-

Mass cheese recall launched in France over E.coli fears

Several major supermarkets are affected, ‘Morbier’ cheese in particular is recalled

-

Plastic in bottled water: these brands identified in France as least affected

A new consumer study claims four popular brands offer the safest water to drink

-

Discover the charm of Menton lemons and how to grow citrons in France

Sue Adams explores the rich history of France's only IGP-recognised lemon, celebrated annually at a vibrant festival

Why Roquefort is the true king of French cheeses

Casanova even said it was ideal for restoring love. We look at where the emblematic cheese comes from and how it is made

Roquefort is one of the emblematic cheeses of France and was the first to receive the prestigious Appellation d’Origine Protégée, AOP label in 1925.

The name Roquefort can only be used for a cheese produced under a strict set of regulations; it has to be made with sheep’s milk from the Lacaune breed and it must be matured for a minimum of 14 days in the famous caves of Combalou at Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, south east of Rodez, Aveyron.

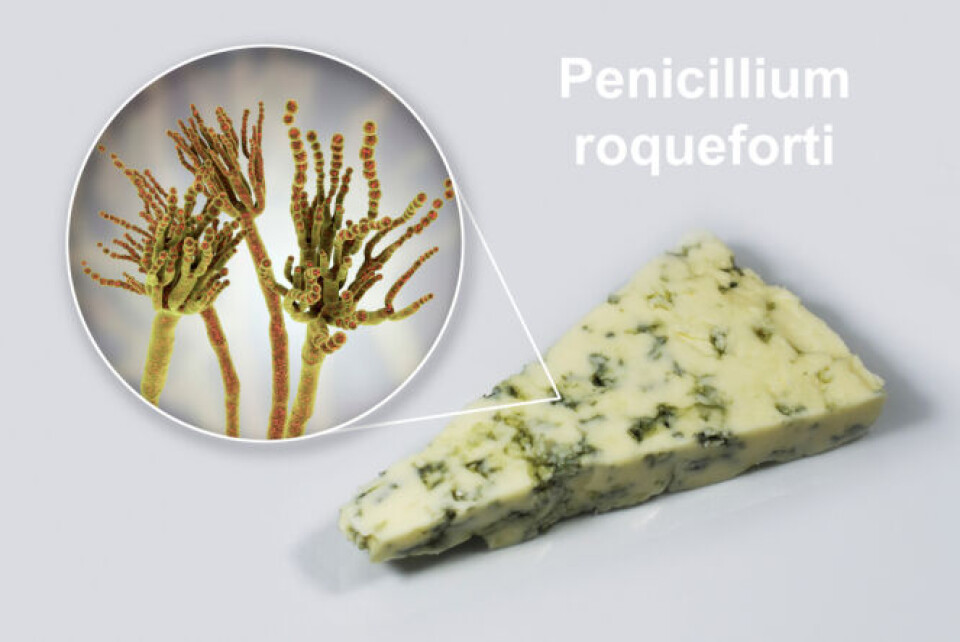

Legend has it that the cheese, famous for its blue specks caused by Penicillium roqueforti, was created by chance when a shepherd forgot his bag in a cave. When he returned some days later, his bread was mouldy and his cheese had blue veins.

Now the Penicillium roqueforti, which is harvested from spores which develop on wheat and rye bread, is the special ingredient added deliberately to the cheese.

It has been eaten and enjoyed for centuries. The first authenticated mention dates from 1070 when it was given as a gift to Conques Abbey.

In 1666, an edict from Toulouse parliament said the only “genuine Roquefort could come from the Combalou cellars in the town bearing its name.”

Famous French figures throughout history have sung its praises: the 18th century gastronome, Brillat-Savarin said a dinner without Roquefort was like a beautiful woman with only one eye. Voltaire mentioned it in his letters and in Italy, Casanova said Roquefort was ideal for restoring love.

Famous blue specks in Roquefort are caused by Penicillium roqueforti. Pic: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

The quality of the sheep’s milk is vital to the cheese.

André Boiral has 600 ewes in the Gorges du Tarn Causses, Lozère, where he has been farming since 1987.

He is one of 1,500 farmers looking after Lacaune sheep, developed from selective breeding begun in the 19th century. They have to be raised within a radius of 100km around Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, which includes part of six departments; Aude, Aveyron, Gard, Hérault, Lozère and Tarn.

Mr Boiral says they are a breed which is ideally suited to the local area: “It can be very cold in winter and dry and hot in summer and the sheep can adapt to different conditions. The territory is rocky and they know how to find the best grass. They are hardy and give a good quantity of milk, about 300 litres each a year, which is relatively rich and has a good balance of fats and proteins and a particular taste which suits Roquefort cheese.”

The season begins with the lambing. After a month to six weeks, when the lambs are weaned the ewes are milked twice a day for a period lasting six to seven months.

“With slightly different calendars on each farm, and lambing starting in different months, we provide milk, between us, for the cheeses from November to June.”

During winter the sheep are in barns, but as soon as the weather permits, they are put outside to pasture.

One of the stipulations of a Roquefort cheese is that the sheep must have a grass-based diet. 75% of all their supplementary food has to come from within the Roquefort area.

Five people work with Mr Boiral in a job which requires constant attention to detail: “We are in daily contact with the sheep, for milking, lambing, shearing, moving them from pasture to pasture, and all the other daily jobs required on a farm like ours. There is a lot of work involved to produce milk reaching Roquefort cheese standards.”

Milk is collected once a day from the farm and taken to one of seven Roquefort cheese companies.

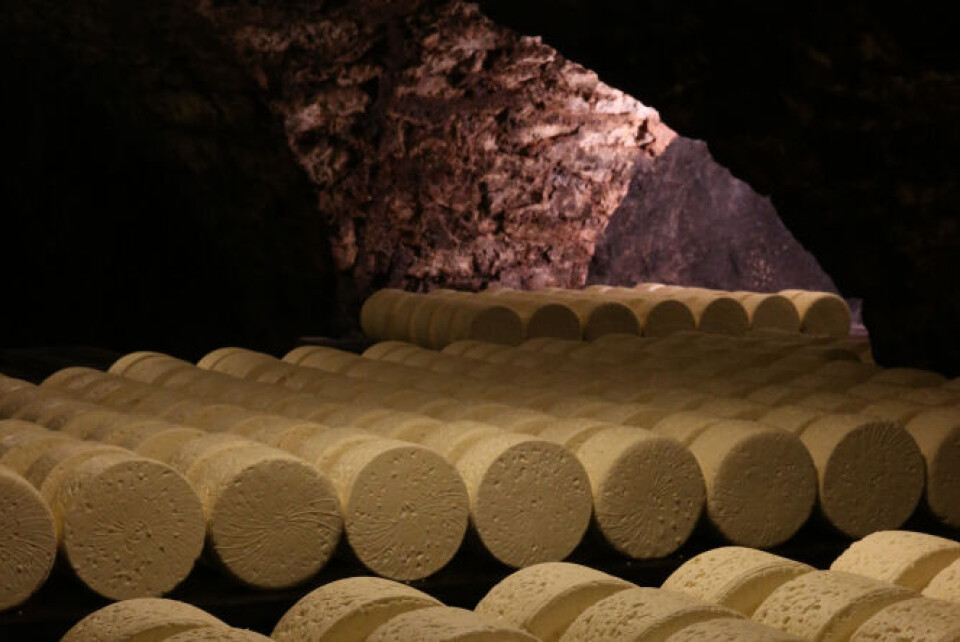

The cheeses spend at least 14 days in the Combalou caves. Pic: Les Fromageries Occitanes

The biggest is Roquefort Société, which makes over 3million 3-kilo cheeses a year, 60% of the total production of Roquefort cheese.

One of their three Cellar Masters, responsible for making the cheese, is Bernard Roques. He says the first step is to test the unpasteurised milk for unwanted bacteria and if it is clear, to add rennet and penicillin.

“It takes under an hour for the curds to form. They are cut into 1cm cubes and put into moulds, which are left to drain for three days. On the third and fifth day they are rubbed with salt and on the seventh day the cheese is pierced throughout with holes, allowing air in to feed the penicillin.”

The cheeses then spend at least 14 days in the Combalou caves, where the magic happens and the blue spots develop – giving Roquefort its unique flavour.

The geological formation of the caves is essential. They were formed over one million years ago when the Combalou plateau collapsed due to gigantic land mass movements. The resulting caves were formed with what are called fleurines, from the Occitan word “flarina” meaning to blow, which provide the natural ventilation required for the cheese to ripen.

“High humidity and a constant temperature result in the best cheeses,” says Mr Roques. “The caves are always between 10°C and 12°C, but the ripening cheeses increase the ambient temperature, which is cooled and controlled by the fleurines, which we can open and close off as appropriate. We have fourteen different caves in all and we rotate the cycle of the cheeses, so that each cave has a resting period.”

After a fortnight, the “cabin workers” (cabarnières) fold each loaf of cheese in a protective wrapping at a rate of up to 120 an hour and they are moved to refrigerated areas to be matured at a low temperature for three months, after which they can be sold.

A tasting with Jean-Louis Reyes from Les Fromageries Occitanes. Pic: Les Fromageries Occitanes

Roquefort is a seasonal cheese, depending on the milk supply, and so by the end of July there are no more cheeses in the caves. “The quality of milk changes,” says Mr Roques. “It is much more abundant and richer in the early days, with sheep producing 5 litres a day at their peak, going down to 0.5 litres at the end. Our busiest period is February, March, April and May. We have to adjust to the milk we receive as the different quality affects the end product, and we try to produce as consistent a cheese as possible.

“There are a huge number of parameters in producing a good Roquefort, which is what makes it such a fascinating and passionate job.”

Many of the cheeses from his company are sold throughout France in supermarkets. He says they are made in exactly the same way as a higher priced Roquefort sold in delicatessens, as they all have to be made in accordance with the same strict regulations.

However, he said, the best cheeses are kept aside for specialist shops, and they are different and can have a greater range of flavours. Roquefort can be made at different strengths of taste and with different strains of penicillin.

He says one difficulty the company is having to face is that consumer eating habits have changed:

“People do not always eat a cheese course with their meal any more. In restaurants you are now often offered either a desert or a cheese platter, and people often choose the sweet option. We are therefore diversifying to suggest other ways of eating dishes including Roquefort, like quiche, and creating recipes to show how best to include it in cooking and salads. Roquefort does go very well with many ingredients, particularly with fruit.”

He says his favourite is eating a small piece of Roquefort with bread and quince pâté.

The Roquefort Société Caves can be visited all year round (outside Covid-19 health restrictions) though cheeses are only matured in them from January to July.

www.roquefort-societe.com/the-caves

Related stories:

French engineers build website to calculate ideal raclette quantities

Roquefort seeks exemption from French Nutri-Score label scheme

How I changed career: Banker to cheesemonger in France