-

From English teacher to TikTok star in France: 'The way to help students learn is to believe in them'

Toulouse-based Monsieur Prof's educational videos on learning English are a social media sensation

-

‘The first baby hedgehog we rescued was love-at-first-sight’

We speak to an expert about her hedgehog health centre and how to make your garden more hedgehog-friendly

-

Ballet lessons bring health benefits to over-55s in France

Online classes with the Silver Swans are transforming lives of older adults

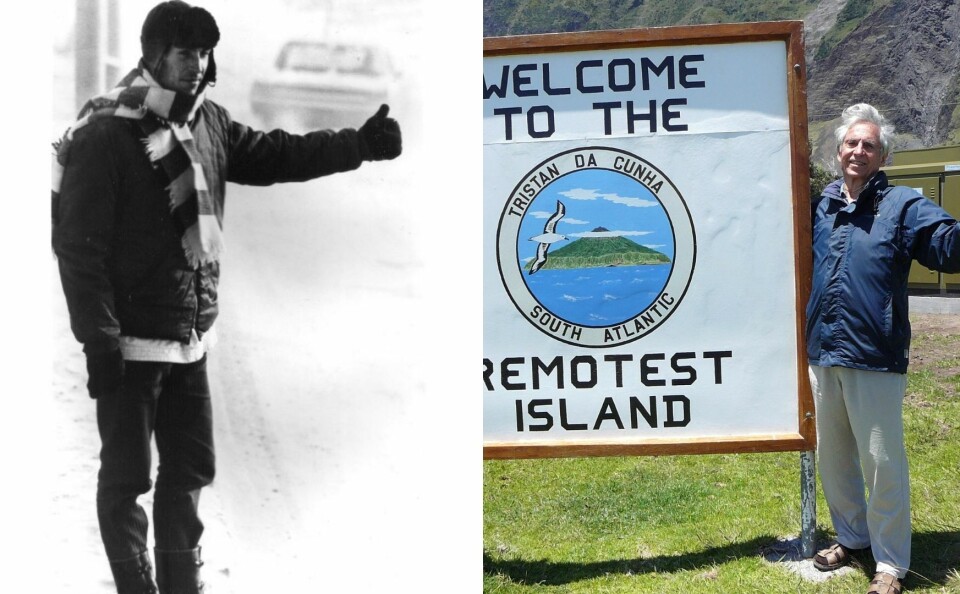

France’s 84-year-old globetrotting ‘Tintin’ shares his life lessons

We talk to a French adventurer about his amazing life on the road, the wisdom he picked up and how he thrived on a dollar a day

André Brugiroux has been jailed seven times.

He has been mistaken for a spy, a guerrilla fighter, and an air pirate.

He avoided being shot almost ten times, having dodged Venezuelan army weapons, Afghani soldiers’ bayonets, and the cold metal of a policeman’s handgun canon in Jordan.

The 84-year-old Frenchman is the living embodiment of Tintin, the cartoon character and popular reporter created by Belgian cartoonist Hergé.

A few experiences, however, are more reminiscent of 007’s dangerous encounters in the James Bond films.

Monsieur Brugiroux is France’s greatest globetrotter, having travelled around every single country and territory since 1955, when he landed in Scotland and took on an adventure he neither planned nor expected.

He is listed as the fifth greatest globetrotter in a dedicated website in which the globetrotting community records its travels.

His life and accomplishments led to a prolific career as a writer, with his books contemplating the idea that Earth is essentially one big home.

His first book, One People, One Planet, published in 1975, was translated into English in 1991.

The pin-studded map on his wall is laced with black and red ribbons, which signpost his ventures and represent 45 years of travels.

He spoke to The Connexion about more than just beautiful landscapes and fond memories.

“I did not take a sabbatical year. I took a sabbatical life,” said Monsieur Brugiroux.

Our 90-minute conversation spans his lifetime and encompasses many subjects, including his hope that humanity can reach peace, and his personal quest, in which he found himself encountering an obscure and little-known religion, the bahá’í faith.

“I travelled around the world to meet people and to reach the heart of humankind,” said Mr Brugiroux.

Was travelling around the world part of the plan when you first landed in Scotland as a young man?

Never did I think I would do all of that. I was 17 years old. We had no phone, no TV and people were caught up in the post-war reconstruction effort rather than thinking about travelling.

I had no money and absolutely zero knowledge. But I always had an insatiable curiosity.

My godmother had offered me a travel book filled with stories, drawings and anecdotes from around the world. And I wanted to see it for myself.

I remember I told my mother that I wanted to learn English after hearing two Americans speaking in the Metro in Paris when I was seven or eight years old.

I realised that I would learn English much faster by working in the hotel and catering industry, because foreigners came to the hotels and restaurants of Paris.

I was offered my first study abroad programme in Scotland when I was 17 as a student of a catering school in Paris.

I told the director at my interview that I was ready to swim the Channel to earn a place on the programme.

I left with 10 francs (around £1.30 today) in my pocket and headed off for Scotland by train from Paris.

I never thought I would come back to France after 18 years of travelling during the first phase.

I did not tell my parents: ‘See you in 18 years’. It was not like that.

How did your adventures start, and how did they gain momentum?

Things went a bit against my will initially. I learnt English in Scotland, but after 15 months I was told I could no longer stay.

I went to Spain, where I found a job overnight as a receptionist in Córdoba.

I realised then that luck comes to those who look for it.

I had to leave Spain to complete my mandatory military service.

Because I expressed an interest in learning German, the military sent me to Germany.

After two months there, I understood that people serving there were sent to Algeria to help with the war effort.

I wanted to avoid the war at any cost. Therefore I asked to be sent to Congo, the country furthest from France which still had vacant positions. I stayed in Congo for two years.

I returned and stayed in Germany for two years. Then I went to Cortina, in northern Italy, where I was lucky enough to get a job as a doorman in a hotel.

I held this position for two years and learned Italian in the process.

After Italy I wanted to go to Russia, but unfortunately, I wasn’t able to get my hands on a work visa.

The United States initially refused me. I ended up in Canada in 1965, where I worked as a translator for three years.

How did you come up with the ‘One dollar per day’ concept?

In Canada I understood that I could save enough money to pay for my trip around the world.

I went to the Universal Exhibition in Toronto to study the countries I planned to visit along the road. I lived for six years with the money I earned from three years in Canada.

I started my trip in Northern, Central and South America.

While camping for a month with an American and Mexican I figured I had spent 30 dollars in a month, or roughly a dollar a day.

From there, I just told myself : If you keep on this track, the world is yours to see. I mean, one dollar! Come on!

How did you manage to keep your costs so low for so long?

Well, food, housing and travel were all free.

I was forced to sleep in a hotel one night in the USSR while they were sorting out my visa. It cost me 11 dollars.

They wanted me to pay for six nights at a hotel after our train got delayed because of their fault. I told them I would sleep in Red Square. I would have done it. I was ready as hell to do it.

I managed to find a Russian who was willing to house me, and then took a train to Romania.

The Russians are the only ones to have made me pay for accommodation. This is an indelible crime. I will never forgive them for it.

The main problem for a globetrotter is not finding accommodation so much as travelling, since two thirds of the Earth is covered by water.

I hitchhiked by boat, plane (the hardest to do), and by train.

I lived with hippies in San Francisco and the bhikkhu (ordained monastics) in Bangkok to learn about Buddhism.

I went to schools in India and learned yoga. I worked in a Kibbutz in Israel. I lived among the so-called head cutters in Borneo.

I interrupted my first trip in 1973 after drinking poisoned water in Pakistan.

I weighed 52 kilogrammes and was running out of cash. I had visited 135 countries but I was exhausted.

What did you learn along the way?

I always asked myself why this life felt heaven sent. This is not trite. I don’t know anyone else who has done this. I asked myself why am I the only one?

I think everybody has a path. The art of life is to find your path. But finding your path is only the beginning. You then have to walk it, which is not as easy as it seems.

After 12 years spent travelling, I understood that the question I most wanted answering came from wartime.

I think I wanted to experience whether human beings were capable of finding peace with each other.

My question was ‘is peace possible?’

You already gave your opinion in a TED Talk in 2017. Has the war in Ukraine changed your opinion?

No. But TED Talks partly censored me. Peace is possible. But it’s not inevitable. That’s the part they edited and cut off.

Of course, it is hard to believe, even more so when Europe is experiencing war in Ukraine. How do you reach peace? Well, on my own I found all of the answers in the bahá’í religion.

It is not too different from Christianity and Islam. It shares the same values.

The difference in bahá’í is that it’s clearly explained. There are none of the parables or underlying and hidden messages of the Bible and the Koran. And there is a tool box to reach peace.

You left willing to learn new languages. What would you say to people who have trouble being understood if they do not speak the same language?

First things first. English is not spoken universally around the world.

Try your luck in the middle of Siberia and see the guy laughing. Communication is often the biggest hurdle.

I understood people through vibrations. I do not know how else to explain it.

You can try using gestures. The problem lies in that they frequently differ from country to country.

For example, when I asked for food in China, I put my fingers in front of my mouth and teeth. He thought I had toothache!

In Asia, you have to gesture by diving your hands into a bowl that you mimic with your other hand. These are some of the ways to ask for food.

The gesture for the number 10 is another killer.

I would show my hands with all of my fingers spread out. People thought I wanted to choke them.

The number 10 in China is indicated by manipulating your two index fingers in a certain way. There are sounds as well. When I mimicked a chicken to get an egg, I would get a chicken.

Let’s move on to the second phase of your travels…

My travel experiences were organised in two phases: from 1955 to 1973, then from 1975 to 2019. The way I travelled in the second phase was different.

I would take a plane from France to a country and then travel for seven to eight months. I wanted to see all of the countries I had not visited during the first phase of my travels. Once there,

I kept to the ‘one dollar a day’ motto.

I was even more motivated in this second phase, since I wanted to spread the bahá’í message around the world.

Bertolt Brecht once said that he who knows and does not do anything about it is a wrongdoer.

I have always tried to be honest and share what I know. People are free to believe me or not. At least I shared the message.

I did not travel to write books, but to learn and become richer from the inside. I am not a real traveller per se, but more like a student.

The second part of my globetrotting comprised three types of travels : those for pure discovery, those where I talked about the bahá’í faith and the ones where I did both.

In a previous interview you mentioned that you wanted to go to the Chagos Islands, one of the last territories you still had to visit. Did you make it?

Chagos is the greatest regret of my life.

The story behind the islands implicates France, Great Britain and the United States.

The United States installed a military base on Diego Garcia, the biggest island, to monitor the activities of the Soviet Union’s submarines patrolling in the Indian Ocean.

They had no right to build a military base, according to the laws enacted by the United Nations. The law specified that a country given independence should be offered the whole land. But the Americans kept their base.

In 1968, they ousted the population. These are the holier-than-thou people lecturing us all day long.

What happened there is a disgrace. The area is a secret military complex now.

I wanted to sail with an inhabitant of Mauritius and venture into the northern parts of the island where abandoned villages lie.

My contact was ready to take me on his boat in 1976 before his licence was suspended.

He was still not permitted to sail there in 2021 when I wrote to him, disheartened, to say that I was physically no longer able to travel.

People underestimate how much energy it requires. I stopped right before Covid struck. Is that not the sixth sense?

Related articles

‘We found balance between joy and frugality living off-grid in France’

Retired French soldier hunts down war grave thieves and Nazi relics

'We wanted a small bolthole but bought a ruined French chateau'