-

Profile: Dorothée - France's beloved TV icon and screen mum

Profile of the singer, actress and TV presenter who captivated millions of schoolchildren

-

What you should do to your garden in France in spring

Weeding, pruning, sowing, preparing the lawn…here is how to welcome sunnier days

-

Rules change for dog walking in France from April

Here is how to ensure you and your dog remain within the rules and avoid fines

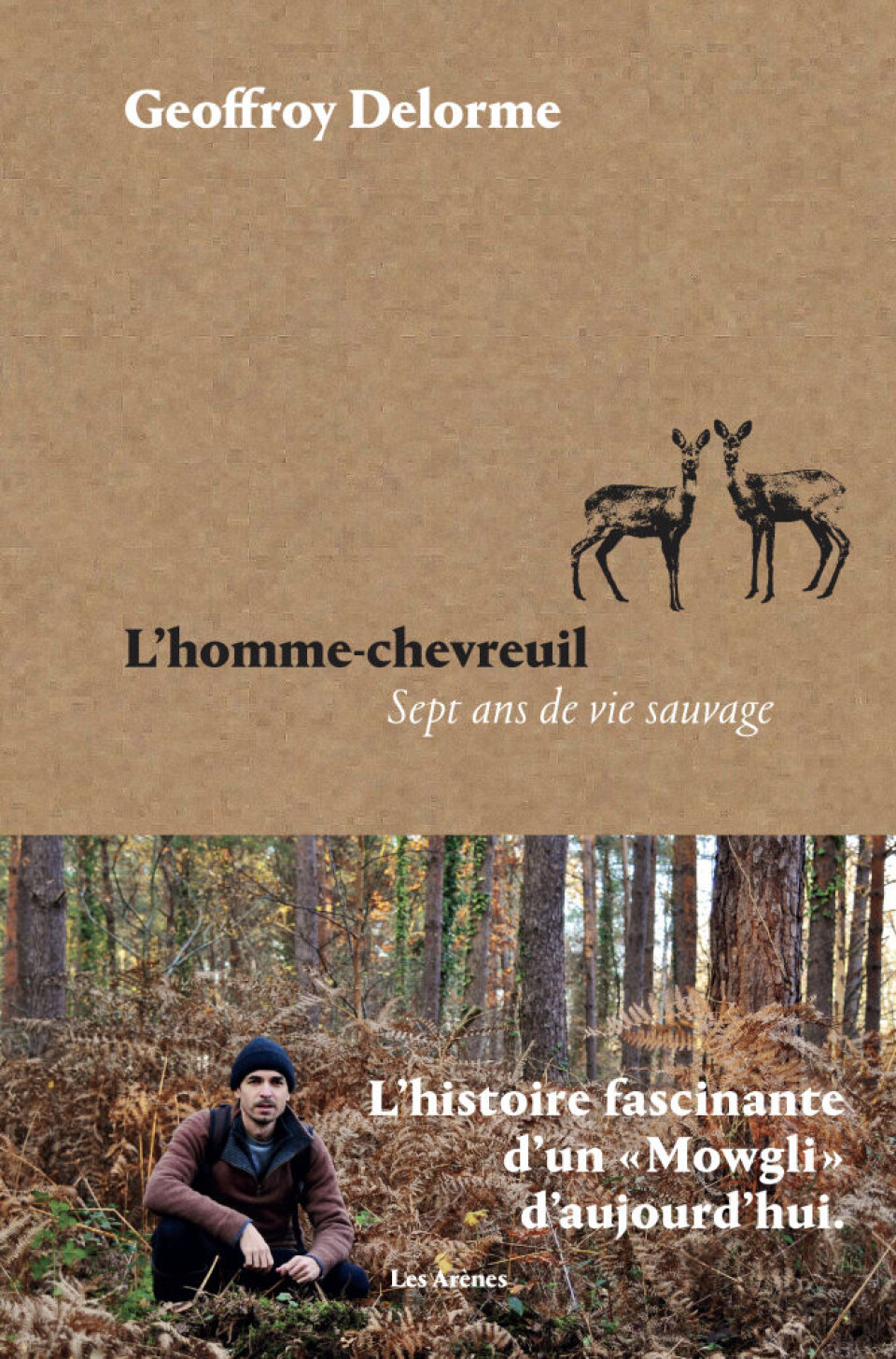

Meet the man who lived side by side with Normandy roe deer

Over seven years from when he was 19, Geoffroy Delorme developed an extraordinary relationship with the roe deer who lived in the forest near Louviers in Normandy

Chévi, Daguet, Prunelle, Courage, Magalie, Mef, Sipointe and many others became his companions and his friends and has written a book about his experiences, L’Homme-chevreuil-sept ans de vie sauvage.

What made you set out on this unusual adventure?

I was home-schooled when I was young and I did not have any friends and there were no pets.

The house where I grew up was at the edge of a forest. I did not know much about humans. The world I knew best was the woodland and the animals living in it.

First I would go at the end of the afternoon, then for a whole day, and then for a night until little by little I stayed for longer and longer periods.

On one occasion I stayed nearly a whole year in the forest. It takes time to learn how to live there, and to know which plants you can eat, which I would study in books back home.

Like a wild animal I began to create a territory to suit my basic needs with a wide variety of food in quantity and places where I could shelter.

It also took a long time to gain the confidence of the animals. The roe deer were not the only ones interested in me. There were also badgers and foxes. I did not have the same close relationship with them but in the end they tolerated me living in the forest.

Why did you choose roe deer?

I did not choose them, they chose me.

I would move around looking for different plants to eat and as I did so I met deer more and more frequently.

One, who I named Daguet, was more interested in me than the others. Each time we came across each other, he was increasingly curious.

He would still stay about 20 metres away, but gradually, it was as if we were playing a game together, the distances got smaller, until the day when we stood ten metres apart, motionless looking at each other and I knew I had the privilege to be accepted by him.

I imagine a roe deer in the forest will not make a friendship with another animal, so why with a human?

I think humans have an incredible capacity to attract all animals. It is perhaps a unique characteristic of our species. During the whole adventure I made friends with 43 different deer.

I had a strong relationship with about about twelve. There were another twenty I knew well and could walk behind, and there were others who would not be frightened and run away when I met them in the forest, though I never got very close to them. It depends on the character of the deer.

They are all different, a bit like us, in fact. We do not become friends with everyone just because we pass them in the street.

That is something you make very clear in your book, that the deer all have very different personalities.

They do and they tend to be similar within families.

Chévi, Courage and Sipointe came from the same family and they were all very curious. Mef, Magalie and the others in their family were more wary.

Did you have a favourite?

Chévi was my best friend. We had the same interests, and we liked having fun in the same way.

When I ate daisies, he would be right next to me, and we would have a game. He would push me with his muzzle to say there is a daisy, and I would do the same. We liked the same places.

Usually roe deer prefer to stay in the shade but Chévi liked to go to the edge of the forest where there was a little quarry and we would lie there in the sun together for four or five hours, and enjoy the day together. In that we really had something in common.

Is it like being with a dog? Can you compare your experience with that?

It is a much stronger relationship because a dog owner is the master and the dog is educated to conform to our rules.

But the deer were free to accept me or not and there was no question of one being dominant and the other subservient. We were in a form of partnership, sharing a part of our lives together, with a great deal of pleasure.

Roe deer are far more intelligent than dogs. They have a learning capacity which is incredible.

Have you made discoveries about roe deer that no-one else has ever made before?

At the time there were no books about roe deer in France. I depended on my own observations and learnt things which did not match with anything I read about.

Buttercups and other members of the ranunculus family are reputed to be poisonous and it was said no herbivore will eat them.

But roe deer adore them, and it allows them to purge their system of any parasites they might have caught over the winter period.

What did you discover about their behaviour?

They love to play, especially young females. Sometimes I could hardly believe my eyes.

I saw them run around and the one behind touched the hoof of the one in front who became the one who chases the others. They played the same kind of games as children, not very often, but perhaps three or four times a year when it was warm and sunny.

I also played the game with them when you see who can look into the eyes of the other the longest and they loved that. They like to be looked at.

Are they territorial?

Not in the same way as other animals.

In spring the females choose a territory with enough food to cover their nutritional needs for giving birth and feeding their fawns.

The males will choose a territory which covers several different female territories so they will have a choice during the rutting season. They are polygamous.

They do not live in herds, like the red deer, though they will live in small groups during the winter. This is the only time when they will choose a chief, who will be an older deer with experience who knows how to find food and protection from the cold. But this role will be shared and passed on from one to another. There is no real sense of leadership.

In spring, summer and autumn they are solitary living with their mate with their own territories but they live in the same way that we live in a block of flats.

There are shared parts where they come together but other parts where they are on their own, just like us. We live in groups during the day at work or at school, and in the evening we like to return to our home, to our close family.

How did you live in the forest? What did you eat?

To start with three quarters of my diet was plants and the rest tinned foot I brought with me. But when I stayed for months at a time I only ate plants from the wild.

You have to be organised. The basics have to be prepared in advance and gathered when they are around and I kept them in my bag to have supplies all year.

That could be acorns, chestnuts, hazelnuts and other fruits you can find on trees.

But aren’t acorns poisonous?

Raw acorns have tannins which can be toxic if you eat too many, but if you cook them two or three times in boiling water until the water is clear, the tannins are leached out and you can eat them safely.

Acorns were eaten regularly up to the Middle Ages until they were replaced as a staple by the arrival of the potato. They are rich in nutrients and were a source of proteins for me as well as other nuts. In complement I would collect nettles, daisies, dandelions, comfrey. In the spring I would make holes in birch trees and drink the sap, which was really revitalising, full of minerals. There are around 40 edible plants you can easily find in the wild.

Did you need to eat enormous quantities not to be hungry?

No. I ate little and often, about fourteen times a day. I adapted the way I lived over several months.

During the night, when it is coldest, I would keep active, because there was a risk of hypothermia if I slept too long. It is safer to sleep in the day when it is warmer.

Like the animals I slept for short periods – for example several times in 24 hours – and then woke up and enjoyed my time in the woods.

How did you protect yourself from the cold, because you did not have a tent or a permanent shelter?

You learn that the principal factors making you cold are wind and humidity.

When there was a storm I would go with the deer to a pine forest where there is less wind and return when the weather was better.

I had stocks of dry sticks hidden away so I could always make a fire or a temporary shelter if necessary.

I wore wool in different layers. Never cotton, because that just soaks up the humidity. Even if wool is wet you remain warm because the fibre is 80% air. I always had a needle and thread with me, and as soon as there was a hole I would mend it.

And to wash yourself?

I washed in places where rainwater collected in a bowl between two or three tree trunks.

There was also a cemetery near the forest with a tap I used, and river water. If I found water in the forest, I could filter it through a sock and then boil it to make sure it was safe to drink.

Was it difficult to finish the adventure?

I would have stayed longer, but a forestry company came in and cut down the trees and a road was built through my territory, destroying the food I depended on. So I had to leave.

Did that affect the deer as well?

Yes, they had to change their territories. We should learn to protect the forest and to share our lives with the natural world.

People complain that deer come into their gardens and eat their plants, but it is because their natural habitat is being destroyed. If they had enough to eat in the forest they would stay there.

The roe deer, were generous and shared their territory with me, even though it was not my natural habitat.

We can learn from them. We create a territory for ourselves and we do not let in other humans or animals.

In the forest different animals share the same territory. They live in an ongoing system of partnership.

Related stories

France's swallow population has fallen by 40% in the last 20 years

Edible flowers in France: Pansies for the plate is a growing market