-

Letters: The reality of finding a new doctor or dentist in France

Finding a replacement is nigh impossible, says Connexion reader in Lot-et-Garonne

-

The magic of mayonnaise: Why a homemade emulsion always woos guests in France

Plus, which shop-bought mayo brand is best?

-

Learning French: Have you ever dreamt in your target language?

From passive listening to active speaking, dreaming in French can indicate you are regularly practicing it

Comment: Why French institutions must stop their daft use of franglais

The only British member of the Académie française gives us some examples he finds confusing and some he finds pointless

Franco-British Académie française member, Sir Michael Edwards, says he fully supports the body’s new report on the over-use of English by French institutions – and he helped to write it.

In fact, he has been involved in all of the Académie’s committees and reports on excessive anglicisms since he was appointed in 2013.

“I feel it is an advantage that I am a very English Englishman, who writes poems in English but nevertheless understands perfectly the French disquiet at the uncontrollable invasion of English terms. I think it is important to the Académie,” he told The Connexion.

English terms used at the highest levels

The body’s latest report criticises anglicisms in communication – especially on websites – at the highest levels, from major firms to city councils, ministries and universities.

Examples range from the straightforward – a French agriculture campaign called TasteFrance and an association called La French Tech in the Alps – to the less obvious.

These include Sarthe Me Up (the department’s way of promoting itself to entrepreneurs), Bleisure à Lille (leisure opportunities for visiting businesspeople), or Peugeot’s slogan about its excitingly modern cars: Unboring the Future.

Franglais reaching ‘critical point’

Académie secretary Hélène Carrère d’Encausse said the report showed a “critical point” and warned the situation might become irreversible if nothing is done.

Far-right presidential candidate Marine le Pen latched on to it, saying she would ban advertising and communication in foreign languages.

Asked if he agrees with Mrs Carrère d’Encausse, Sir Michael said he cannot predict whether the future is really “as grim as it looks”, but it is “probably good to be alarmist” at this stage.

“People involved in what we have called institutional communication are more and more inclined to use English words or English mixed with French, such as puns between languages.

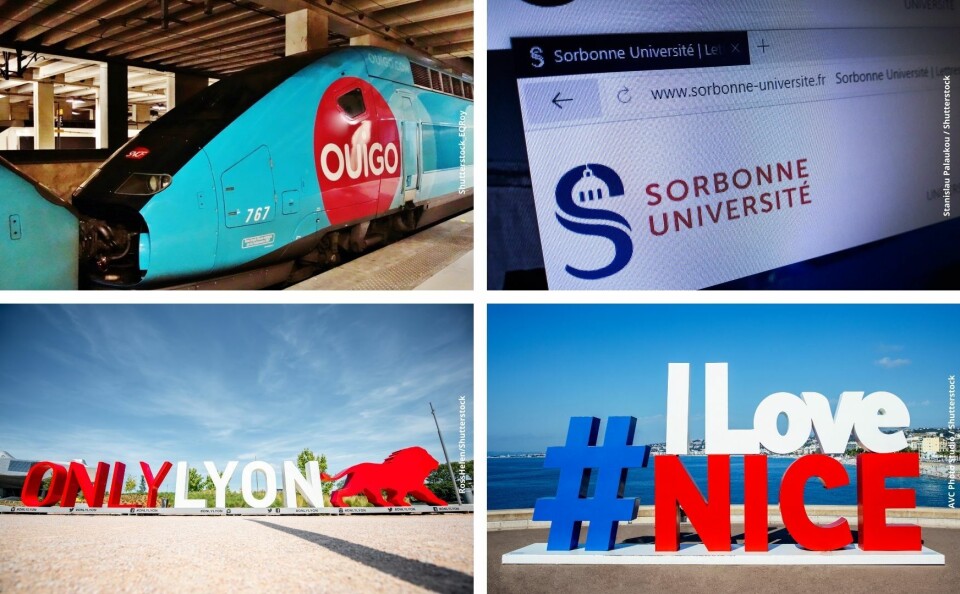

“One could foretell this will continue to encourage the French to use more English words. We are talking about schools and universities, well-known firms, ministries and cities. Only Lyon is now the slogan for the city of Lyon, for example. Others include Smile in Reims and I Love Nice.

Institutions are increasingly behaving like the advertising industry, he said: “Slogans and catchphrases… a kind of downscaling of communication in areas where you would expect a good use of language.”

Some Franglais is elitist

The report says language borrowing has always existed but it is now so prevalent that it is hard for French to properly assimilate the new words.

“Everyone agrees borrowing can be an enrichment, but normally it is step by step. Now it seems uncontrollable, unless those in responsible positions do something,” Sir Michael said.

Some examples actually harm communication, or create elitism, because only those with good language skills understand them, says the report.

“It is excluding people without fairly advanced English and who are not used to passing from one language to another,” Sir Michael said.

“And a lot of examples are hard to understand. We have no idea why CY Cergy Paris Université has ‘CY’ in its name, but assume it is meant to be said in English – ‘See why’.

Read more Franglais ou Frenglish? The history of French resistance to English

Read more Don’t say podcast or clickbait in French say…

Even English speakers are confused

Sir Michael continued, “And there are seemingly English words that even English speakers will not understand, such as Saikle [a bike restoration scheme] that has to be said in English as ‘cycle’, but it is foolish as French people would say ‘sekl’.

Another one is Izy Thalys [a train service] that you are supposed to realise is said like the English word ‘easy’.

“This kind of thing is fine in a bande dessinée, but not in serious communication. In fact, looking at all the examples we found, the overall effect is rather like a comic book.”

Confusion in spelling and grammar is also being caused, the report says.

“There are English words used which ought to be in the plural in French, but are not.

And then there is word order, such as the fact the Sorbonne is now called Sorbonne Université.”

The expression ‘QR code’ is another example of this.

French institutions should use French words

Sometimes English words are used for no apparent reason, such as French universities advertising ‘junior fellowship’ posts, he said.

“It is disquieting to see, not so much that these French people use English, but that they are reluctant to use French whenever they are communicating.

“The communications are not all directed at foreign tourists or students – many are directed at the French. The SNCF trains Ouigo, for example, are not just for foreign passengers.

“We are talking about written communication by important institutions and I do not see why they need to use English rather than French.

“Take Lorraine Airport – I cannot see that any foreigner arriving there would have a problem understanding Aéroport de Lorraine.”

Although they are not mentioned in the report, Sir Michael said he shared the Académie’s concerns about new French ID cards – “something that is all about French identity” – featuring English translation.

He feels confident that government departments will listen to the Académie’s arguments, though he is less sure about companies or cities.

“For now, it is a question of raising awareness and if it is discussed, we hope people will come to their senses.”

What ‘franglais’ have you seen recently and what do you think?

Tell us at news@connexionfrance.com

- Sir Michael has a new book out of essays on Shakespeare, La folie Shakespeare (Presse Universitaire de France).