced photos show wartime mass arrest of Jews in France

No recognition

He received no recognition on return to the US in 1941, though France gave him the Légion d’honneur in 1967, shortly before he died, aged 59.

He was the first American recognised as ‘Righteous among the nations’ by Israel, in 1994, and was given ‘commemorative’ Israeli citizenship in 1998 and a posthumous medal by the US Holocaust Memorial Council in 1991.

Though he is still relatively unknown, the Association Varian Fry France has been working to preserve his memory since 1999 and has cautiously welcomed the Netflix series, Transatlantic. Scenes have been filmed in Marseille.

However, Mr Giraud thinks it might not focus sufficiently on Mr Fry’s heroic actions. It is expected to include speculative elements, such as a gay relationship, from a historical novel about Mr Fry, The Flight Portfolio.

“I saw some of the filming at the old Hôtel Splendide, where Fry lived when he arrived. They’ve repainted it and done a good job in the historical reconstruction, the costumes and the actors, but we have reserves about the scenario. It’s inspired by a fictionalised story which is surely far from reality.

“I had contact with [writer] Stéphane Hessel [Fry’s alleged lover], who said he didn’t remember that, and it seems unlikely he would have forgotten. I think their relationship was a pretty platonic one.

Concerns over making money rather than paying homage

“We are worried there might be more concern to make money than to pay homage to Varian Fry, but it’s good if it is making more people take notice of his story and work.”

Mr Guiraud said he became interested in Mr Fry after his supervisor for a masters thesis suggested he look into why so many artists and writers had passed through Marseille during the war. He made contact with people such as the former director of the Cahiers du Sud literary journal, which had published pieces by some of them.

“I wondered why all these surrealist writers had taken refuge in Marseille, and had gone to the Villa Air-Bel and grouped around Varian Fry. No one knew who he was back then.

“What had sparked everything off was article 19 [of the armistice signed by Vichy, which promised to hand over on request any German citizens designated by the Third Reich].

Censorship

“That concerned artists and intellectuals of German origin, and Max Ernst fell under that. But the surrealists, and modern art in general, were condemned because it was considered degenerate art.”

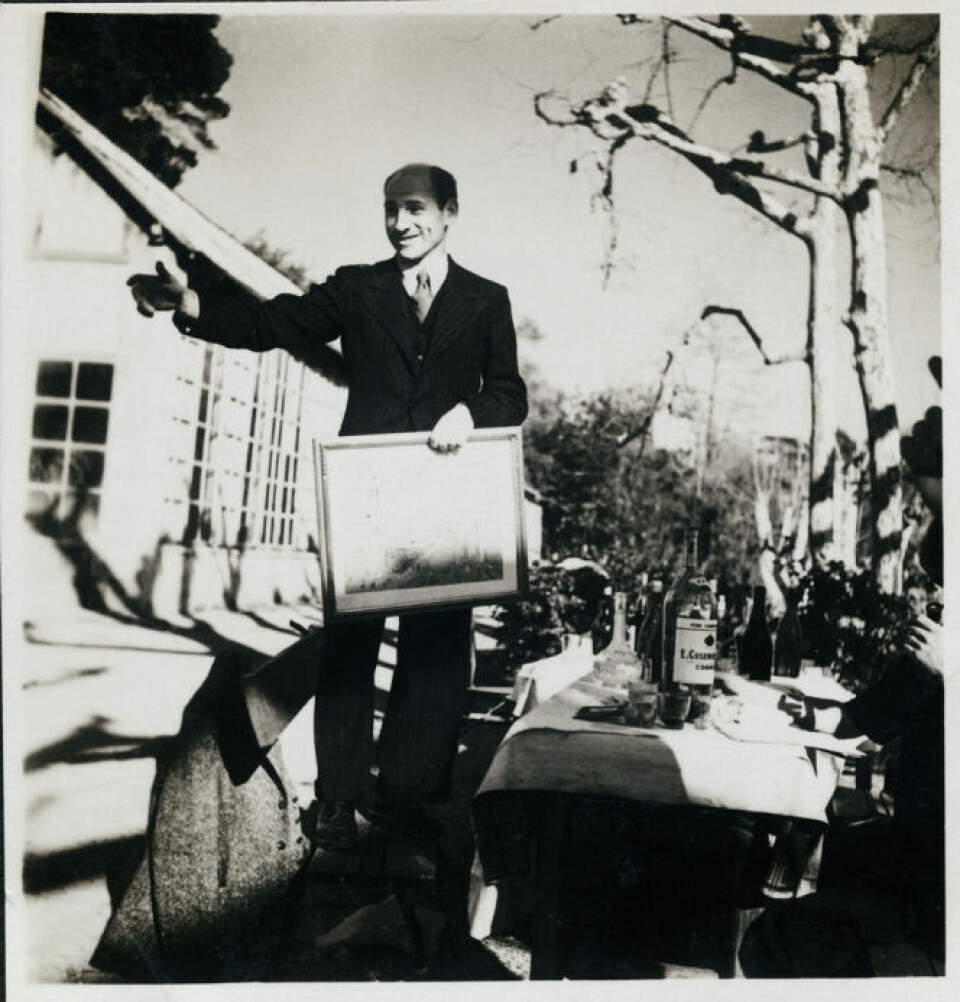

They were subject to censorship by the Vichy regime and galleries refused to show their paintings, he said. “They couldn’t make a living. Sometimes there were auctions organised in Marseille for them – in one photo you see Daniel Bénédite hanging Max Ernst paintings from trees.

“On one occasion, there was a raid of the Villa Air-Bel with several people, including Breton and the Fry Committee team, being held on a boat a few days when Pétain was set to visit.

“They were suspected of being liable to attack the Blue Train as he arrived, because it passed near the house.”

He added: “We understand Fry saved Chagall’s life. He had been arrested in a raid on Jews in Marseille and Fry called the police and told them he was one of the world’s greatest artists and there would be a scandal if they didn’t let him go – which they did. Chagall joined surrealists fleeing to New York.”

Unionists and political opponents of the regime were also among those Mr Fry helped, as well as British soldiers. “

After Dunkirk, they joined French soldiers heading south, thinking they could leave from there, but they got stuck in the region of Marseille.

‘Fry was always smiling and joking – he was very lively’

Piere Ungemach, 84, is the son of Fry’s ‘right-hand man’ Daniel Bénédite and still remembers the war days with Varian Fry.

He said his father, who had strong left-wing views, had been working at the préfecture de police in Paris before the occupation, then went south with Mr Ungemach’s mother and grandmother.

“My father met Varian Fry after he moved to Marseille, and they collaborated together. He was Fry’s ‘number two’ and took care of administration and relations with French officials.

“I remember we spent time at Villa Air-Bel and I was very friendly with Aube Breton. She was my best friend, even though she was older than me.”

His father closed down the Fry Committee office after Mr Fry was expelled and went on to other clandestine activities with the Maquis.

Mr Ungemach said he spent time as a child with relatives in the US, where they met up briefly with Mr Fry at his New York home.

He was there when his parents phoned with news of his sister Caroline’s birth. “I remember he announced to me that I had a sister and I replied ‘I would have preferred a giraffe!’ – though I changed my mind afterwards.

“I saw him again in the 1960s when he came to the south of France and was living in the former home of Chagall. He was a very nice chap, always smiling and joking, very lively and enthusiastic.”

He added: “When I saw Villa AirBel a few years ago, it had been turned into a retirement home. It was a bit sad. It wasn’t what it was – life was fantastic there, with those well-known people and a lot of activity. But I don’t remember it well – I was playing with Aube.”

After his father’s death in 1990, he found a lot of correspondence between him and Fry. “It was all ordered by year. They had maintained close ties for life,” he said.

“To Fry, what he did was a duty and he was proud of it. He did his best and the committee saved a lot of lives and he received good help from his collaborators, including my father.

“Then, after that intense life, he returned to the States where he was totally ignored, and worked as a teacher, living an ordinary life after an extraordinary one.”

Another descendant of Fry’s collaborators, Catherine Hénon, 81, is the daughter of Sylvain Itkine, an actor and director who was protected by the Fry Committee and who later joined the Resistance, being caught and killed by the Gestapo in 1944.

Mr Itkine lived in Marseille from 1940-42 and is known for founding a workers’ cooperative, CroqueFruits, which employed Jewish people and others at risk from the collaborationist regime, making a fruit-based snack.

Ms Hénon said: “He created the co-op with his brother Lucien to give work to the intellectuals, especially foreigners and Jewish people, who were fleeing the occupied zone and wanted visas to leave France.

“It was in that context that he ended up working with Varian Fry.

“He was close to the surrealist artists who were under threat. They worked four hours a day. The rest of the time they could devote to their written and musical work and painting, etc. The Countess Pastré let them live in a chateau.”

She added: “According to family legend, he used his acting skills to get into the Gestapo offices, disguised as a German soldier, to read the lists of people that they planned to catch in raids, and warn them of it.

Daring rescue

Actress Sonia Masson, 48, from Paris, told of her father Diego’s rescue by Fry, when he was helped to get across to Martinique and then America, with Diego, six, his brother, five, and his mother Rose. Diego’s father, André, was an artist and his mother and Diego were Jewish.

They later lived in Connecticut.

She said: “He couldn’t leave via Portugal, because he had drawn caricatures against Franco and would have been in danger in Spain.

“With help of the Fry Committee they left with the last boat, that was called the Carimare, after one that took André Breton and others, in March 1941.

“The Fry Committee helped with the paperwork and to obtain their crossing on the ship. In the period at Marseille they lived in a little gamekeeper’s house on the estate of Countess Pastré. My grandfather couldn’t paint but he was getting financial help from the American rescue centre that helped him to make ends meet.”

She said: “For my father the crossing was exciting. My grandfather had a single cabin, and my father and uncle and mother were in the hold where some accommodation had been fitted out for them, but near to machinery, with no windows, and the rolling movement off the ship – my grandmother was ill all day long and my father and uncle were free to explore the ship.

He is very important to us

“Food was in short supply, but my father said as he was a little kid and didn’t like to eat anyway, it was fine for him. It was all an adventure to him.”

The family returned to France after the war and in later life he had realised the great debt they had owed to Fry.

“He had the impression that his parents hadn’t been grateful enough to him – hadn’t written to him, or maintained any links, even though he’d saved their lives. He felt a bit ashamed of it.

“In the 1980s someone called our family about a documentary on Fry, and he leapt at the chance to take part. He felt that he was able to at least help him be more talked about. It’s been something very important to him, and I also did a live reading in an art gallery devoted to Fry, with extracts from his writings and those who worked with him. He is very important to us.”

Related links

Retired French soldier hunts down war grave thieves and Nazi relics

British team leads dig to recover WW2 US airmen in tiny French village

Painful and important history of France’s World War Two bunkers