-

From Cézanne to the Césars: four French art and culture recommendations

Impressionist masterpieces in Aix-en-Provence, a stylish Louvre exhibition, and a crime series to watch

-

Photos: Paris exhibition explores what people do alone at home

Behind the curtain: L’Intime Expo takes a fascinating look at people's private lives

-

French art gallery exhibits paintings made by a two-year-old

The abstract creations are being displayed until next week

Audrey Tautou moved to tell tale of artist hunted by Nazis in France

Actress has left semi-retirement to star in Paris show about painter Charlotte Salomon

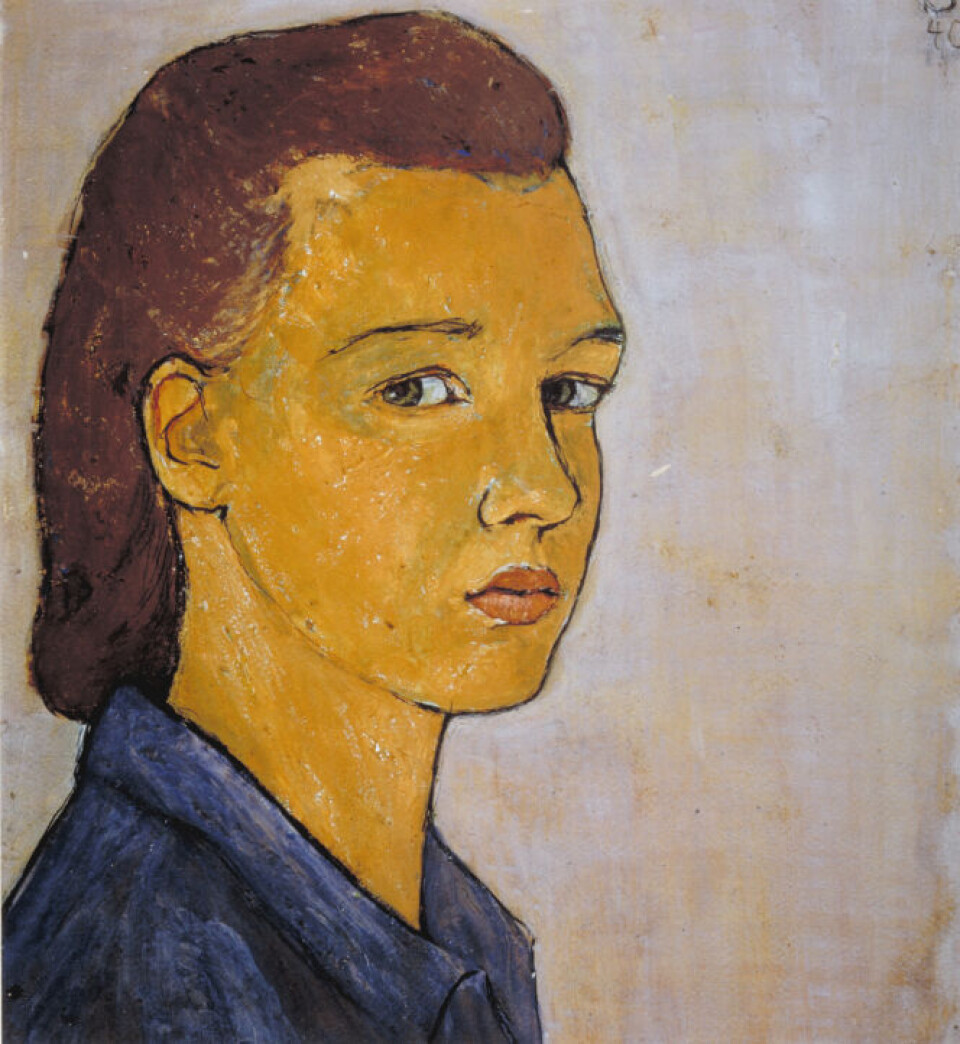

The story of a young German artist who moved to France before being deported and killed in Auschwitz has encouraged actress Audrey Tautou to leave semi-retirement for an intimate performance at a Paris theatre.

Tautou is alone on stage as she narrates the life of Charlotte Salomon, accompanied only by a musician and projected images at the theatre La Seine Musicale.

Tickets for the final performances this week are still on sale.

Tautou told L’Obs: “The artist is so beautiful, her work so strong. And it’s essential to speak of Nazism, of deportation, of which she was a victim. That’s why I accepted this adventure, which is completely new for me.”

The play’s text has been reworked by French writer David Foenkinos, with whom Tautou, 47, has worked previously, from his 2014 novel Charlotte.

Charlotte Salomon’s story

Born in 1917 to a Berlin doctor and nurse, Charlotte suffered tragedy when her mother died when she was eight.

She later began art studies but after the Kristallnacht attacks on Jews in 1938, her father and stepmother fled to the Netherlands while she went to France to be with her grandparents.

They, and other Jewish refugees, had taken refuge at l’Ermitage, the villa of American millionaire Ottilie Moore, in Villefranche-sur-Mer, near Nice.

France soon became less safe: the Nazis occupied the north in 1940, then fully occupied the south in late 1942.

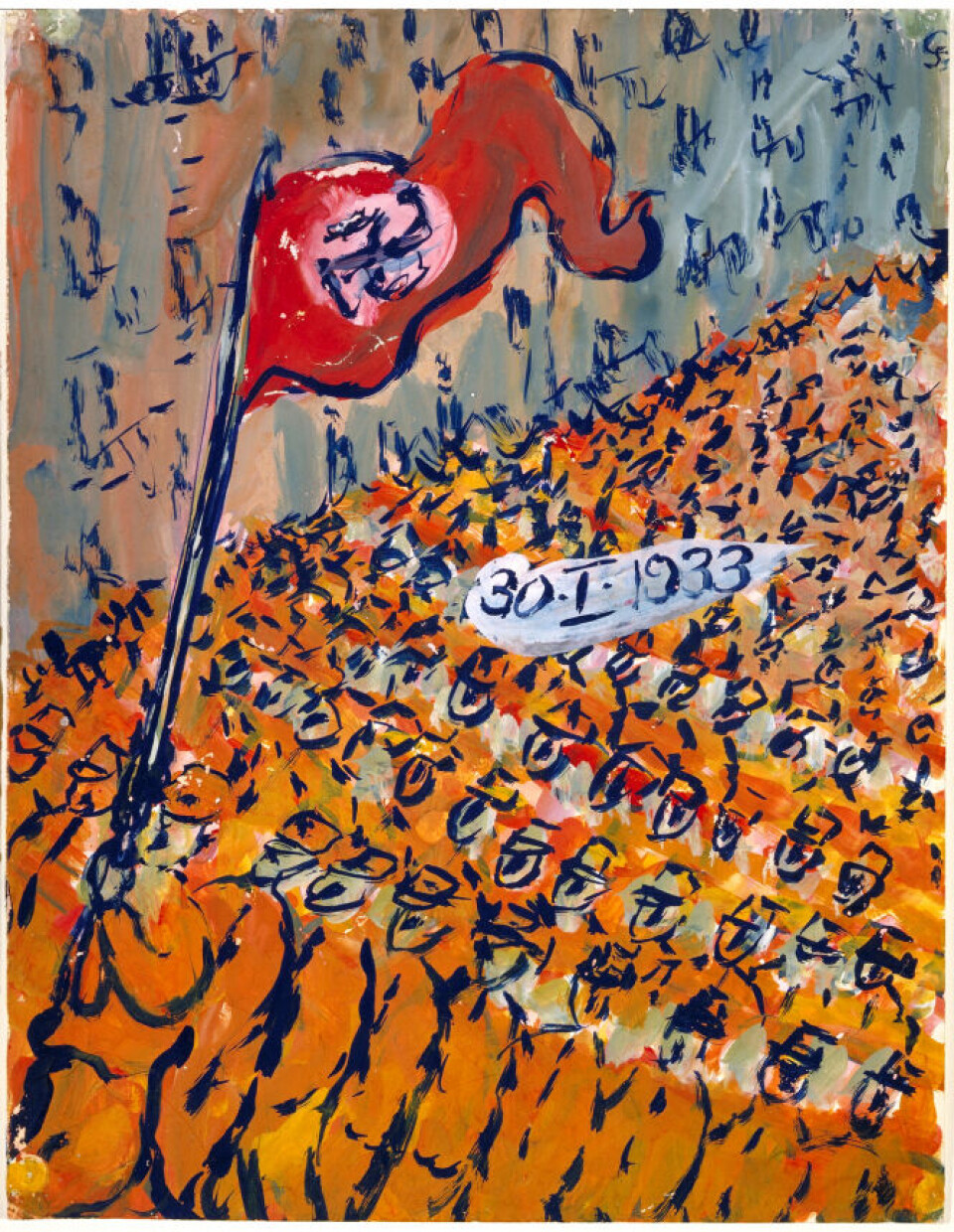

In the few years Charlotte spent on the Riviera, she made an outpouring of work, much of which became Life? or Theatre?, consisting of 769 pieces.

She asked a doctor friend to keep the works for Mrs Moore, who had returned to the US, taking several Jewish children with her. “Keep this safe, it is my whole life,” she said.

It combines images and texts inspired by her and her family’s lives (however the names are changed).

Charlotte, who had recently married and was pregnant, was arrested with her fellow refugee husband by the Gestapo at L’Ermitage in September 1943.

They were deported to Drancy, outside Paris, and sent to Auschwitz. She was killed by gas after arrival, aged 26.

The doctor later passed the art to Mrs Moore who gave it to her parents.

They kept it for years, showing it only to the father of Anne Frank, who had asked if they thought his daughter’s diary was worth publishing. They published the art in turn, and organised an exhibition in 1961 and in 1971 donated it to the Jewish museum in Amsterdam

Family traumas

Charlotte, whose visa was linked to being her grandfather’s carer, suffered multiple family traumas in her short life.

Soon after joining her grandparents, she moved with them to Nice, where her grandmother died jumping from a window after the outbreak of war.

She had been told her mother died from flu but her grandfather later said she had also killed herself – as had her aunt and several other relatives. In one painting, he says to her: “Why don’t you go ahead and kill yourself?”

Charlotte and her grandfather were imprisoned briefly in a camp in the Pyrenees. Life? or Theatre? shows her crouching on the floor in a crowded train en route to the camp with him but she writes she would “rather have 10 more nights like this than a single one alone with him” – a reference to what is believed to have been sexual abuse. Elsewhere, she shows him asking her to “share a bed with me”, saying it is “natural”.

At one stage, she left him to paint in a hotel room on Cap Ferrat, but was obliged to go back due to visa issues.

She wrote: “To have gained insight into everything then have to return to take care of him… I was sick, I was constantly beet-red from mute rage and grief.”

She added that “my grandfather was the symbol for me of the people I had to resist… someone who had never felt true passion for anything”.

Shockingly, a confession text, only published in 2015, reveals she poisoned him with an omelette laced with drugs her grandmother had kept in case of the Nazis’ arrival. She says she watched him die and sketched the scene. Some commentators think the confession is also a work of art and mixes fact and fantasy but it is generally thought it was true.

‘I became my mother, my grandmother’

Some time earlier, Charlotte had spoken to her doctor friend of her anguish over her mother and grandmother. She said she found herself at a crossroads, wondering “whether to take my own life, or undertake something eccentric and mad”. Her friend encouraged her to put it all into her art.

“I will live for them all,” she wrote, referring to the women in her family. “I sat there by the sea and looked deep into the heart of humanity. I became my mother, my grandmother… I learned to travel all their paths.”

The powerful results evoke many themes, some dark and disturbing, others full of the light and beauty of southern France. The last image shows Charlotte in a swimming costume, looking at the sea as she sketches.

L’Ermitage no longer exists, but the nearby street bears its name and the mairie put up a plaque about Charlotte in 2015. She is not yet a household name, partly because her art is not sold on the open art market.

However, retellings of her story are becoming more common, including a 2021 animation, voiced by Keira Knightley and in French by Marion Cotillard.

Related articles

Last survivor of French war massacre village Oradour-sur-Glane dies

Varian Fry: The American who was a ‘Schindler in France’

182,000 march against antisemitism across France