-

Which fruits, vegetables and fish are in season in France this April?

Strawberry season begins, compensating for end of winter vegetables

-

Why are drivers in France increasingly getting speeding fines without being ‘flashed’?

Here is why you may have received an unexpected fine in the post

-

Marine Le Pen appeal decision should be given in summer 2026, says court

It comes as the RN leader continues to maintain her ‘innocence’ and right-wing politicians have called her conviction ‘an attack on democracy’

Organ donation in France: Why it is good to talk about it

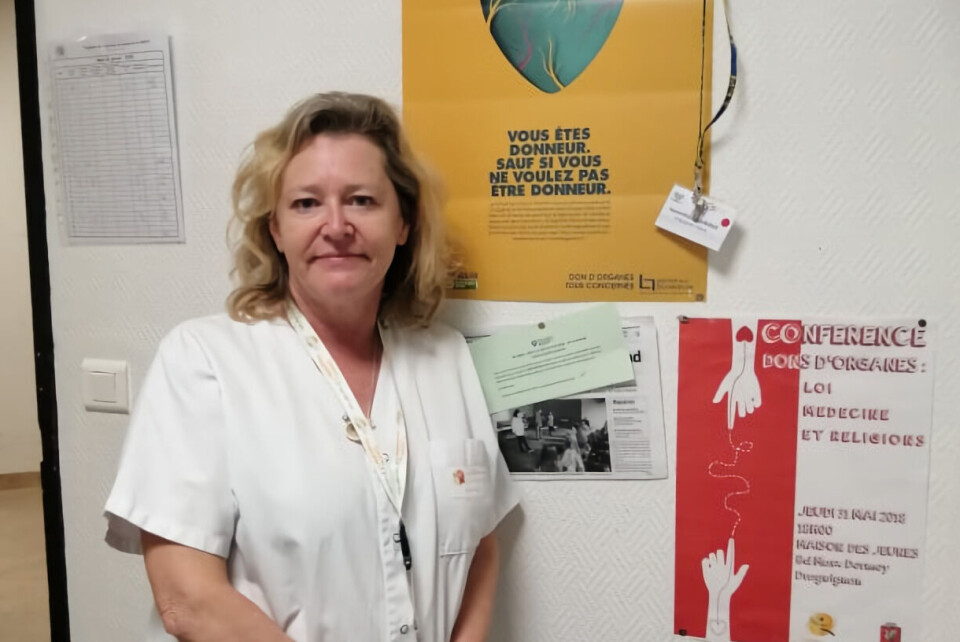

Working as an organ donation coordinator is emotionally gruelling but very rewarding, says Samantha Alexander, an organ transplant coordinator in the southern Var department

France has set out a new €210million organ and tissue donation plan for 2022 - 2026, announced on March 14. The aim is to carry out 40% more transplants by 2026, meaning a total of between 6,760 to 8,530 per year.

To understand how the system in France works, we spoke to organ transplant coordinator Samantha Alexander, who left her job as a nurse in England to move to the Var in the south of France 13 years ago.

She took a job in the intensive care unit (ICU) at the Centre Hospitalier de la Dracénie in Draguignan and later became transplant coordinator, alongside her ICU work.

“It is hard work. When there is an organ donation, I can be at the hospital for 36 to 48 hours. It is stressful and emotional,” she said.

“But the next day when you know that an organ has been transplanted into someone else and they have been saved, it is a great feeling.”

In 2021, 5,273 organ transplants were carried out in France, coming from 1,392 dead donors and 521 living ones. This is an increase of 19.3% compared to 2020, when donations were heavily impacted by the coronavirus pandemic.

“My colleague and I were re-deployed to the ICU for months to cope with the sudden influx of patients so the activity of the coordination team was suspended, operating theatres were closed, and nurse anaesthetists came to ICU to help.

Read more:Can I donate my body to science once I die in France?

“The agency in charge of organising transplants suspended non-urgent kidney transplants and tissue transplants for seven weeks,” Ms Alexander, said.

The pandemic had other impacts.

Periods of national confinement meant fewer road traffic accidents, so fewer donors. In addition, anyone who died testing positive for Covid could not be considered as a donor.

“There are an enormous amount of tests that happen, plus a very close look at the patient’s medical history,” Ms Alexander said.

“But at the other end of that, there is someone waiting desperately for, perhaps, a new heart.” At any one time there are around 26,000 people waiting for an organ donation in France.

Some 900 people each year die because they do not get a transplant.

These are usually people who are in urgent need, such as those who require a transplant within 48 hours, whether it is a heart, lungs, or sometimes a liver, Ms Alexander said.

The main people on the waiting list are those needing kidneys.

When someone dies with organs or tissues that can be useful, Ms Alexander contacts the family.

“We want to find out if the person maybe talked about wanting to donate their organs. We sometimes have three, four, five interviews with them.

“We ask what sort of person their relative was. Were they generous?

“And, of course, we respect the wishes of the person and their family.” France has an ‘opt-out’ system for organ donation, and very few people remove themselves from the list.

However, the percentage of refusals by relatives of the dead is still high, at 33.6%, despite the number of people waiting for transplants.

“As a coordinator, if the person is declared brain dead (for organs) or their heart has stopped (for tissues), I automatically ask their loved ones if they had talked about organ and tissue donation and if the deceased was against it,” Ms Alexander said.

“Some people know the answer but a lot of people have not discussed it and so the family has to make that decision, leading to the high rate of refusal. A phrase I hear all the time is ‘We never talked about it so, just in case, I would say no’.” Ms Alexander said that for anyone who is resident in France, it is extremely important to discuss their thoughts about organ donation with family and loved ones so their wishes are known in case their organs or tissue can be used to save another person’s life.

“Heart and lungs have to be transplanted really quickly, in about four hours,” she said, stressing the urgency that is required in this situation.

Read more:Is France’s blood donation ban on people who were in the UK justified?

She added that anyone could potentially end up providing life-saving or life-changing organs or tissue upon their death, as each organ is assessed individually. Donors have supplied livers and kidneys at 90 years old, or 100 years old for corneas.

“Hearts and lungs usually come from younger patients but each organ is examined minutely,” she said.

Ms Alexander said it was not as difficult as many might suppose to go from working in a hospital in England to one in France.

The big challenge was getting through the language barrier, she said.

“When I moved over, I already spoke French but not much in terms of medical vocabulary. But it was enough to get by in intensive care, and then it got better. The work was basically the same, the doctors the same.

“Everyone is just trying to do their best for the patients who come in.”

She says that her job, for all its challenges, is ultimately rewarding.

“It can be emotionally draining – being in ICU is already draining – but over time you get to think about it as being a gift to somebody else.

“For families who have lost loved ones, when their organs are donated and somebody else gains from that, it can be uplifting.

“When younger people die and they give their organs, it can often be a great comfort for the family, knowing that that person has helped someone else, even after death.”

If you have any questions about organ donation in France, we would be pleased to pass them on to Ms Alexander. Please email news@connexionfrance.com

Related articles

Can British people banned from giving blood in France be organ donors?

Death of a family member in France: Steps to take in days after

France to lift blood donation ban for gay men who have had recent sex