-

The origins and meaning of tirer les marrons du feu

As Christmas approaches, we look at a phrase to describe someone who takes advantage of a situation

-

Paris metro station Villejuif-Gustave Roussy named world’s most beautiful

International architecture award supported by Unesco given to stop on metro line 14

-

Commuter boat service planned for Paris

‘River metro’ could soon become a reality on the Seine

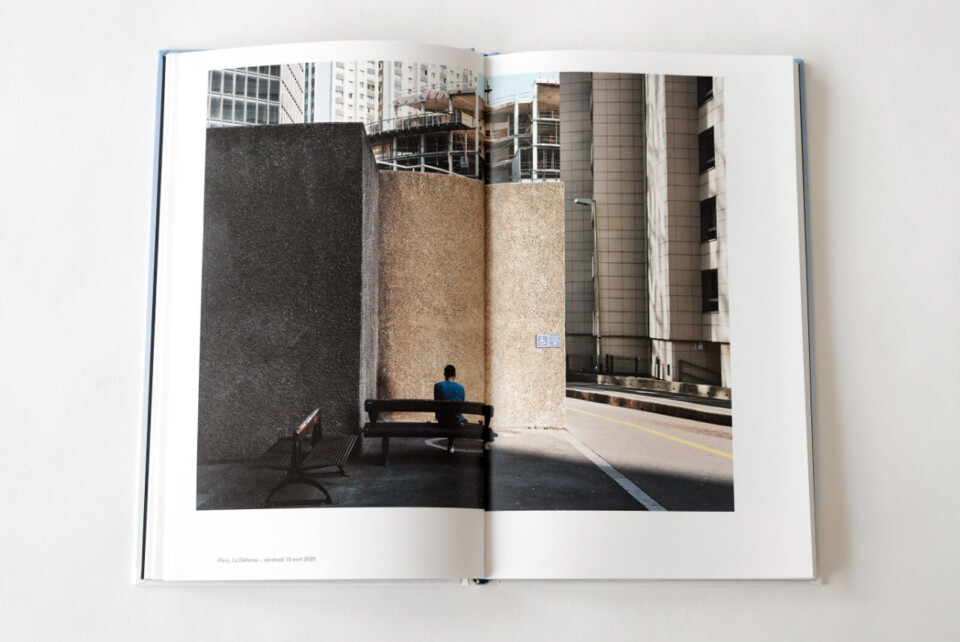

Parisian photographer shows a much darker side of the City of Light

Photographer Myr Muratet is putting the grittier side of life in Paris in the frame

Behind a typical Haussmann building in the 10th arrondissement of Paris hides a former assembly plant which has been transformed into workshop/studio space.

On the Sunday afternoon I visit, the complex is quiet and the doors of most of the 26 studios are open.

In the courtyard, beyond a fence, a woman is watering flowers. Wroughtiron walkways connect the two buildings which make up the site.

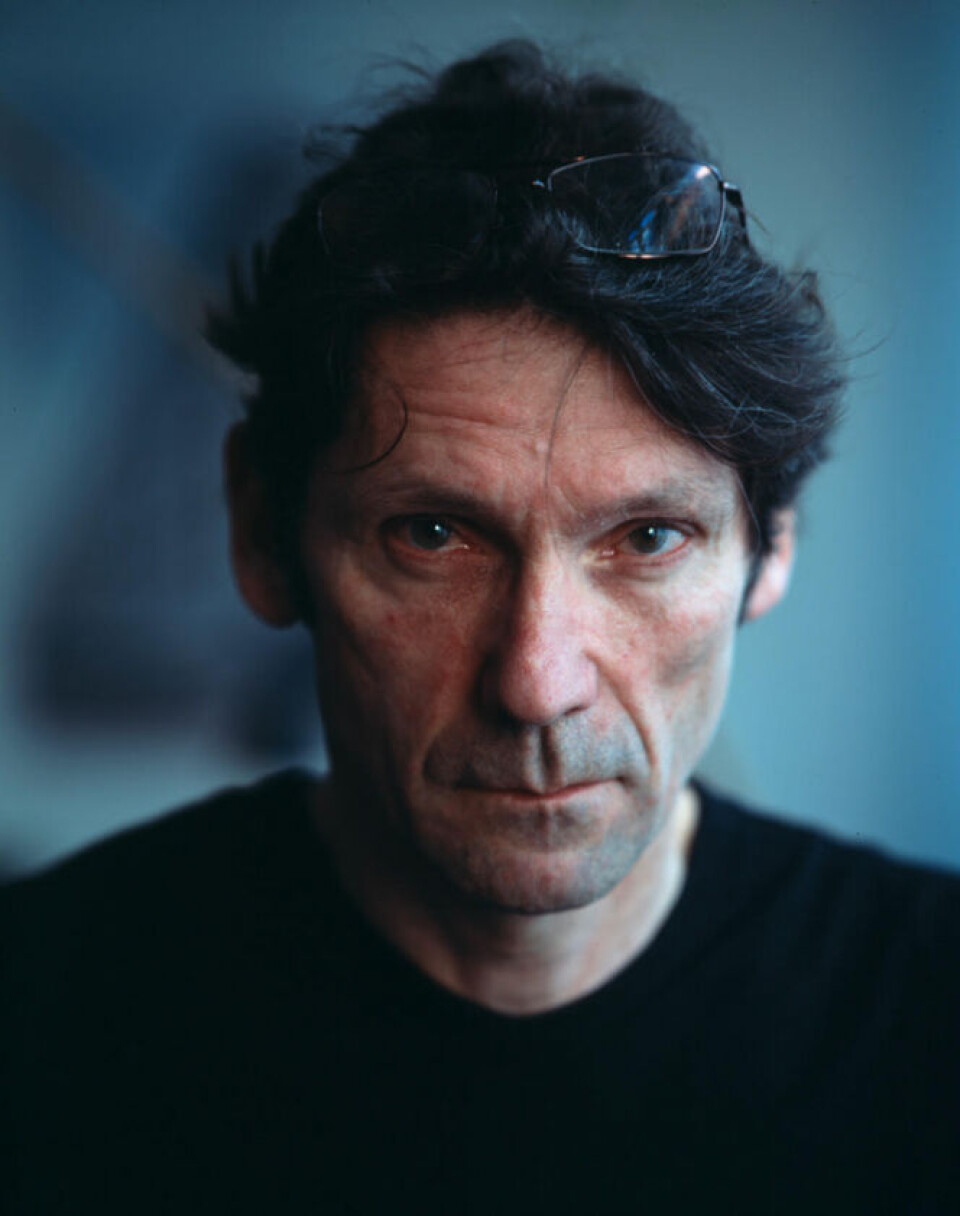

In one of these studios works photographer Myr Muratet. Greeting me with a smile, eyes twinkling behind glasses, Myr is very approachable.

“Would you like some coffee?” he asks, gesturing to an Italian coffee pot.

Against one of the walls stands a large, framed photograph. Close-up and giving a frog’s-eye view, it shows two middle-aged men, Laurent and Patrick, in the middle of what looks to be an argument or heated discussion.

The photograph forms part of Myr’s Paris Nord project, the result of two decades pointing his lens on the capital’s most marginalised demographic.

After studying photography in Hamburg, Myr returned to his native city and began to capture the lives of homeless people at Gare du Nord.

For more than a decade, he shot pictures of his subjects in and around the railway station. He followed his subjects to the point where they forgot about his presence.

The framed photograph dates from 2004. Since then, Laurent has disappeared, while Patrick is now dead.

“Most of my subjects have died,” Myr says. “The mix of alcohol and buprenorphine [a prescription drug used to treat opioid dependence, including heroin] is ravaging.”

When Gare du Nord was turned into France’s main high-speed railway station, it became not only Europe’s busiest station, serving 700,000 users per day, but also many tourists’ first impression of Paris.

As such, security has tightened since Myr first started shooting here.

Anyone who hangs around the terminal is rapidly moved on.

Recently, TV channel Arte filmed a documentary on Myr. They hoped to show him in action here, but security guards would not let it happen.

Efforts to dissuade people from lingering in the station have included the installation of so-called dispositifs to act as deterrents.

Chairs provide a half-standing position rather than comfortable reclining, for example, while sharp steel pins cover the windowsills.

Myr explains that design agencies often participate in competitions for ever more creative ways to clamp down on loiterers.

“Can you imagine designing such things?” he asks.

When I quiz him about whether other railway stations will follow suit, including the nearby Gare de Lyon, he says he does not know. His work, he says, is limited to very specific people and places. He is not a sociologist: “I do not want to tell a story.”

In Paris, dispositifs are becoming omnipresent, installed by private entities as well as public bodies.

At Porte de la Chapelle, for instance, the authorities razed a travellers’ camp below the ring road and planted large rocks to prevent them returning.

Then refugees occupied the spot: they slept between the rocks or on wooden shelves they placed on top.

Finally, the authorities encircled the entire spot with a fence reaching as high as the motorway.

Although Myr’s photographs often depict extreme situations, he says there is never an intent to shock.

'I am not interested in showing poor people. I am interested in showing how people organise their life in a particular place'

He gives the example of Calais, where barbed wire, gates and ditches – all of them dispositifs – not only hinder the migrants but also complicate life for residents.

The Paris Nord of Myr’s project refers not only to Gare du Nord, but north Paris generally. Some 244 photographs were taken in the city and the Seine- Saint-Denis department, as well as some in Calais.

Myr insists on using an analogue camera. Although it is large and heavy, requiring a tripod, he does not compromise on quality.

His photographs demonstrate rigid composition and perspective.

After working on numerous advertising assignments in the 1980s, when black-and-white was fashionable, Myr prefers working in colour.

He says analogue cameras are particularly good at rendering green shades and skin tones.

His studio contains a small library of photography books. Myr admires in particular the work of Eugène Atget, who photographed Paris around the turn of the 20th century.

The huge book he shows me has photos of street vendors, rag pickers and knife grinders. With his expensive, bulky camera – “even larger than mine” – Atget ventured into La Zone, Paris’s notorious shantytown.

As Haussmann kept embellishing the City of Light, Atget immortalised a Paris which was fast disappearing and whose inhabitants were being displaced as a result.

Similarly, most places Myr has photographed no longer exist today: the squats have been torn down and the travellers’ camps have been razed.

Arte used a quote of Myr’s as the title of its documentary: “In the end, there will no longer be any poor people in Paris.” Myr himself lives in an area which has fallen victim to gentrification, Marx Dormoy.

Myr accepts hardly any media assignments

Recently, a newspaper wanted to run an article on how the Roma community had fared during the pandemic. Myr, who more than a decade ago met a Roma family and became godfather to one of their children, refused.

“I told them it took me 10 years to understand the Roma. The newspaper said they didn’t have 10 years.”

A recent lockdown book aside, all of Myr’s projects are longterm ones.

Wasteland, for instance, was launched in 2009 in collaboration with Myr’s elder daughter, who holds a PhD in ecology, and graphic designer Marie Pellaton. In 2017, the project culminated in a book called Flore des friches urbaines, an inventory of the flora of Seine-Saint-Denis’s numerous wastelands.

One of a kind, the book’s first edition sold out fast. The Muratets are currently splitting costs with the publishing house to bring out an updated edition, which will contain 50 new plant species.

Is this botany book an outlier in his oeuvre, I wonder?

“Not at all,” Myr answers sharply. “The language used to describe these plants resembles the language which is applied to immigrants too. Words like ‘invasive’, ‘integrated’, and ‘exotic’.”

When an immigrant manages to integrate in his host country, he is called échappé, Myr continues, just like a foreign flower which has integrated in its new territory.

And as with all Myr’s work, the focus is squarely on Paris: the same city but another, very different, world.

Related stories

The French photography project that captures oddball constructions