-

French second-home visa issues raised in House of Lords

British people experience an "expensive and bureaucratic process" to continue living in France

-

More than 5,000 French communes use AI to identify poor rubbish sorting

Badly-sorted rubbish can cost millions so communes are turning to high-tech solutions

-

Tax on well-off retirees under consideration for 2026 budget

‘Nothing is off the table’ when it comes to finding €40 billion in savings says Labour Minister

French sailors’ love letters in UK reveal messages 265 years on

The letters, which were never read by their intended recipients, offer rare insights into ‘normal’ 18th century people in France

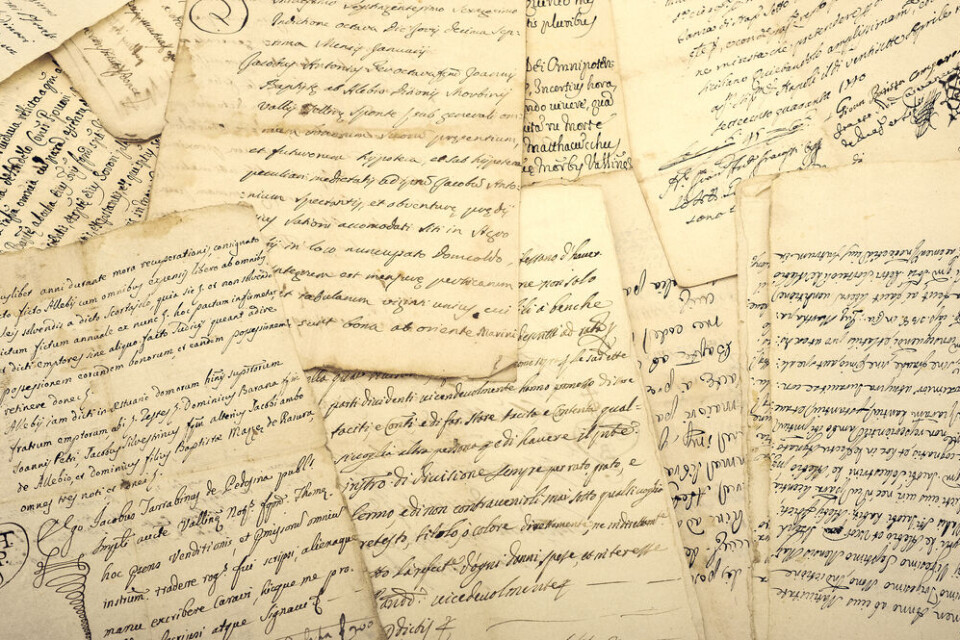

Heart-breaking letters sent by French families to sailors in England more than 265 years ago have been opened and published, and hailed as important historical documents evocating “universal human experiences”.

The 104 letters were intercepted by the Royal Navy during the years 1756 and 1763, during the Seven Years War between Britain and France over their colonial holdings. They never reached their intended recipients, and are only now being read.

"18th Century POW love letters opened at last by Cambridge professor".

The headline might be a bit OTT but this discovery by Renaud Morieux, is very exciting! 104 letters written to captured French sailors, many by the women left "holding the fort". https://t.co/hxzgrBLfp3 pic.twitter.com/GAXqPNyjDF— Dr Elizabeth McDonald (@DrPastonsRUs) November 7, 2023

59% from women

They include a love letter to an officer from his wife, and a missive from a mother asking why her son does not write more often. More than half (59%) are written by women to their husbands, fiancés, brothers, and sons.

Excerpts include:

-

“I would spend the night writing to you…[from] your faithful wife for life. Good evening my dear friend. It is midnight. I think it's time for me to rest,” from Marie Dubosc in 1758, to her husband Louis Chambrelan, first lieutenant on the French frigate Galatée, which was captured by the British. Marie would die a year later.

-

"I think more of you than you do of me…finally, I wish you a happy new year filled with the Lord's blessings,” from Marguerite Lemoyne, mother of Normandy sailor Nicolas Quesnel, on January 27, 1758.

The Galatée had been bound for Louisbourg, Nouvelle-France (modern-day Canada) from Bordeaux, and had been part of a 40-ship fleet aiming to lift the British blockade.

However, the ship was captured in the Atlantic by the British ship the Essex, and taken first to Plymouth, and finally to Portsmouth, in the UK. The letters went with it.

The letters were later transferred to the British National Archives, in Kew, south-west London, and had been considered as military documents.

They laid in a box, all-but-forgotten, until they caught the attention of Professor Renaud Morieux, Professor of History at Cambridge University.

As part of his 15-year work, Professor Morieux identified each of the 181 members of the Galatée frigate, and also completed genealogical research on the sailors and writers. A quarter of the crew had been sent a letter.

Yet, the notes were never sent to their intended recipients, said Professor Morieux. This was not as a result of wartime censorship or intentional cruelty, he said, but most likely due to a lack of Royal Navy resources to deliver them to captured sailors across the UK.

The historian’s findings have now been published today (Tuesday, November 7) in the journal Les Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales.

“I realised that I was the first person to read these very personal messages,” he said, after finding the letters grouped in three piles and held together by ribbons. “Their recipients weren't so lucky. It was very moving.”

In 1758, around 60,000 French soldiers were involved in the war, and a third of them were captured by the British Navy. Over the entire Seven Years War, 65,000 were detained. Some died of disease and malnutrition, while others were eventually released.

The war was eventually won by the British-Prussian alliance.

‘Normal’ writing and universal experiences

The letters are some of the only documents to show writing between more ‘normal’ people at the time, in contrast to the typical literature and letters from the period, which tend to have been written by high-profile aristocratic, royal court, and Enlightenment figures, said the professor.

They also show the everyday lives of those left at home, and the ways in which they paid rent and managed their households in the absence of their male relatives. In this way, the war was seen as a conduit to greater female autonomy.

Yet, some of the ‘writers’ and recipients may also have been illiterate, so many of the letters may have been dictated to a scribe, and would have needed to be read aloud at the other end.

“Staying in touch [then] was a community effort [but these letters contain] universal human experiences,” said Professor Morieux. “Today, we have Zoom or WhatsApp, but in the 18th century, people only had letters. What they wrote resonates today in a very familiar way.”

Related articles

Five French civil wars - from Charlemagne to the Paris Commune

Filer à l’anglaise: A French expression you may hear today

Did you know: First woman to sail around the globe was French