-

France plans crackdown on fraud around obligatory energy ratings for homes

All homes being sold or let need an up-to-date DPE

-

AI finds ‘soaring’ cases of fraud in French home renovation applications

More than 40,000 cases were detected in 2024, the housing agency states

-

How much do energy efficiency renovations cost in France?

Owners will want to ensure properties improve by at least two DPE ratings, increasing the work and cost needed

Make sense of local rules governing planning permission around France

The Plan Local d’Urbanisme determines what can be built where, to what height, and, more importantly, what cannot be built - but only half of rural communes have one

Town planning issues can arouse strong passions in France – not least when it comes to the plan local d’urbanisme (PLU).

This document determines what can be built where, to what height, and, more importantly, what cannot be built.

Buildings are not its only remit – a PLU can turn agricultural land into a nature reserve, or determine that wetlands be drained for arable fields.

PLUs were introduced in 2000 with the expectation they would quickly cover the country, providing a coherent system of town and country planning that could be managed from Paris with minimal fuss.

In at least one Dordogne village shortly afterwards, a mayor was nearly lynched after rumours spread that a PLU was being prepared which would declare large parts of undeveloped land as being in a flood plain, and consequently nearly worthless.

Read more: Village in west France halves housing land prices to attract newcomers

Some 22 years later, around half of rural communes still do not have a PLU, or its less detailed cousin, a carte communale. Instead, planning permissions and decisions are based on national guidelines interpreted by departmental officials, who give their verdicts to the mayor.

The socialist Hollande government declared in 2016 that individual communes no longer needed their own PLUs. Instead, a PLU could be drawn up covering intercommunal groups (CDCs), called a PLUi, thus removing some pressure from municipal councillors in small communes.

After four years, most CDCs say they will have their PLUi ready by 2025, if all goes well.

It is an elaborate process involving recommendations from CDC officials who, although qualified with master’s degrees, often do not have any local knowledge or experience before getting the job. They run up against elected councillors who sometimes run rings around them.

After a draft plan is agreed, it is put out for public consultation. This can be the first time people realise the extent of changes envisaged for their commune, and often prompts multiple objections to the parts which affect them.

When the PLUi is eventually signed off by the inspectors holding the public inquiry, it goes for final approval to the CDC, and then gets sent to the prefect for state approval. Only after this does it become a legal document covering development for the commune.

Once in place, a PLU is in force until it is revised, with complete overhauls involving substantial change to the original vision being typically done around every 10 years.

Smaller modifications, such as changing the use designation of specific zones, can be done on decisions of mairies.

It is difficult to legally contest a PLU in place, but citizens may request to their mairie a change to the designation of the area where they live.

Mairies covered by a PLU or PLUi should provide access to it, either in the form of a chart book, showing each classified zone, or online – if the commune or CDC has a server capable of handling such detailed maps (many do not).

Maps are in a standard form, folded into eight in a chart book, and can be opened to see your land and nearby areas.

Unfortunately, digital maps seem to be based on clunky software from the 1990s, which is not user-friendly. Consider requesting a training session with someone familiar with it if planning to do detailed research.

If you have a new-build project, the PLU should let you know, before submitting a planning application, whether it fits with your commune’s vision.

All is not lost if it does not.

It is possible for a PLU to be changed after it has been approved – January’s Connexion story about plans to build a housing estate with aircraft hangars on land zoned as agricultural is an example.

For a PLU to be changed, it requires a vote from the municipal council or CDC concerned, which must then be approved by the prefect.

What was designed to be a simple document has become more complicated, but property owners wishing to keep house documents up to date should look for three elements in their local PLUs:

- The map extract showing the zone given to your land;

- The written rules for the commune relating to this zone;

- Any annexes which might affect your land.

The main ‘zone’ categories are ones that are already ‘urbanised’ (shown by a U), zones which can be built on in the future (AU), agricultural land (A), and areas protected by virtue of their sensitive environmental nature (N).

In theory, since 2016, all PLUs should have three clear chapters responding to the following questions: Where can I build? What environmental factors must I take into account?

How can I be connected to electricity, water, telephone and sewerage systems?

The document must have an overall view of the area, including economic forecasts, desired population densities and details of infrastructure to meet these.

It must also have a projet d’aménagement et de développement durable, setting out general planning and transport objectives for the area. Green councils use this section to try to cut CO2 emissions.

A technical guide to the various laws, maps and annexes must also be provided.

One final point: if land you own is moved from being in a zone where construction is banned to one where it can be built on, as can happen when new PLUs are drawn up, make sure you declare capital gains when you sell it.

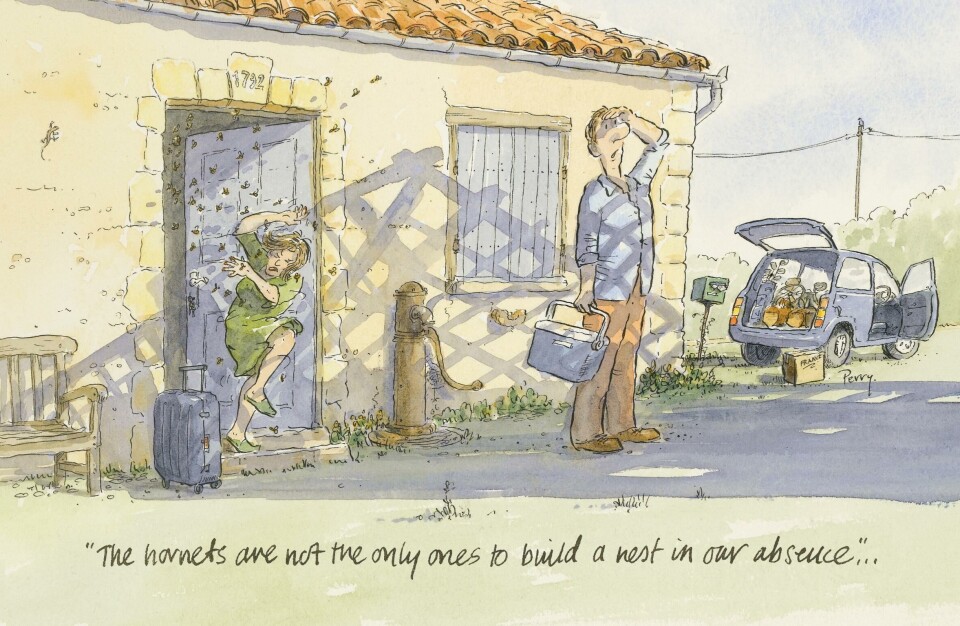

Our main image was drawn for The Connexion by artist Perry Taylor. For more of his work see www.perrytaylor.fr

Related stories:

How do we connect our French holiday home to public drainage?

Aerovillages project in France: Housing estate with planes in garage

Artisans in France must inform clients of planning permissions

Couple find solution to French second-home tax retention on house sale