-

Know your cheeses and their seasons: which to eat in France in February

Cow’s milk cheeses dominate as winter comes to an end

-

Films and series to watch in February to improve your French

Every month we outline good film and TV series to improve your language

-

Duck Cold! Four French phrases to use when it is freezing outside

France's current cold spell is set to continue for the next few days - we remind you of French expressions to use to describe the drop in temperature

‘Brocantes’ and antique markets - a lucky dip of France's rich history

A chance to stroll through the stalls, pick over the goods and acquire your own piece of French history. Michael Delahaye explains the appeal and how to haggle

One of the many words in French which have no English equivalent is the verb chiner.

Put it into an online translation site and it will come out as ‘to hunt’ or, more mysteriously, ‘to antique’.

Come across it in a whole sentence – On chine dans une brocante – and you get the idea.

Un chineur is a frequenter of brocantes – and I am guilty as charged.

Brocante is something of an umbrella term.

It can include an antiques fair at the top end and, at the other extreme, un marché aux puces, a flea market.

At the same lower level is the vide-grenier (literally, ‘empty your attic’), which equates to the British car boot sale but without the soggy field, leaden sky and sullen sellers.

Wandering around a brocante is one of the great pleasures of living in, or just visiting, France.

Unless you are a collector, the best approach is to think of it not as a bargain hunt with specific items in mind, but a lucky-dip bran tub on the scale of a market square.

It is not about what you are looking for.

It is what you may chance upon.

After all, our word bric-a-brac comes from the French à bric et à brac, meaning ‘at random’.

They are educational too.

Brocantes offer an insight into France’s rich and layered history.

Among the busts and paintings, you will come across the humblest of household items – with all the scuffs, dents and knocks inflicted on them over decades of use and misuse.

Books may give you the dry facts of, say, La Belle Epoque, but brocantes allow you to handle and, if so inclined, acquire objects once belonging to the ordinary folk who lived through such periods.

The range of items is truly astounding, from bronzes to bedpans.

Over the last 30 years of both visiting and living in France, I have acquired a collection of about two dozen items.

Along with Julie Andrews, I can truly say: “These are a few of my favourite things.” Every one of them tells a story:

-

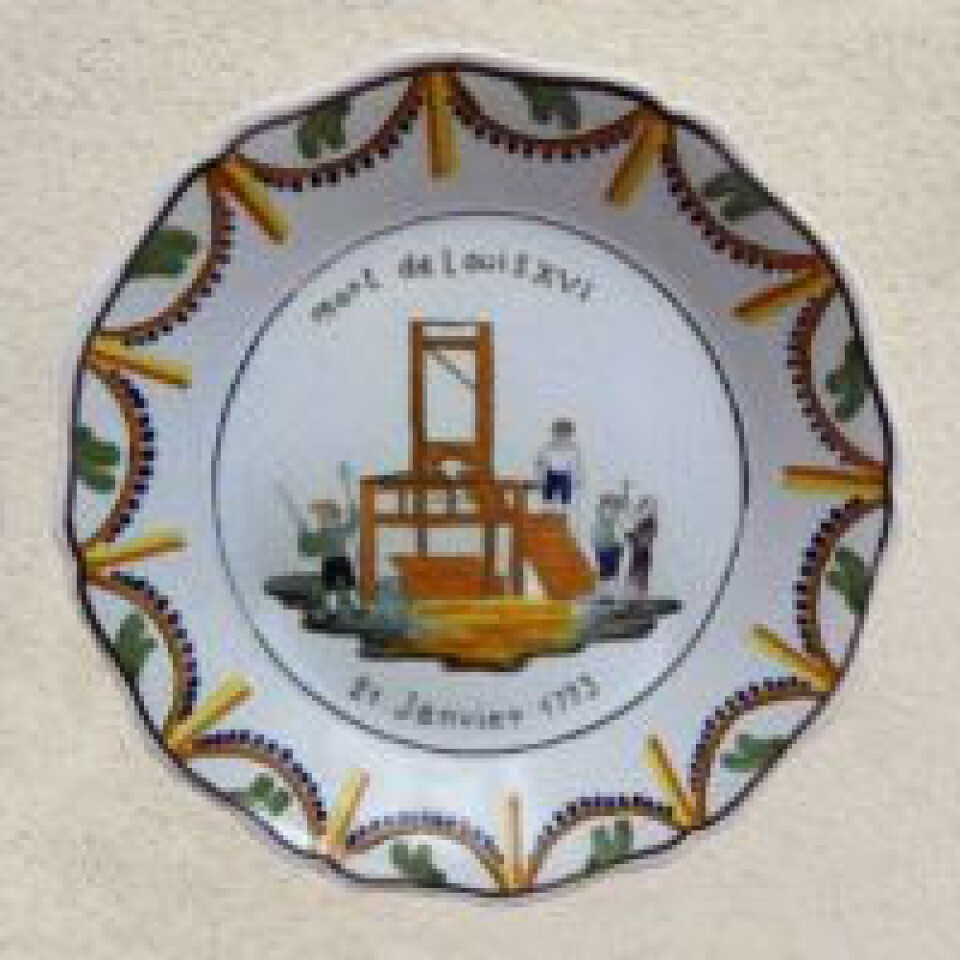

A fine example of faience patriotique.

These were plates produced during the Revolution, showing the stages of Louis XVI’s execution – like our coronation mugs but with a macabre twist.

They were for prominent display, to make clear to visitors in those times of casual denunciation that the owners had lost none of their republican fervour. A snip (sorry, Louis) at €20.

Photo: Michael Delahaye

-

A humble hammer, but in itself a work of craftsmanship.

Like many old French tools, it is beautifully wrought, ludicrously over-engineered and a joy to handle. €10.

Photo: Michael Delahaye

-

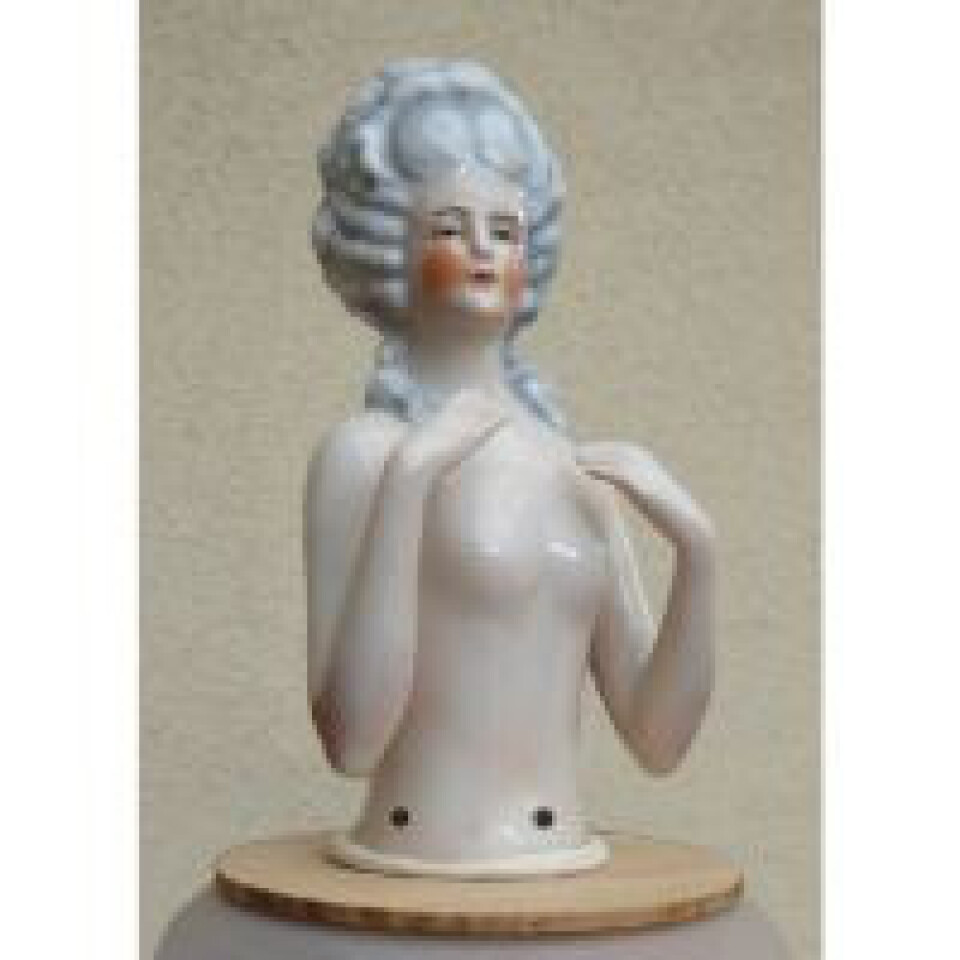

A so-called ‘half-lady figurine’ in classic modesty pose (or Madame de Pompadour after a botched conjuring trick).

As the holes around the midriff indicate, it was originally attached to a voluminous skirt that acted as a hatpin-cushion and would have sat on a society lady’s dressing table. €20.

Photo: Michael Delahaye

-

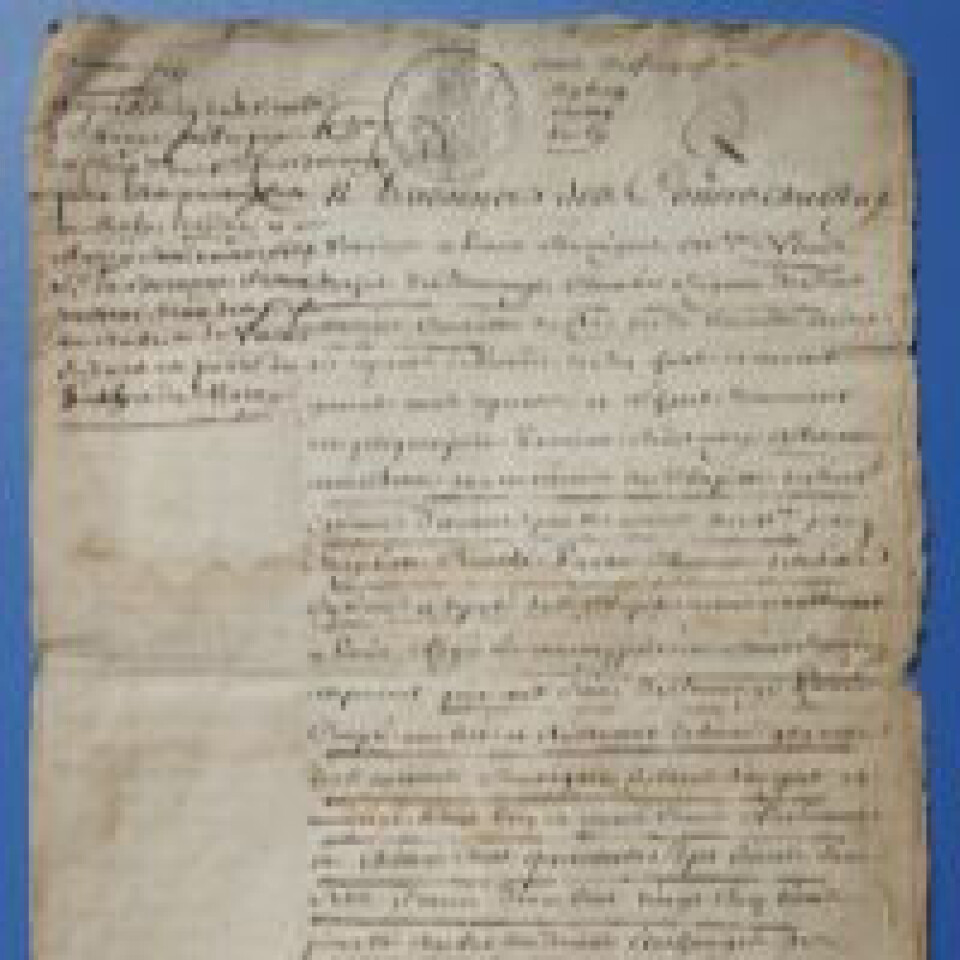

A notarised property conveyance. Part of a portfolio of old documents I picked up for €12.

When I looked more closely, I realised I was ‘holding history’: it was dated August 27, 1715 – six days before the death of the ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV.

Photo: Michael Delahaye

A relatively modern ceramic bust of Napoleon, with hawk nose and forward-combed quiff. It was bought not because I am an admirer of l’Empereur, but for its uncanny resemblance to the current occupant of the Elysée Palace. €20.

Photo: Michael Delahaye

Incidentally, do not overlook what are often dismissed as ephemera – those piles of magazines, usually stacked on the ground.

The adverts – for cars, corsets and cures for digestive complaints – offer a fascinating glimpse into the pretensions and preoccupations of the upper classes.

Most striking, though, is the quality of the artwork.

One of the most popular large-format weeklies was L’Illustration, published for over a century from 1843 to 1944.

Long after the invention of photography, it still employed graphic artists who – just one example – were capable of recreating, in detail and presumably from memory, a World War One battlefield.

As will be clear from my list, I set myself a limit of €20 per item.

“Go with an open mind but a tight wallet” is my mantra.

How to get the most out of a ‘brocante’

For more general guidelines, I consulted the most serious frequenter of brocantes I know – a retired friend who lives in a house which itself could pass for a three-storey brocante, such are the number of items covering every surface.

Pete, as I will call him (he is a shy shopper), spends every weekend during the season on ‘brocante crawls’. He is an occasional collector and has done a bit of online trading.

He readily admits he is really just a sucker for finely crafted items at absurdly low prices.

If anybody knows how to get the best out of a brocante, it is Pete. So…

Question 1: How do you haggle?

Pete’s advice is to speak French even if your command is limited: “At least know your numbers and memorise the important phrases.”

Perhaps the most useful: Quel est votre meilleur prix, Monsieur/Madame? And, Pete adds, always be polite: aggressive haggling seldom gets results.

It is also worth remembering that the traders know what they paid for every item and therefore how much of the profit margin they can afford to shave.

As an aide-memoire, some will stick on coded labels of the paid price.

Traders in the UK do the same. One of the standard codes is HONESTLADY, each letter representing a number from 1 to 10. Sadly, I have never discovered the French equivalent!

Question 2: What is the best time of day to go ‘brocanting’?

Professional antique dealers typically arrive before dawn as the vans are being unloaded to grab the choice items at trade prices.

Pete is more relaxed and turns up around 9:30.

By then, he points out, the brocanteurs will have set up their stalls and have everything out on display but the potential competition, the tourists, will still be in their chambres d’hôtes having breakfast.

Question 3: Is there a pattern to the day?

Definitely. From midday onwards, prices can become seriously intéressants and the traders more amenable to negotiation.

Some will make up job lots and highlight their reductions with handwritten notices.

So, in theory, the later you leave it, the better the potential deal.

According to Pete, this applies particularly to furniture and bulky items which the traders would rather sell at a discount than heft back into the van.

The downside, of course, is that you may end up with no deal at all because, by the time you make your move, the object of your desire has gone.

In the end, it is a fine calculation: a matter of determining le bon moment – or, as even the French occasionally say, le juste timing.

For the record, my own ‘one that got away’ was an ornate, metre-high zinc insert for a Mansard roof which would have made a wonderfully dramatic mirror frame.

Inexplicably, my wife did not share my disappointment.

Related articles

Brocante vendors in France limited to just two events a year

How to insure and prove value of expensive items at your French home

What do I need to do to organise a vide-maison sale at my French home?