-

Attention au chien! New map helps walkers avoid guard dogs

Discover how MapPatou helps hikers and joggers in France avoid potentially dangerous guard dogs

-

Discover the fascinating world of peregrine falcons and modern falconry

Explore the majestic bird's nesting habits and the evolution of falconry, from ancient traditions to modern-day racing and breeding practices

-

Classic French recipe with an exotic twist: caramelised onion soup

A dish inspired by the travels of two Paris chefs

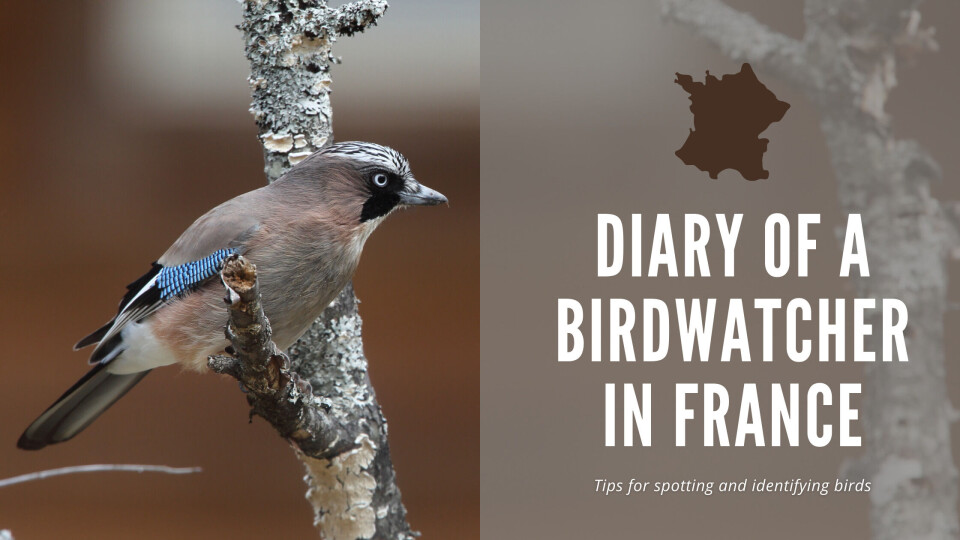

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: The Eurasian jay

They are found all over France, wherever there are oak woodlands

As I stepped out of the mill where I live one morning I was shocked to hear our old cat mewling high above my head in the tallest oak tree that lords over our front garden.

It was a very particular miaow, unmistakably hers; what was she doing up there?

Peering up through the tangle of branches I eventually found her, or rather him, an Eurasian jay (Geai des Chênes in French).

These birds are known to be mimics, and this one really had captured my cat’s voice perfectly.

I hear one one of these Eurasian Jay’s every morning that does an imperfect rendering of a buzzard’s mew. It is thought that mimicry is to impress a mate so it could be that it is a young bird still learning its repertoire.

Dressed in muted harlequin colours they are beautiful, especially the pale blue and black feathering on the bend of the wing.

I pick up these feathers on the ground and they are lovely, delicate like a butterfly’s wing.

The body is mainly cinnamon colouring, with black and white highlights, with a handsome moustache.

But their cries are far from beautiful: a mixture of loud, hoarse and scratchy rasps, often heard in flight.

They can be quarrelsome too. One spring there were five of them racketing away in a fractious group in a constantly shifting circle around the mill for about 10 minutes, no doubt a territorial dispute.

Being resident they are always there, and one possibility could be that the juvenile birds from the year before were being driven off to establish their own territory.

We are surrounded by oak trees, there are plenty of nest boxes and feeders so the population of songbirds is high, and as jays supplement their diet in summer with raids on nests for eggs and chicks, it is a rich habitat, worth squabbling over.

When they want to be silent they can be. Looking out of an upstairs window I saw two scruffy punky heads peering over the edge of a large twiggy nest in an oak tree not five meters away, above the terrace where we eat.

So I watched, and found a jay stealthily fluttering from branch to branch. It would pause, clearly checking us for a reaction, before sneaking back to its precious young. The pair had successfully raised a family unseen and unheard all Spring without us knowing.

The Eurasian jay is a member of the Corvid family that includes ravens, crows and magpies, who are recognized by ornithologists to be the most intelligent of all birds.

Corvids are able to recognise researchers on a crowded campus that captured and released them several years before – and pass that information on to their offspring; work out how to make of tools by bending wire to reach treats; and, wonderfully, dropping walnuts on Japanese pedestrian crossings, waiting for the lights to change, and then hopping out to pick up the pieces from the nuts opened by passing tires.

Eurasian jays can be found throughout France, a bird of the countryside anywhere that there are oak woodlands. Not exactly shy, but mistrustful and wary of humans after centuries of persecution.

As is evident from their French name it is a bird that is intimately linked with the oak tree, le chêne. They form a relationship with the trees with the birds feeding from them and also helping them to grow.

Each jay can collect about five thousand acorns a year as they fall from the tree in autumn, selecting the largest and best to carry away. They take and bury them for winter food, sometimes up to several kilometres from the parent tree.

Oaks saplings do not germinate well in a woodland setting, they are not shade tolerant. To grow successfully they need open areas, fields and woodland fringes. So, out of that wide distribution, inevitably the jays forget a small percentage, and the acorn is left to grow into a tree.

Oak trees provide a food source for many species of animal.

Edible dormice, loir or lérot in French, eat both acorns and beech mast.

When we first moved into our home in Aude, there was a healthy population of loir sleeping away in the walls: they hibernate in winter for six or seven months.

When they wake up in May they can be noisy at night, and are considered a pest as they can damage electric cables and cause fires.

One evening I found our cat sitting by the loo with a certain glint in her eye, and, looking in, there was a damp dormouse staring up at me.

We fished him out, dried him, and carried him to a nearby wood.

Rescue done, or so I thought. However, do not make the same mistake I made as these animals have an excellent homing instinct.

I caught one in a trap and again carried it off into the woods in the night. The next night I caught the same one, recognisable by a nick out of its ear. It probably scampered back to the house quicker than I did! You need to take them a couple of kilometres away before release.

They are called edible dormice as Romans would trap them in the autumn when they are fattest and keep them in pits, feeding them a mixture of nuts to fatten them further, and then stuff and roast them. They are still eaten to this day in Croatia and Slovenia.

Loir are found throughout France, except on the Atlantic coast, but are not common. If you are really bothered by rodent infestation poison is absolutely the last resort, the victims enter the food chain and can cause the accidental death of other animals and birds.

Humane traps work well. Try and use them early in the year so that the loir can re-establish a territory, eat enough to fatten up before autumn and their long hibernation.

So, the mighty oak tree, source of food and home to many species of bird, mammal and insects, one of the best quality timber trees for construction and furniture is dependent on the services of a bird to continue its dominance in the French landscape.

Incidentally, over 1,000 of the most beautiful oak trees in France have been chosen to help in the reconstruction of Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris.

Jonathan Kemp moved to France in 1989 and lives in the department of Aude. He has been volunteering with the French nature association the Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux (LPO) for the past 20 years, working on a variety of different projects.