-

Exploring Pont-Croix: officially named as France’s best tourism village

A Breton gem boasting strong cultural heritage, charming architecture and vibrant local life

-

Reading recommendations: books about France in English

A frank Parisian memoir, a humorous language-hacks how-to guide, and a Champagne-themed historical novel

-

Bergerac, Sarlat-la-Canéda and more picture-postcard Dordogne gems

Enjoy wine tastings, historic tours, and the vibrant Fest'Oie Goose Fair in these charming towns

Support your local community in France with a guidebook in English

A blog can offer a great insight into your town or village but why not expand it to benefit the local community too? Michael Delahaye explains how

Michelin, Fodor’s, Eyewitness, Lonely Planet... French cities and towns are well served by English Language guidebooks.

On a smaller scale, you might find English guides to many of the 162 plus beaux villages de France.

What about those places that are less than plus beaux, yet still rich in history? A guide in French, perhaps… but in English? Seldom. Who better to fill that gap than an English-speaking inhabitant? You.

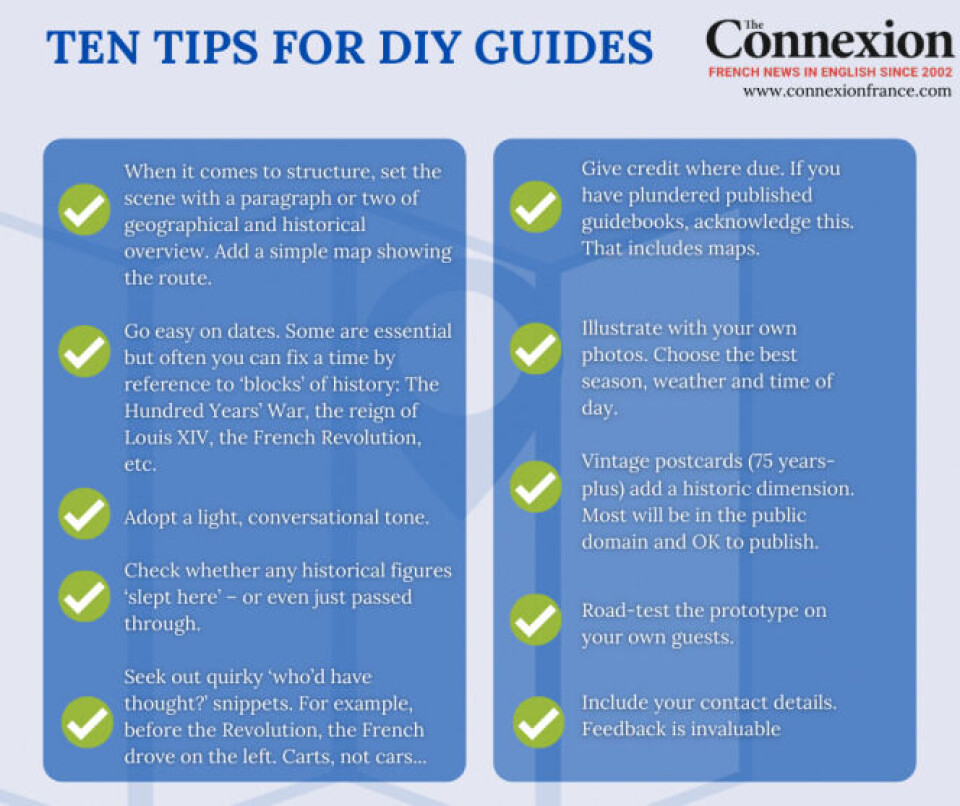

The guide can be as basic or as comprehensive as you wish. At the simplest level, it is amazing how much can be crammed into a single A4 sheet, printed on both sides and concertina-folded to form a six-page leaflet.

If you want to maximise your readership, go digital and create a website. Not just a guide, but a ‘community resource’, which your mairie and local businesses with English-speaking clientele, such as hotels and estate agents, will be keen to recommend and link to from their own ebsites.

If you already write a blog powered by the likes of WordPress, it is a fairly straightforward exercise to customise and rebrand it.

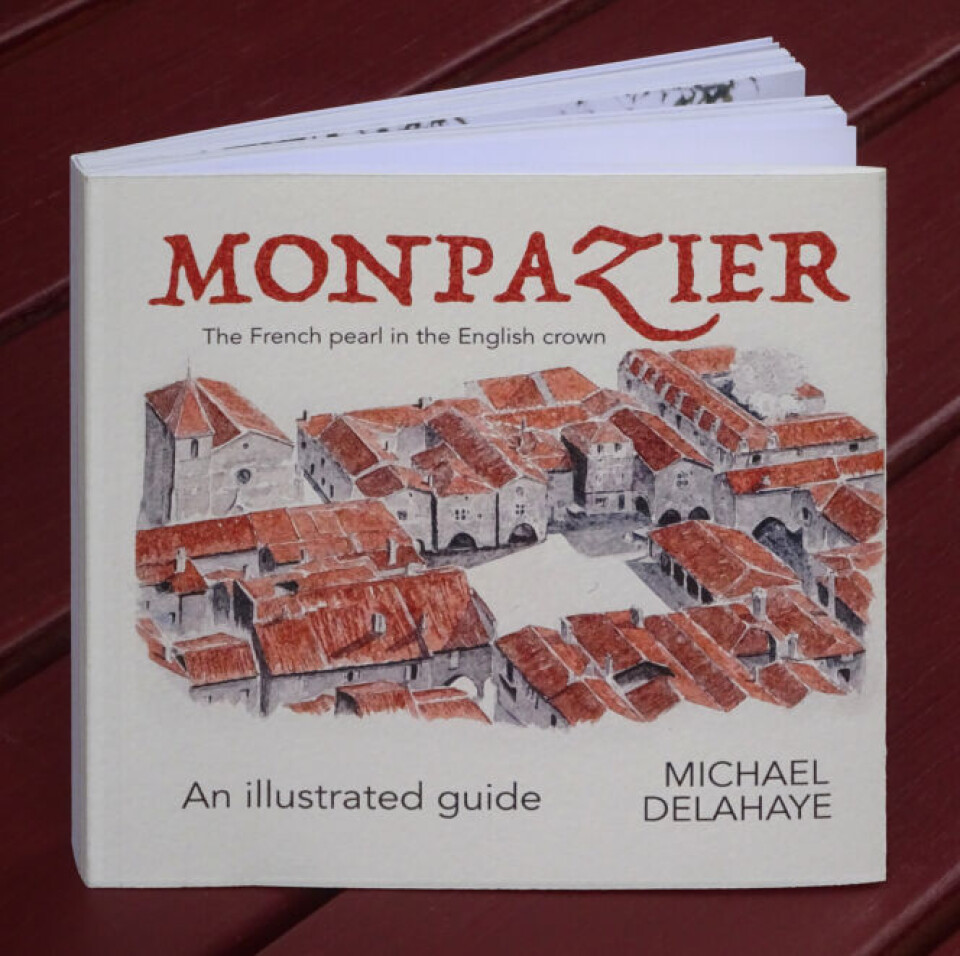

Get it right and you could move to the next level and create a proper walkabout guidebook! Thanks to advances in self-publishing, such as Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing system, this is now entirely feasible.

You can order hard copies of your ebook on demand, as many or as few as you want. So, no storage issues – and no complaints from your partner about that pallet of print taking up half the bedroom.

Alternatively, be bold and go solo.

Rather than using a third party, commission a local printer and become your own publisher.

This method is particularly recommended if you want to illustrate your guide. By opting for ‘offset’ printing, the more copies you order, the lower the unit price.

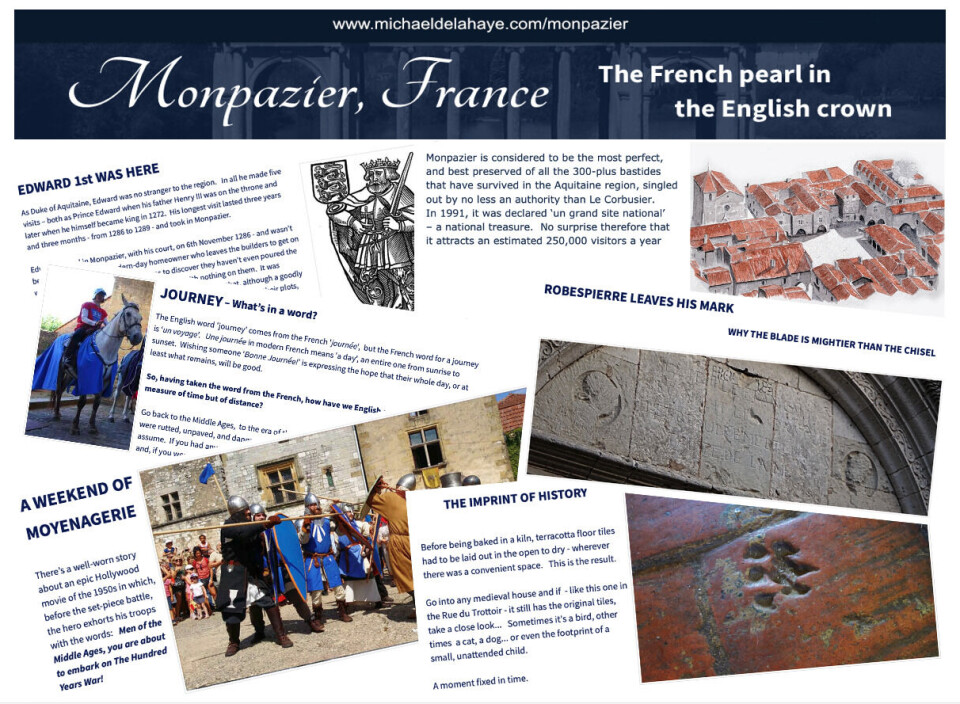

My own publishing dreams began with a website devoted to the history of my adopted medieval village, Monpazier in Dordogne.

All that was required, I told myself, was to find a printing firm and, using standard publishing software, convert my web pages into a format with which they could work.

Et voilà! Book out there, punters queuing, money rolling in…

Read more:France’s cultural and natural variety makes it a tourist hotspot

The early stages were encouraging.

Having got two quotes – one from a company in the UK, the other from a local French printer – I opted for the latter for reasons of cost and logistics.

The figures looked good. The guide would be 100 pages (50 leaves), measure 15cm x 15cm, and feature lots of photos. We even did a mock-up.

The total cost for a run of 1,000 came out at just under €3 a copy.

Checking tourism offices and bookshops, I concluded that €10 was the maximum most visitors would fork out for a local guide. On these figures, about two-thirds of the cover price would be pure profit after factoring in TVA and incidentals. I was starting to think like a drug dealer – the more so when faced with the next challenge: selling it.

On paper, it makes financial sense if you, the author, sell direct to the public. With no iddle-man, you can pocket all the profit. In practice, this means loading up the car, driving to a market or book fair, and spending the next six hours behind a pile of your oeuvre, adopting a posture of alert approachability that stays the right side of retail aggression.

I am full of admiration for those who do it. Flogging wine is child’s play by comparison – at least you can offer punters a glug before buying (and have the odd one yourself). But a book?

“Perhaps, madame, I might read you a sample chapter?”

As for ‘dipping in’, it is noticeable how reluctant punters are to leaf through a book in front of the author.

In a bookshop they can hide both selves and reaction but, standing before a stall, they will glance at the front, skim the back, and then sidle off like disoriented crabs.

The alternative is to find, and pay, someone else to do the selling for you. Local shops, cafes, bars, campsites, guesthouses and tourism offices are good places to start, proposing a share of the profits for their efforts.

At this point, I was fortunate to have a well-qualified neighbour to mentor me.

Brian McPhee is an author who came to writing after a career in IT marketing.

He suggested that, as an inducement, I should offer potential outlets a customised frontispiece or wraparound advertising their business. And (later perhaps) why not double the market by doing a parallel text version in English and French?

It was just the sort of savvy, left-field thinking I needed.

I settled on a wholesale price of €6 a copy, giving my pushers – sorry, sellers – a generous €4 mark-up if they sold it at the recommended €10. That would leave me with a profit of €3 a copy: half what I would get selling direct, but still offering a good chance of recouping my investment.

I hit gold with my first cold call.

The biggest hotel in the village thought a complimentary guidebook would offer its guests a more useful welcome than the traditional bottle of wine. In anticipation of publication, they agreed to take 100 copies, with the confident expectation of repeat orders. Best of all, they would pay up front. Could it really be this easy?

The short answer is ‘no’. Just as I was about to metaphorically push the print button, I discovered that upfront payment is the exception.

Read more:‘Peach walls’ of Paris suburb offer glimpse of its horticultural past

More common is an insistence on a sale-or-return arrangement: “We will display your guide, take the punters’ money and settle up at regular intervals to split the proceeds.”

To collect your share, you will have to do regular trawls of all your outlets, like a member of a mendicant order or, worse, a rent collector.

Expect the inevitable excuses for why you have picked a bad moment, with exhortations to come back next week instead.

I knew my limitations in terms of both time and patience, and ultimately decided that the website was as much as I could handle. I would stay virtual, non-profit, purely recreational. So much for ‘breaking bad’.

The mock-up of the book still sits on my office shelf in silent rebuke.

You should not be deterred by my wimpishness, however.

A guide, whether virtual or physical, can be a great way to increase your involvement in the community and contribute to its life and economy. If you have an entrepreneurial flair and some spare cash to risk, you might even turn a profit.

A final tip: do not be afraid to play the ‘public service’ card. By stressing it, you might persuade your mairie to underwrite part of the initial outlay. As an inducement (again, mentor Brian’s invaluable advice), offer to donate a small percentage of every sale to a good cause, such as the restoration of the village fountain.

Alternatively, or simultaneously, the tourist office might well agree to act as your main outlet for no cut – if only to give a positive response to that all-too-frequent question: “Avez-vous un guide... en anglais?”

Related stories:

The Pyrenees village where Napoléon III and Victor Hugo went to bathe