-

Trump calls for Marine Le Pen to be freed (but she is not in prison)

US president said her embezzlement court case was a ‘witch hunt’

-

France’s €3 book delivery fee challenged in EU court by Amazon

Online retailer said measure is protectionist and ‘in breach of EU laws’

-

Allergies: How to know pollen levels in your commune of France

Interactive online maps can track and predict how pollen is changing in the air

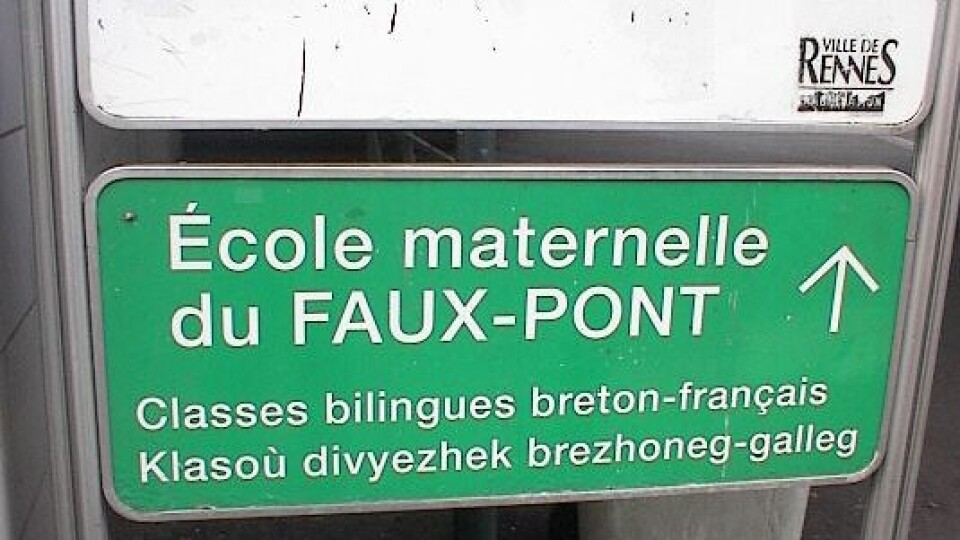

France adopts historic law to protect its regional languages

It opens up the possibility of teaching in schools being carried out in regional languages for the majority of the school day

France approved yesterday (April 8) a new law aimed at protecting and promoting regional languages across the country. It is the first new law related to regional languages since the creation of the French Fifth Republic in 1958.

It concerns all regional languages in the country including Picard, Breton, Corsican, Alsatian, Flemish, Basque, Occitan, Creole, etc.

It will give primary schools the possibility of “immersive teaching” in a regional language, meaning they can offer teaching in a specific regional language for the majority of the school day.

The French language would be introduced gradually until the pupils are completely bilingual by the end of primary school.

The law also proposes the “generalisation” of learning regional languages in schools at all levels, from nursery to high school.

It is a different option to the current systems in bilingual, international schools or Diwan schools, which are schools where education is provided in the Breton language.

Another element of the law states that local authorities will need to provide a financial contribution to pupils who wish to be educated in a regional language when it is not possible to do so in the commune where the pupils live.

🔵 C'est historique ! L'Assemblée nationale vient de voter "conforme" la proposition de loi de @Paul_Molac et devient donc la première loi sur les #languesrégionales de la Vème République 👏👏 Le @GroupeLibTerrAN est fier de cette grande victoire #DirectAN pic.twitter.com/fHPzdPem7U

— Groupe LIOT (@GroupeLIOT_An) April 8, 2021

The bill was backed by a majority of MPs at the Assemblée nationale - 247 for, 76 against and 19 abstentions, having already passed through the senate.

Paul Molac, the MP for Morbihan in Brittany and the author of the bill, welcomed the vote.

“It is historic: for the first time in the history of the Fifth Republic, a law on regional languages has been passed,” he Tweeted after the decision.

“The dedication of associations, local elected representatives and the tenacity of parliamentarians has paid off. This is a great day for our languages.”

Régions de France, an institution representing the French regions to the French public authorities and European institutions, also welcomed the new law.

“The Regions, which are responsible for preserving and promoting regional languages, will now ensure the implementation of this historic law on the ground, particularly in secondary schools,” it wrote in a press release.

“We [Régions de France] are at the disposal of state services, municipalities and departments, associations and educational communities to carry out this mission. There is an urgent need to protect our regional languages, which are in great danger of extinction!”

Despite the law receiving majority support, it was not backed by President Emmanuel Macron’s party La République En Marche! or Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer.

Bastien Lachaud, MP for left-wing political party La France Insoumise, criticised the bill and those supporting it during the parliamentary debate.

“You have voted for decreasing education budgets, you have decreased the resources for education, you have decreased the number of teachers…

“So to say today that we're going to do immersion without giving the means to the national education system to do it is more wishful thinking.”

After the vote, Mr Molac and his colleagues from Brittany gathered on the steps of Palais Bourbon, where the Assemblée nationale gathers, to sing a rendition of Brittany’s anthem Bro Gozh ma Zadoù (old country of my ancestors).

Après le vote d'une loi sur les #languesregionales , quoi de mieux qu'un Bro Gozh avec les collègues bretons ! pic.twitter.com/1zvSs7HaHS

— Paul Molac (@Paul_Molac) April 8, 2021

There is no up-to-date or exact data on how many speakers of regional languages there are in France.

A study carried out by the Institut national d'études démographiques in 1999 found there to be nearly two million speakers of Creole and Berber languages, 548,000 speakers of Alsatian, 526,000 speakers of Occitan, and 304,000 speakers of Breton.

Read more:

Law bans accent discrimination in France

The grim origins of French PM's "sorti de l'auberge" phrase