-

Why your accent should not hold you back when speaking French

Columnist Nick Inman notes that some French people are harsh judges of foreign speakers

-

Visitors to Normandy American Cemetery must soon book in advance

With more than one million visitors last year, the cemetery is one of the region’s most-visited D-Day sites

-

Learning French: what does sacquer mean and when should it be used?

You may be able to guess one of the meanings behind this informal term that sounds just like an English equivalent

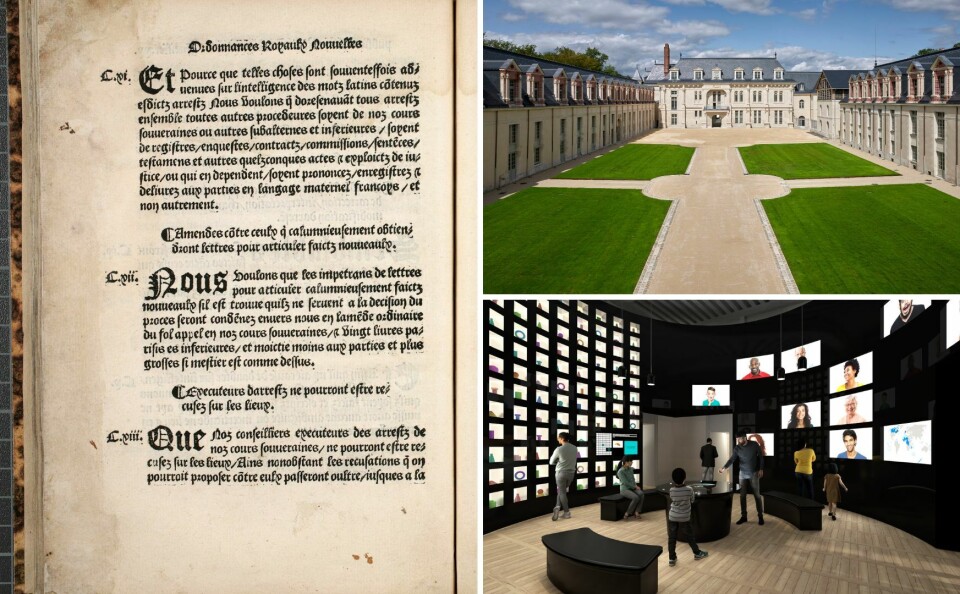

President opens 'first-ever’ centre dedicated to French language

The chateau where François I ruled that French, not Latin, should be used has been renovated to celebrate the fun and vitality of the language

President Macron is today inaugurating what is claimed to be the "first project in the world dedicated to the French language".

Culture Minister Rima Abdul-Malak, who is accompanying him, made the statement, adding that the new Cité internationale de la langue française "brings together the strength of the French language and a recognition of its diversity". It is "destined to become the beating heart of la francophonie" [the French-speaking world], she said.

The centre's displays aim to be fun, and showcase such diverse elements as rap music and slang as well as different French words and expressions from the different French-speaking parts of the world.

However, the location – a newly-renovated Renaissance chateau – has a special meaning of its own in the history of French.

Among the exhibits is the actual Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts, signed at the chateau by king François I, establishing French as the official language in 1539.

However, its director Paul Rondin told The Connexion it is not a museum or somewhere to conserve the language, but rather “a place where we bring French to life and show off its vitality”.

President Macron involved in creating concept

Situated north-east of Paris, the former royal palace has had many uses over the years – royal court, barracks, workhouse, retirement home – and has never been opened to the public until now.

It has been saved from a state of abandonment in a transformation with a total budget of €211million.

The idea behind it, which originated with President Macron, was not to renovate it out of purely historical interest. In any case, recreating the original Renaissance style would have been difficult as the interiors had been gutted, with its grand spaces divided into utilitarian rooms and dormitories.

It is still possible to see grand staircases and the royal chapel, but its new role is to house displays and activities about the history and diversity of the French language.

The inauguration had to be pushed back from October 19 so Mr Macron and his wife, Brigitte, could attend the funeral of the teacher recently murdered in Arras.

Read more: Teacher killed, two injured in terrorist knife attack at French school

The unique cultural space will open to the public from Wednesday (November 1), and will offer special tours, readings, talks, comedy and music shows, and more.

Common language was attempt to bring equality

Mr Rondin said Mr Macron came up with the language theme because of the historic link with the Ordonnance, which Mr Rondin said represented an early attempt to foster equality and bring the people of France together.

It was “quite revolutionary” and meant everyone, not just priests or lawyers, could understand laws and official documents.

It was also a unifying force in times when many people spoke other regional languages in daily life.

“It was the launch of something. It created structure around what language is going to allow us all to share, exchange, discuss about our rights and obligations,” he said.

Read more: France’s tug-of-war between its regional languages and official French

Celebrates slang, poetry, and borrowings from other languages

Even so, Mr Rondin said the centre celebrates the different French languages, in the plural, and does not seek to impose the dominance of standard French, as was in place at some periods.

For example, the Abbé Grégoire, priest, politician and revolutionary, who had wanted to stamp out regional languages, or the Jules Ferry laws of the 1880s, which said French was the only language that could be used in schools.

The Cité has sections devoted to these other regional languages but also celebrates influences including rap, slang, chanson and poetry, and borrowings from other languages: it also looks at French from around the world, such as Africa, Quebec and Asia.

Read more: 10 words used in Quebec that mean something very different in France

More open and playful than the Académie française

When it comes to French language institutions, we often think of the Académie française, which has a reputation for being conservative in accepting change.

Mr Rodin said the Académie has an important role and it can sometimes be good to take one’s time, but the Cité will act as a counterpart where they will foster an especially open and playful approach to French.

“Language can be exciting, and that’s what we have to bring out,” he said.

“As you follow your route through our 1,200m2 of space, you will find interactive displays where you play with the language.

“It is at the same time serious, it’s been conceived by a committee of top-level experts, but almost a kind of fairground ride, presented in a joyful, playful and impressive way.

“We are talking about living language and we are open to everything because we have absolute confidence in the vitality of French today.”

Read more: Franco-Lebanese writer is new guardian of the French language

Role of gender in French language

He said there are around 300 million speakers of French, plus many people who are francophile and love French cultures, of which the language is one part, even when they do not master it.

French is a part of that cultural “colour”, not just something “utilitarian”.

One issue among the many explored in the displays is how the masculine gender came to have a more dominant role grammatically (it was not always the case) and how contemporary ways of speaking are seeking ways to include women more.

“Sometimes, perhaps, it’s better to take a little longer to say things well,” Mr Rondin said.

Expressions from Quebec, Haiti and the Congo

Other interesting elements include looking at the way words have migrated – how their sounds and letters have evolved and how they have travelled around the world.

“There’s a kind of immense world map where we can see the way words have circulated.”

There is also a game using expressions, which encourages people to think about different ways to say the same thing.

“It is fun, and shows how language can be a kind of huge playground,” Mr Rondin said.

Other activities look at the definitions and stories behind expressions, as well as how the same thing is said in, for example, Quebec, Haiti or the Congo.

Learn more at cite-langue-francaise.fr

Related articles

10 Breton phrases to take with you to Brittany

‘How to think like a French person and speak better French’

‘Jourbon!’: What is France’s backwards slang Verlan?