-

The origins and meaning of tirer les marrons du feu

As Christmas approaches, we look at a phrase to describe someone who takes advantage of a situation

-

Saint-Aubin-des-Châteaux: rural French village with historical and natural charm

Step back in time to explore Neolithic, Roman, and Templar traces... but you will not find any châteaux

-

Owners of French mill seek help tracing history

'We are looking for old photographs from before it closed,' say couple who restored the building

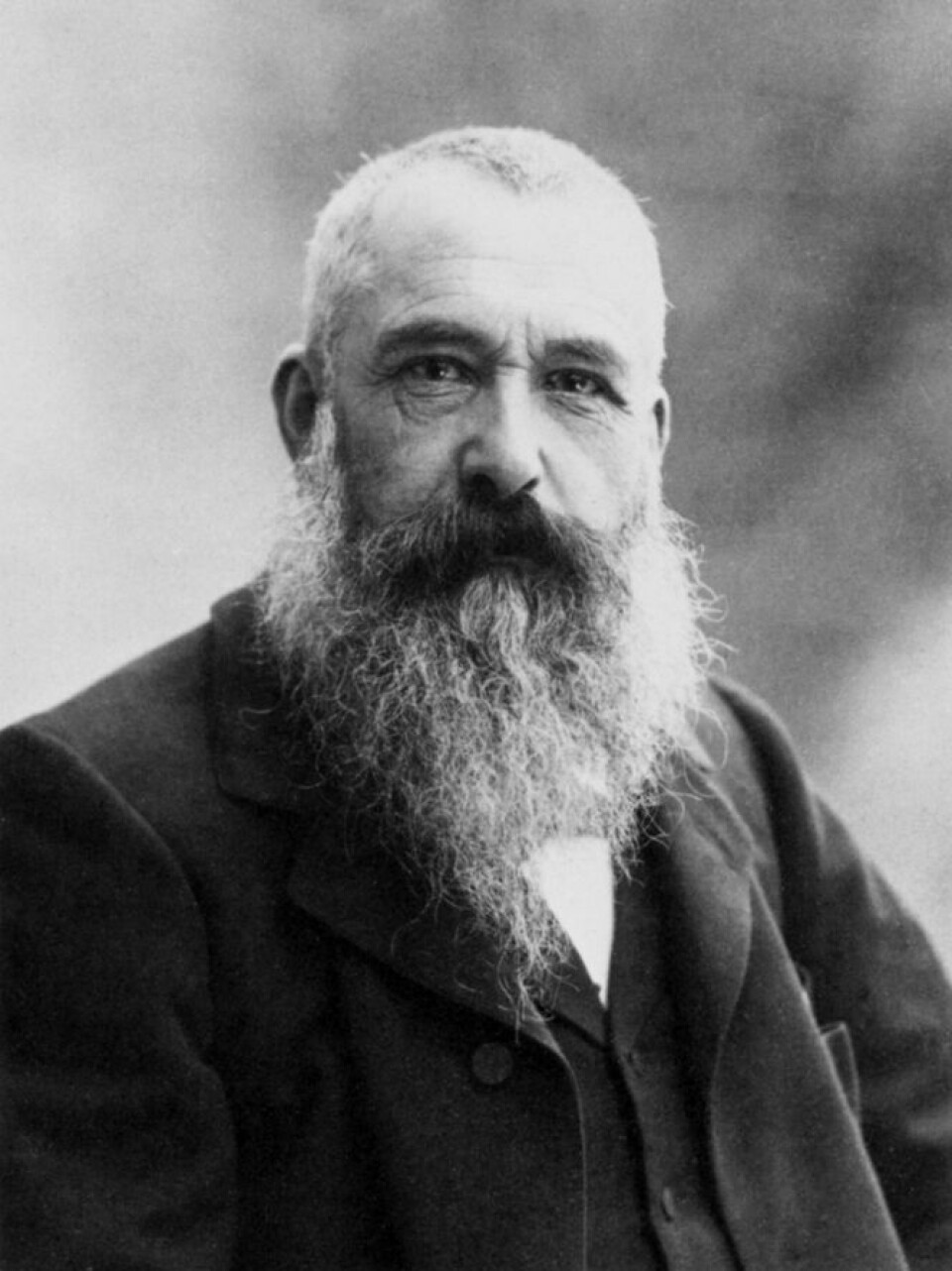

Claude Monet: French impressionist who went to war for his art

In 1861, Monet was drafted into the army and sent to Algeria. His rich father refused to buy him out unless he agreed to give up painting, but he refused

Claude Monet (1840-1926) is such a popular artist today that it is hard to imagine him struggling for recognition as a young painter, and even harder to imagine an art world without French Impressionism – even the term derives from his painting, Impression: Soleil Levant.

Born in Paris, his family moved to Le Havre when Oscar-Claude was five years old, and from childhood he always wanted to be a painter.

His mother, a singer, supported him – but his father would have preferred him to go into the family’s grocery business.

Luckily for the world, Monet got his way and started training when he was 11 years old and already locally known for selling charcoal caricatures.

He would paint for the rest of his life despite only gaining recognition and a steady income from his art when he was already in his 50s.

Monet’s mother died when he was 16 and he was sent to live with an aunt but continued painting, mostly landscapes.

Read more:Monet museum is named best in France based on visitor reviews

In 1861, he was drafted into the army and sent to Algeria. His prosperous father refused to buy him out unless he agreed to give up painting, but Monet refused point blank. A year later, he contracted typhoid, and eventually his aunt arranged for him to be discharged and go to Paris to study art.

Monet, however, quickly became disillusioned with the teaching he received. He did not want to paint in the conventional style of the era.

He wanted to develop something new – a way of capturing the way light changes colours and shapes. Along with Renoir, Bazille, and Sisley he began experimenting with broken colours applied with rapid brush strokes to render a fleeting impression rather than a detailed record.

He shuttled frequently between Paris and Normandy during this period, staying regularly in Honfleur.

At the time the most influential art exhibition was the Salon de Paris, organised by the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

A painter whose work was refused was left out in the cold.

Monet had some paintings accepted, including Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress), using Camille Doncieux as his model. His work was well-reviewed, and he began to be noticed although he still was not making much of a living.

Read more:Exploring the homes of France’s great artists

Forced by lack of money to return to Normandy, he painted beaches and seascapes. He also painted Camille many, many times, and in 1867 she gave birth to their son Jean.

They survived by borrowing from friends because Monet’s family would not help. The artist was in despair but never stopped painting, and in 1868 he was commissioned to produce a series of paintings for a rich businessman.

Constantly moving from one lodging to another, in 1870 the pair finally married in Paris.

The Franco-Prussian War broke out that year, and Monet moved to London. His father died in 1871 but he did not go to the funeral, fearing he might be conscripted into the army. He moved to Amsterdam instead, where he painted 25 canvases in four months. At the end of the year, using money he had inherited, Monet and his family returned to France and moved into a house in Argenteuil.

He bought a boat on the Seine and used it as an art studio. Frustrated by the lack of recognition from the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Degas, Cézanne and Sisley held their own exhibition in 1874.

A total 165 works were shown; around 3,500 people paid 60 francs each to see the exhibition – but Monet’s painting, Impression: Sunrise (priced at 1,000 francs) did not sell.

A reviewer commented acerbically that the paintings were indeed ‘Impressionist’, and a new school of art was baptised.

Family health matters took over for a while. Camille was diagnosed with TB in 1876, and her condition worsened with the birth of her second son, Michel, in 1878, when she was also diagnosed with cancer. She died the following year, tragically young.

Monet sat at her bedside – realising with horror as he painted that despite his distress, he was automatically noting the individual colours on her dead face (Camille Monet on her deathbed is now in the Musée d’Orsay).

Monet’s work focuses on the study of how light changes colours, and how colours in proximity interact with each other. He was fascinated by reflections and how to paint them.

One series of paintings made at St-Lazare station investigate how smoke and steam affect colour, and how sometimes they are opaque and sometimes translucent. He was also interested in how mist and rain affected colours.

The reason for painting the same scenes over and over was to chart the way the changing light altered colours throughout the day and across the seasons.

He painted four series in London: Houses of Parliament, Charing Cross Bridge, Waterloo Bridge, and Views of Westminster Bridge. He also travelled to the Mediterranean, painting landmarks, landscapes and seascapes as well as a series in Venice.

It was his own personal artistic journey, an exploration of what could be done with oil paints. He used a limited number of colours: silver, white, cobalt violet light, emerald green, ultramarine extra-fine, vermilion (rarely), cadmium yellow light, cadmium yellow dark, and lemon yellow. He excluded black, sometimes replacing it with dark purple, or a dark chocolate mixed from all his paints.

Monet was devastated by his wife’s death, and a family friend, Alice Hoschedé, took Monet’s two boys to live with her in Paris. Her bankrupt husband had returned to Belgium leaving her with six children, so perhaps two more did not seem significant.

The following year, she and all the children rejoined Monet in Vétheuil – and in 1883 he discovered the house in Giverny (Normandy) where he would live for the rest of his life.

Having rented his dream house, life finally began to run more smoothly. There were orchards, a garden and a barn where Monet could paint. There was a school for the children, and the surrounding countryside offered a variety of beautiful scenery to paint.

Monet’s paintings began to sell and by 1890 he had earned enough to buy the house outright. In 1892, when Alice’s estranged husband died, she and Monet finally got married and there was enough money to build a new art studio, extend the gardens and add a greenhouse.

Monet became passionate about the gardens, creating scenes he wanted to paint. He would write daily instructions to a team of seven gardeners about the design, planting layouts and purchasing of new plants.

In 1893, he bought an adjacent water meadow and launched into landscaping that area too, including the creation of the lily ponds which he would spend the last two decades of his life painting.

Alice died in 1911, and his oldest son Jean died in 1914, leaving Alice’s daughter (also Jean’s widow) to look after Monet as he developed cataracts. He had spent his life straining to paint exactly what he saw and he continued even as his sight deteriorated, his colour palette becoming dominated by reds and yellows.

His work from this period shows the details fading and blue vanishing.

Monet made a series of weeping willow paintings during the First World War in reference to the fallen soldiers but painting was becoming increasingly difficult.

He lost the sight in his right eye completely and, by 1922, had stopped painting altogether. A year later, he was persuaded to have surgery, which restored the sight in his right eye.

He refused to have surgery on his left eye and used special glasses with green lenses in order to start painting again. He even went over some of his pre-surgery works, making them more vivid, and often intensifying the shades of blue.

He continued painting until shortly before he died of lung cancer in 1926, at the age of 86.

He was buried in Giverny churchyard. He died intestate, meaning his surviving son Michel inherited his entire estate.

He never lived at Giverny, did not have children, and on his death in 1966, bequeathed the house and the gardens to the French Academy of Fine Arts.

Over the years it has been restored, and now attracts visitors from all over the world. It is normally open to the public, but in the current circumstances check giverny.org before planning to visit. Tickets must be bought online.

Related stories:

Simon Beck: The artist reveals the secrets of his snowshoe drawings

Meet the artist behind France’s new Napoleon commemorative sculpture

From poverty to glory: Life of legendary French singer Edith Piaf