-

White storks make strong return in France via nest ‘platforms’ and clipped wings

The Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux shares the conservation challenges in saving these birds from extinction

-

Hosting scheme in south-west France lets newcomers sample lifestyle

Households in nine Dordogne communes volunteer under Mes Nouveaux Voisins scheme

-

French boulangeries demand right for staff to work on May 1 so they can open

Artisan bakery owners can work but employees cannot, while certain industrial bakeries are allowed to remain open with workers

Macron-Le Pen gap, end of tradition: Six key points of French election

The race to win is not the only story this year, with the future of two traditional parties in the balance, a possible record for the Greens and the fate of outsider Zemmour all to be decided

Campaigning for the first round of the 2022 French presidential election will end tonight at midnight, with the electorate heading to the polls for the first round this Sunday April 10.

The run-up to this year’s election has been heavily impacted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has reshaped the candidates’ strategies.

Far-right candidate Éric Zemmour has lost popularity due to apparent sympathies for Russian leader Vladimir Putin, while his ideological ‘frenemy’, Marine Le Pen, has seemingly gained popularity despite expressing similar sentiments in the past.

Read more:Marine Le Pen: ‘Putin could become ally to France again’

Read more:Former French PM says Le Pen can win, Zemmour makes her look moderate

Incumbent President Emmanuel Macron scored an initial boost due to his handling of the war, but that seems to have dwindled in the past week, according to the polls (see more on this below).

Mr Macron is aiming for a second successive quinquennat (five-year term), a feat that has not been achieved since Jacques Chirac, who served between 1995 and 2007. In fact, Mr Chirac and his predecessor François Mitterrand are the only two French presidents to have served two full terms in office – others, such as Charles de Gaulle, did not complete the full second term.

Read more:Why don’t the French like the presidents they elect?

The narrowing gap between Mr Macron and Ms Le Pen is one key talking point of this election, but not the only one. We highlight six elements you should look out for as results start to come in on Sunday evening/Monday morning.

What will the gap between Macron and Le Pen be?

Mr Macron of La République En Marche and Ms Le Pen, now of Rassemblement National (formerly Front national) faced off in the second round in 2017, with Mr Macron coming out as victor with 66.1% of the vote.

The pair are also favourites to make it to the second round this year, with Ms Le Pen closing in in the polls in recent days.

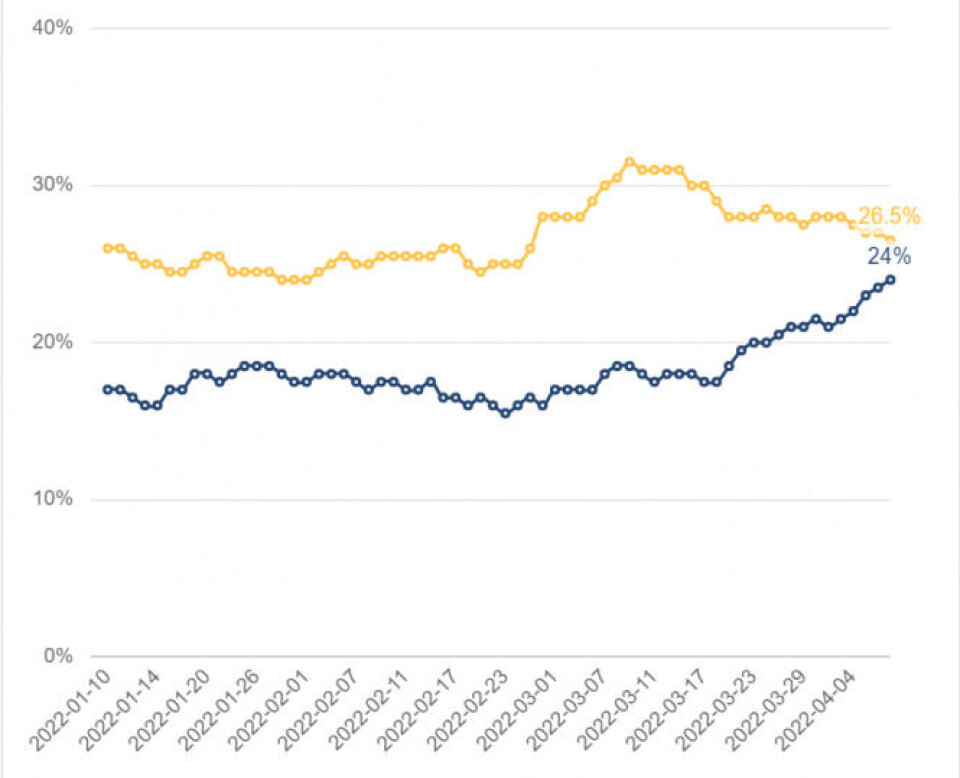

The graph below shows Ifop’s rolling poll of the electorate’s intention to vote in the first round on Sunday. Mr Macron is represented by the yellow line, and Ms Le Pen by the blue line.

Ms Le Pen has slowly but surely eaten away at Mr Macron’s lead, which on March 9 was as much as 13 percentage points. As of April 7, that lead is just 2.5 percentage points.

Pic: Ifop

Mr Macron also only has a very slender lead in the second round too, as shown below.

Pic: Ifop

However, polls can be misleading (they are often wrong) and do not take into account undecided voters, who often play a big role on the day, or people who change their mind at the last-minute.

Will Mélenchon be able to unite a divided Left?

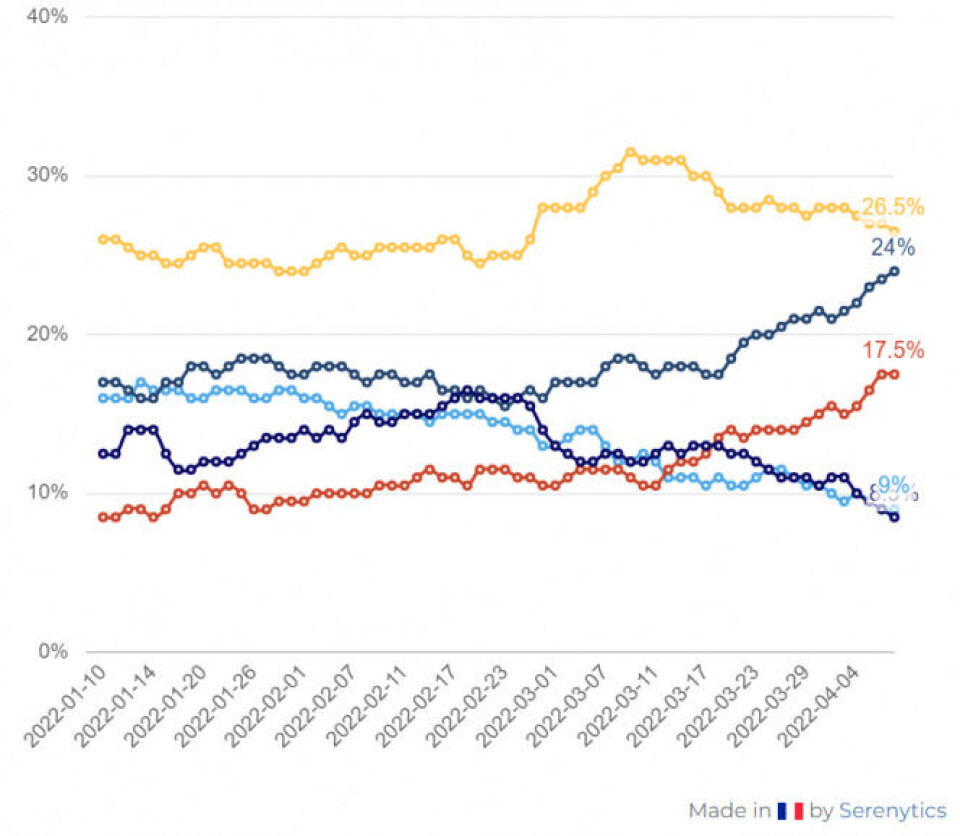

Jean-Luc Mélenchon has slowly but surely been gaining in the polls in recent weeks, and now sits as the third favourite.

In Ifop’s rolling poll, he currently has 17.5% of the intention to vote in the first round.

Below, Mr Macron is yellow, Ms Le Pen is blue, Mr Mélenchon is red, Mr Zemmour is the darkest blue and Valérie Pécresse is light blue.

Pic: Ifop

Antoine Léaument, head of Mr Mélenchon’s digital communication, told BFMTV earlier this week that his candidate is "focused on a single objective: to be in the second round".

In recent elections, France’s left-wing candidates have been MIA from the second round.

The traditional leftist party, Parti socialiste, headed up this year by Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo, is polling so poorly that it could be labelled as one of the most inconsequential players in this election.

Other left-wing candidates are more radical, such as the communists Nathalie Arthaud of Lutte Ouvrière and Philippe Poutou of Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste.

Yannick Jadot of the Greens is doing relatively well considering the Greens’ history in France, but is still an outside shot.

All this means that Mr Mélenchon may sweep up left-leaning voters who decide to go for tactical voting (le vote utile).

The Fondation Jean-Jaurès, a think tank associated with the Parti socialiste, showed in a recent study that Mr Mélenchon benefited from "transfers of votes from the rest of the left, both from the radical left and from leftists who have supported the current administration".

What mark will Zemmour make?

The former political commentator shook up the early stages of the election campaign, and as recently as February 18 this year was polling neck-and-neck with Ms Le Pen, on 16.5%.

His percentages have tailed off in recent weeks, but he is still hoping to make a mark.

At one point he was hoping to win in parts of Paris, but is now focusing more of his attention on the departments Var and Vaucluse in the southeast of the country.

His party - Reconquête - is hoping to form a group in the National Assembly, meaning he will need 15 members of his party to be elected as MPs. This is a “very ambitious goal”, according to BFMTV.

For Mr Zemmour to make a big impact, it is likely he will have to side with other right-leaning politicians, and he has already established several local agreements with members of Les Républicains (LR).

His controversial ally, Marion Maréchal, niece of Ms Le Pen, called for a “grande coalition” of the right, ranging from Reconquête to LR member Eric Ciotti.

His results in this election may be crucial in determining whether he will continue in politics, and build up his party to challenge again in five years’ time.

Will the traditional right implode?

Just like the traditional left, the right-wing Les Républicains have their own issues at this election.

They are represented by Ms Pécresse, who has found herself lost between Mr Macron’s central right policies and Mr Zemmour and Ms Le Pen’s far-right ideas.

Due to that, she is appealing to very few people. She is currently polling as fourth favourite, with 9% intention to vote in the first round, just ahead of Mr Zemmour on 8.5%.

Ms Pécresse’s campaign stalled almost before it started.

She gave a much criticised speech to launch it on February 13, which drew headlines only because she mentioned the fringe conspiracy theory - espoused most notably by Mr Zemmour - labelled the “great replacement”, and because of her bizarre power poses.

It was downhill from there, and she is not expected to be anywhere near qualifying for the second round, which poses questions about the future of the once-strong party.

Read more:‘Why the ‘great replacement’ theory does not make sense in France’

A faint hope for the Greens

Yannick Jadot of the French Greens, called Europe Écologie Les Verts (EÉLV), is polling favourably considering the history of the party, hovering around 4.5% of the intention to vote in the first round.

The Greens in France usually score between 1.3% and 3.8% in the elections. The exception to this was when Noêl Mamère won 5.25% in 2002.

Mr Jadot is not far from being on course to match or even better this.

However, it still represents quite a low score despite the fact that the environment has become one of the key issues of this century, and is crucial to many of the younger generations.

Daniel Boy, a specialist in political ecology in France, said this is down to three factors.

The first is left-leaning voters tactically choosing Mr Mélenchon, the second is the importance this year of purchasing power (with environmental policies usually seen as harming rather than improving households’ income) and thirdly because not enough voters see Green candidates as “credible” to lead the whole country.

“A green mayor is allowed, a green MEP is allowed, but not at the national level, not even at the legislative level,” Mr Boy told BFMTV.

Could this be the swan song of the PS?

The Parti socialiste (PS) has been in turmoil for a number of years now.

In 2017, candidate Benoît Hamon received just 6.36% of the vote.

This year, Ms Hidalgo is polling at just two percent. If she does not win at least five percent of the votes, the State will not reimburse her campaign, which could cause financial difficulties for a party with waning resources.

The party already had to sell its headquarters on the banks of the River Seine in Paris in 2017, moving to the suburbs.

The PS’ downfall has mainly been caused by the rise of Mr Macron’s La République En Marche, which stole members and voters alike.

If PS do only capture a few percent this year, it could be their final reckoning.

Read more:French political parties: What killed off the Left and can it recover?

Read more:Why does ‘left-wing’ France vote for election candidates on the Right?

Abstentions

One final element to look out for is the potential for a high rate of abstentions this year.

The record was set in 2002 when 28.4% did not go to vote in the first round. Some experts are predicting a similar or even greater rate this year due to complacency and disillusionment.

You can read more about this in our article here: “French election: Why Le Pen and Mélenchon risk most from abstentions”

Related stories

French site pairs foreigners who want to vote with election abstainers

Votes, budgets, rules: how the French election works and quirky facts

Which French presidential candidate would you most want to camp with?