-

Know your cheeses and their seasons: which to eat in France in February

Cow’s milk cheeses dominate as winter comes to an end

-

Films and series to watch in February to improve your French

Every month we outline good film and TV series to improve your language

-

Duck Cold! Four French phrases to use when it is freezing outside

France's current cold spell is set to continue for the next few days - we remind you of French expressions to use to describe the drop in temperature

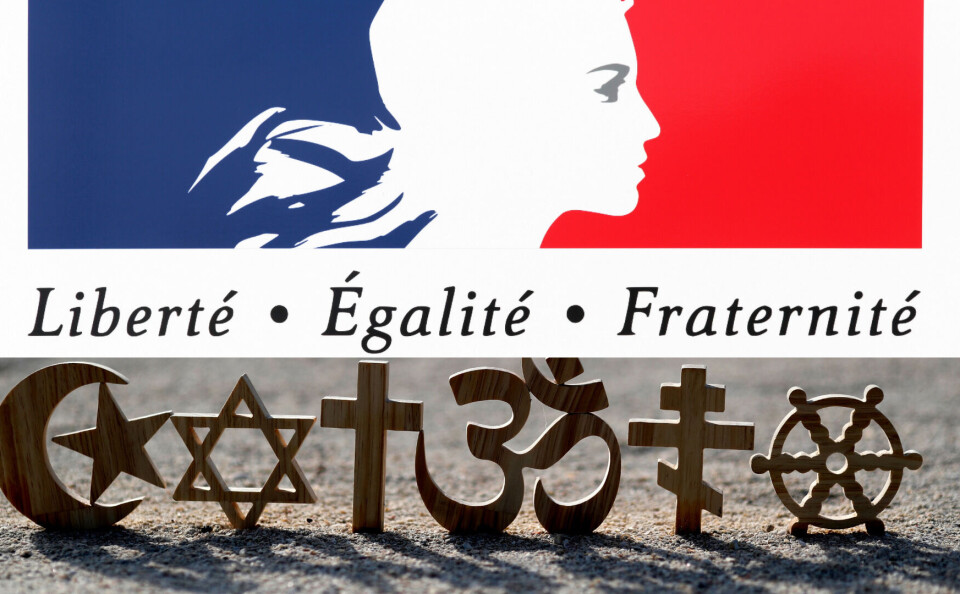

Laïcité: a bedrock of modern France

The importance of a secular state is seen as a key French value - but it can cause controversy, as Jacqueline Karp explains

DO YOU have a Boulevard Aristide-Briand near you? Or do you send your child to school in a Jules-Ferry or a lycée Émile Combes? If so, you are already familiar with key names in the construction of the French Republic.

Between them, these three politicians were responsible for free state schooling, obligatory education for girls and the rock of state neutrality towards religion on which la République is built: the principle of laïcité.

The term is very much part of the regular news cycle in France, with much of the debate today surrounding its influence over the Muslim community, and to the perceived challenges Islam presents to this element of the Constitution.

Left and Right politicians often unite to initiate laws to protect laïcité. Once the source of conflict with the Catholic Right over private education funding, the principle, an important element in the integration process, regularly generates ill feeling these days among extremist sectors of the Muslim community. That is why, a century after the original 1905 law, several new laws have been passed to protect it.

First, a few explanations. Laïcité does not translate well. Secularity is close but confusing. Laïcité is not easy to define either. It has evolved over two centuries and is evolving still. The concept was born of the Revolution, which guaranteed freedom of conscience to all and first separated State and Church.

Napoleon backtracked, signing a concordat with the Vatican in 1801 that was to poison Church-State relations during the 19th century and put laïcité on the back burner for much of it. (For historical reasons, this concordat still applies in Alsace and Moselle.)

Having been suppressed by the Vichy régime (along with liberté, égalité, fraternité – without which laïcité could not function), the principle was cast in the constitution of the Fourth Republic in 1946 – the State is indivisible, laïc, democratic and social – and remains firmly in that of today’s Fifth.

To understand the concept is to go a long way towards understanding the French. Maybe it could be defined as their permanent search for a delicate balance between sharing what they all hold in common, the Republic, and catering for diversity.

It is the principle that protects both personal and collective liberty and, as such, is the responsibility of both State and citizen. The indivisibility of the State is the State’s refusal to recognise any religious or ethnic community. France is one. There are two major dates in the history of laïcité: 1881 and 1905. In 1881-82, Minister of Education Jules Ferry decreed school to be “publique, gratuite et laïque” – state-run, free and non-clerical.

Teaching in French to a national programme provided children, whatever their linguistic background or beliefs, with the theoretical possibility of equal opportunity.

It created a framework in which adults could bring no pressure to bear on pupils to adhere to any philosophy, religion or political idea. That remains the basis of the French educational system today.

The 1905 law, engineered by Émile Combes and Aristide Briand, enforced the neutrality of the State and State institutions through the separation of the Churches and the State. Since that date, the State recognises no religion and therefore cannot directly fund any either.

If the same law grants the individual total liberty and privacy regarding beliefs, there is one condition: they must not disturb public order.

Given the repeated trauma that religion has caused in France’s recent history – from the Wars of Religion to the expulsion of the Huguenots and the Dreyfus affair – this means no proselytising and nothing that could be remotely interpreted as such.

It also explains why, in France, religious belief is far more than a private matter. Things spiritual belong to the realm of intimacy. It is extremely unusual to see anyone wearing any conspicuous religious symbol in public. To do so is perceived as a deliberate act, a message to others.

It is unthinkable to ask someone what their religion is and most people will be frankly embarrassed by anyone saying what theirs is. When, in 2003, then Minister of Interior Nicolas Sarkozy publicly announced the appointment of France’s “first Muslim prefect” he sent shockwaves throughout the land.

Knowing this helps in understanding intense French reaction to women wearing veils and abayas. It is seen not only as an unacceptable way of bringing religion into the public sphere, but also a form of peer pressure on other girls to do the same. Which takes us back to Jules Ferry and neutrality in the classroom.

This insistence on the privacy of beliefs was of course also reinforced after World War II by the fate of France’s Jews under the Vichy regime, and the obligation to publicly show their religion by wearing the yellow star. As a result of the trauma of State responsibility in their deportation and extermination, no statistics may be made regarding people’s religious beliefs, ethnic origin or colour.

All citizens are not only equal, but remain neutral in the eyes of the State.

The mosque debate

The 1905 law was finally well accepted by both Catholic and Protestant churches in France, who benefited financially when the State handed existing buildings and their costly maintenance over to local authorities. But the State cannot fund new religious buildings.

Hence the mosque-building debate and recent legislation allowing local authorities to contribute. For with generous donations from Saudi Arabia and Muslim foundations abroad pouring in, the inherent risk of encouraging fundamentalist movements to develop in France is obvious.

But the State cannot finance religious education either. The impasse has been paradoxically circumvented by the Catholic University offering courses, and Algerian imams due to work in France being trained in French and laïcité at the government-funded Institut Français in Algiers.

Conspicuous symbols and full-face veils

Amidst the religious tension following September 11 2001, and a number of potentially inflammatory cases in which some schools were confronted with Muslim girls wearing Islamic headscarves, legislation was passed in 2004 banning the wearing of any conspicuous religious symbol or sign in state schools. Never specifically aimed at the Muslim community (kippas, large crosses and Sikh turbans fall under the same category), the new law, despite fears it would be perceived as discriminatory and arouse further reaction, had the almost immediate effect of calming the situation, though some veiled Muslim girls and turbaned Sikhs found their way to private schools.

But the 2004 ruling legislated solely for public schools, not privately run establishments. In March 2015, Fatima Afif, an employee dismissed in 2008 from the privately run Baby Loup crèche in the Yvelines for refusing to remove her headscarf, won on appeal for “wrongful dismissal on the grounds of religious discrimination”.

The tense situation persisted in France through the 2010s and the Sarkozy presidency saw frequent flashpoints. In late July 2013, a police officer in the town of Trappes stopped a fully veiled young women for an ID check in the middle of Ramadan, he did not know he was unleashing days of rioting. But Cassandra, 22, was not infringing any law on laïcité. This time it was the one against covering the face in the public sphere, put into effect by the Sarkozy government in 2011.

Introduced ostensibly as anti-terrorism legislation, many felt its real purpose was more “anti-veil.” In fact, the number of women in France wearing the niqab is extremely small, and the number of women fined likewise.

Positive Laïcité

France’s politicians tried to calm the debate by sweetening the laicité pill with adjectives. Sarkozy invented “laïcité positive”, in which the government took into account the existence of religious groups in France.

He created a representative Muslim council, through which to address the Muslim community in France. Representative of only a portion of France’s Muslims, many of whom are non-practising, it has created more problems than it has solved.

The Hollande government coined “laïcité apaisée”, a low-profile approach in which negotiation would replace legislation as the best way of winning over those who regard the principle with suspicion.

True laïcistes believe the principle cannot survive any moderating tags. It must exist alone.

‘Traditional Laïcité’

The Macron government has backtracked on modernising laicité, “I am in favour of laicité as defined by the law of 1905, which protects us and allows us to believe or not believe,” he posted on Facebook, affirming that "it's 1905, nothing but the law of 1905".

How the principle of laïcité is applied today

NICOLAS Cadène, chairman from 2013 to 2021 of the Observatoire de la Laïcité, a committee set up by President Holland, spoke to The Connexion.

Can you define this difficult concept for our readers?

Laïcité is a principle which allows us all to live together. It is not a ban on religion or religious practices. On the contrary, it guarantees believers and non-believers alike the freedom to express themselves, to practise or not to practise a religion as they choose, on condition that public order is not disturbed. The State adopts an attitude of total impartiality towards citizens, who are all equal in the eyes of the State.

Do the current religious bank holidays not favour one religious group?

Christian festivals have, for the majority, become traditional holidays with little religious significance. Still, the State does not want to be seen as favouring one religion over another. In 1905, there was no Muslim population. But I don’t think this poses a real problem. Employees can use their RTT (recuperation of unpaid overtime in the form of days off) as they wish. The Stasi Commission (set up by President Jacques Chirac in 2003) went a long way towards identifying issues in the workplace. We shall build on that.

The conspicuous religious symbols ban was seen as directed only at women. Is that not a form of discrimination?

If people set out to present themselves in a way which is obviously a proselytising or a provocative attitude, that is not acceptable. It is not so much what people wear or their physical appearance, as the reason behind the choice. This is one of the subjects we shall be working on.

Islam has no clerical hierarchy. Isn’t the laïcité legislation trying to apply to individuals a law aimed at an institution? Doesn’t the 1905 law need to be adapted?

Not at all. The principle enables us all to live together. But, of course, we must avoid situations in which one group feels stigmatised by the law. That is one of our major subjects of reflexion. But there is no question of adapting the principle to new circumstances. It is one of bringing people to understand that laïcité is not a ban on religious practice but a system of personal freedom and helping them to adapt to the principle.

There has been talk in the press over banning the Islamic headscarf at university. [The full-face veil is already banned anywhere in public].

The State has a duty to protect minors from any form of ideological persuasion, hence the headscarf ban in schools. University is a world of adults. But the Republic has a duty to protect its citizens against the dangers of extremism. Some people attribute to laïcité powers it simply does not have. There is an urgent need for strong political action, at state and local level, in order to resolve the many problems the threat of extremism has brought to certain sectors of society.

The Observatoire has published its first report, a history and background to the concept. What else has it achieved?

We helped draw up two important documents: the ‘laicité charter’ and the syllabus for non-religious morality for schools. Both take effect this year. In addition, our report has pinpointed situations needing close attention in public administrations and local authorities (non-Metropolitan France included), as well as in the private sector.

How do you see your work developing?

We need a better definition of laïcité that reiterates the State’s position of neutrality and is more clearly understood by all, in France and at an international level. We are drawing up guidelines for the application of laïcité and religious practice in the workplace, and in the wake of the Baby Loup issue [see main article], for pre-school structures. We must show people how to react to situations. Overreaction is one of the major problems we face, when so much could be achieved by negotiation and taking things calmly.