-

Britons are the largest foreign community of second-home owners in Nouvelle Aquitaine

See which other departments in the region are popular with British nationals

-

Travellers risk extra costs under new Eurotunnel ticket rule

Some fare options are less flexible and less forgiving of lateness

-

May will be difficult month for train travel in France, warns minister

Two major train unions are threatening to strike and are ‘not willing to negotiate’, he says

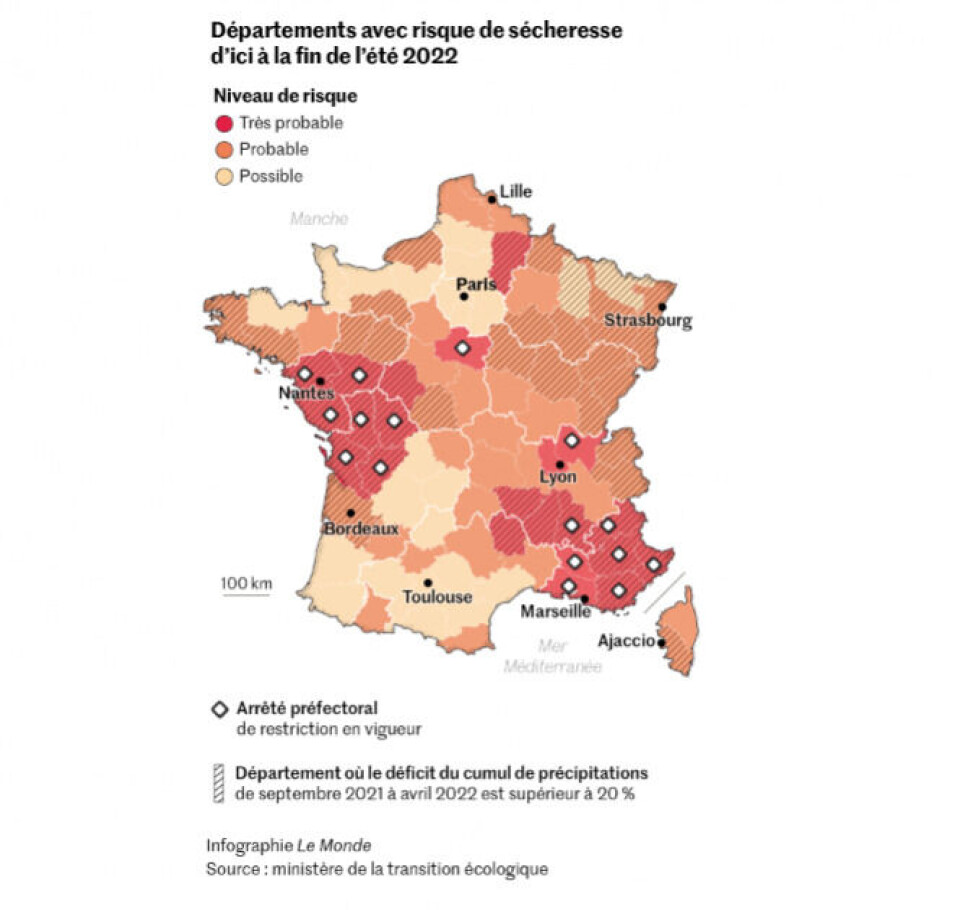

Almost everywhere in France set to be hit by drought this summer

A new map shows just how high the risk is. Climate experts predict a ‘water war’

Almost all of France is set to be affected by drought this summer, with the southeast and western areas especially impacted, new data shows.

The Ecology Ministry and Le Monde have published a map showing the risk level of drought this summer across the country. The risk is classified from “possible” (the lowest level) to “very probable” (the highest level).

No area in France is without drought risk.

Read more: Water restrictions in place: how bad is the drought risk in France?

A total of 76 zones are currently on alert for low water levels, and 26 on high alert. This compares to six and two on the same date in 2021.

In addition, 16 departments have no fewer than 51 prefectural decrees in force to limit water usage. These are especially in force in areas where the deficit of rainfall water from September 2021 to April 2022 was more than 20%.

In 2011, a government website was introduced that allows users the chance to find out about the drought risk in their area, and if any water restrictions have been imposed.

The map specifically shows 22 departments at “very probable” risk of drought before the end of the summer.

Credit: Screenshot / Le Monde / Ecology Ministry

The map uses a range of data to compile its assessment, including a lack of rainfall, water table levels in underground reservoirs, the moisture level of the ground, and dropping levels of rivers and lakes reported by local biodiversity agents at l’Office français de la biodiversité.

Groundwater underground makes up two-thirds of the water we later use to drink, and one-third of the water used in agriculture, and it is usually replenished in winter due to rainfall.

However, there was relatively low rainfall in the autumn of 2021 and winter of 2022. Levels were especially low (lower than 100ml) from Vienne to Maine-et-Loire and Indre-et-Loire, and especially in the Alsace area (less than 50ml).

Simon Mittelberger, climatologist at Météo-France, told Le Monde: “Some areas are in a critical situation. We are seeing very dry to extremely dry ground.”

He added that since January 1, the absence of rain has caused deficits of up to 20% compared to the averages recorded over 1981-2020.

In January, the lack of rain reached a deficit of 45% in the former Poitou-Charentes region, and reached over 50% from Vendée to Charente-Maritime, as well as in the west of Brittany, Hauts-de-France, and Ardennes; and from the Massif central to the Rhône Valley.

The Côte d’Azur and Provence region have also been badly affected as has the Pyrénées region.

Mr Mittelberger said that while it will probably “be warmer and drier than normal in the southern half of the country, we don’t have a clear trend for the northern half”.

Hydro-geographic monitoring agency Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM) predicts that climate change could slow this replenishing over winter via rainfall by 10-30% by 2070.

38 days of higher-than-normal temperatures

The publication of the map comes as the country experiences a record-breaking 38 consecutive days where temperatures are above seasonal norms.

Weather services are predicting this series to continue, with hot weather expected until at least this weekend.

Since the beginning of April, the average temperature has been three degrees celsius more than usual, Météo-France reports.

The weather service has said that it is “highly likely” May 2022 will be the hottest May in the post-World War Two period.

‘A water war is arriving in France’

Concern is growing across the country about the growing drought risk. On May 16, 15 associations filed an appeal against water development and management plans in the Adour-Garonne basin. They argued that the current plan allocates too much water for agriculture to the detriment of the environment.

National fishing group la Fédération nationale de la pêche en France, which has 1.5 million members, also launched a campaign on May 18 to “save our rivers”, which it says are so badly treated that some fish species are struggling to survive.

Emma Haziza, a water expert who has created a team of experts on climate risk, said that “a water war is arriving in France”.

She said: “We must stop draining, deforestation, restoring wetlands, and watering cities and roads. We must 'de-accelerate' the great water cycle, give it time to infiltrate, and take this resource into better consideration.”

She warned that when 40% of water or more is taken, for use in agriculture for example, the ground “becomes arid”. She added that “large reservoirs are subject to evaporation, which becomes more intense as temperatures rise”.

Ways to ‘restock’ water

While the water table often struggles to refresh itself naturally during the winter, some have been developing a system to ‘restock’ it artificially, by storing water accumulated during the winter more efficiently, so it can be re-used over the summer.

The technique was first developed in the late 1950s and early 60s, but is still only used at around 20 sites in France. The country’s oldest such site is located in Le Pecq, near Paris, which uses water from the Seine.

It seeks to speed up the replenishment of the water table, by capturing water that falls during the winter (cleaning it of waste first). Every year, this enables 15 million-20 million metric cubes of water to be pumped from the Seine and stocked (the equivalent of 40,000 Olympic swimming pools).

The water is then cleaned and naturally filtered, and sits in large basins for a couple of days before being pumped into filtration centres to ensure it is in perfect drinking condition.

This water is then pumped into the water table. It takes around 22-23 days to get safe drinking water after it is taken from the Seine, and the amount produced is enough to supply one million people.

The system therefore allows water to be stored and cleaned, and returned to use, without relying on the naturally-replenished underground water table.

However, it has its limits. It requires an available water source (in this case, the Seine), and a geographical area that allows the water stockage plant to be built and function well.

Related articles

Climate change in France: People 'do not understand what's coming'