-

How we set up a seniors' club in the south-west of France

Richard and Patricia Romain, both 76, moved from Kent, UK, in 2013 and now live near Carcassonne in Aude

-

I became a published psychic medium after moving to France

Reader Claudia Amendola Alzraa, 37, explains how she found her calling

-

Nine face suspended prison sentences for online attacks targeting Brigitte Macron

Defence lawyers deny that the accused acted as a ‘mob’. Mrs Macron’s daughter says the campaign badly affected her mother

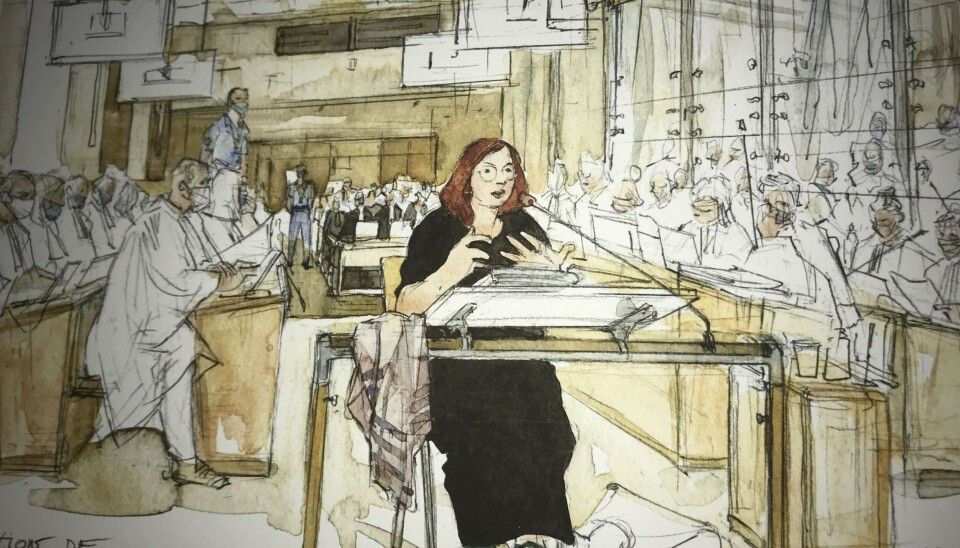

‘I drew in five minutes the absolute pain of a lifetime’

Retired courtroom artist shares her many years of experience covering France’s most memorable and harrowing trials

Noëlle Herrenschmidt is the grandmother every child wishes they had. No doubt they loved the unique Christmas gifts she stacked in binders for them all, containing drawings of her house in Seaux where they like to play.

But Ms Herrenschmidt, 82, is also a source of inspiration to journalists, reporters, and all kinds of artists.

Her late-flowering career is a reminder of how journalism and art can sometimes intersect.

She became a “watercolour reporter” after covering Klaus Barbie’s trial in Lyon in 1987, a German Nazi tried for crimes against humanity for the part he played in the Holocaust.

She drew the accused, survivors and judges at the trial for French newspaper La Croix.

She then covered more trials of WW2 Nazi collaborators, such as Paul Touvier (1994) or Maurice Papon (1997).

She also visited hospitals, the highest institutions in France, the Vatican, and covered the notorious Clearstream trial in 2009, each time dressed in the black, 18-pocket jacket that holds her artist’s materials.

Her drawings appear in various books, often featuring the words of Antoine Garapon, a French magistrate and, until 2020, the Secretary General of the Institut des Hautes Etudes sur la Justice (IHEJ).

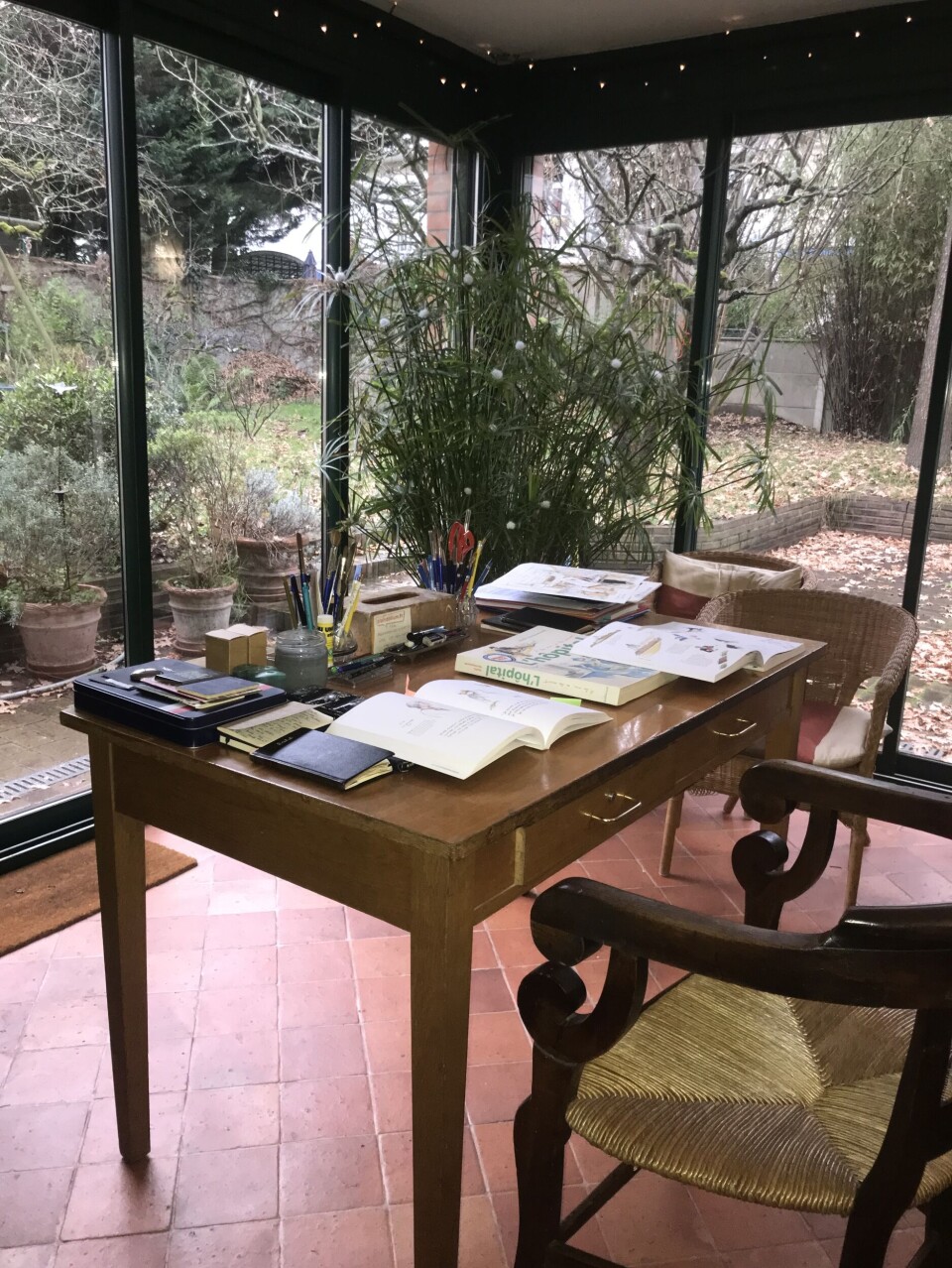

“When my work touches the lives of others, I am like a fish swimming in the sea. I was put on earth for that,” she said during our interview in her workshop, where the walls were covered with her drawings, and cabinets contained the fruits of her whole career.

The Connexion met her as a new retiree, six months after she had finished covering the trial for the 13 November 2015 Paris terrorist attacks.

During the interview she took drawings out of cabinets and pointed at images on the walls as questions about her career unfolded.

Her workshop is a visual statement of a reporter convinced that there is humanity in all of us.

Covering the 13 November terrorist attack trial was your final project before retiring. Was it the most sensational, moving, or important trial of your life?

I am often asked this question. There is no such thing as ‘most’ anything. Klaus Barbie’s trial was equally moving because it took 30 years for the survivors to provide testimonies, with all the anger and sadness that time had contained.

The biggest difference in the Paris trial was in the relative closeness in ages of the victims to the accused, and the relatively short timespan between the attack and the trial, hence the extraordinary emotion.

But I have spent my whole career navigating these heightened emotions. Every trial is exceptional in terms of the emotions it incites.

Read more: November 13 Paris attacks trial: Life sentence but not for 130 deaths

How do you shoulder what seems to be a burden?

This is another one often asked. Being a court artist is all about transmitting words and emotions from people.

There are no limits to what we can draw, or to the emotions we can absorb. I simply transcribe what I feel.

This is an aspect of myself that speaks and expresses itself. I often say that I am the spokeswoman of victims, lawyers and magistrates.

What are your main memories from the 13 November trial?

It was all incredible. Firstly, because of its length, and secondly because of the atmosphere between everyone who attended.

There was a feeling of benevolence thanks to the location itself, which had been specifically designed by architects to be peaceful, and due to the fact that the policemen wore a lighter blue than the dark blue uniform they usually wear.

There was a sort of a community that built up, an atmosphere that I had never felt before at other trials.

Families’ testimonies were harrowing, and sometimes lasted a whole day.

The hardest moment was during Yolande’s testimony, when she spoke about her twin daughters.

[Shows drawing] See this drawing for example. I made it in five minutes. Nothing else is needed to understand what is happening. This is what I do, and from which I take the most pleasure.

I drew in five minutes the absolute pain of a lifetime. This is all of my life.

Read more: Paris terror attacks survivor: Remember the victims, not their killers

You are said to have struggled drawing Salah Abdeslam, the only surviving terrorist. Why?

He has a complex, terrible and multi-layered personality. His face can change between childlike and hate-filled. Every court artist has had the same problem.

He is young, and we all had difficulties not drawing him older than he is.

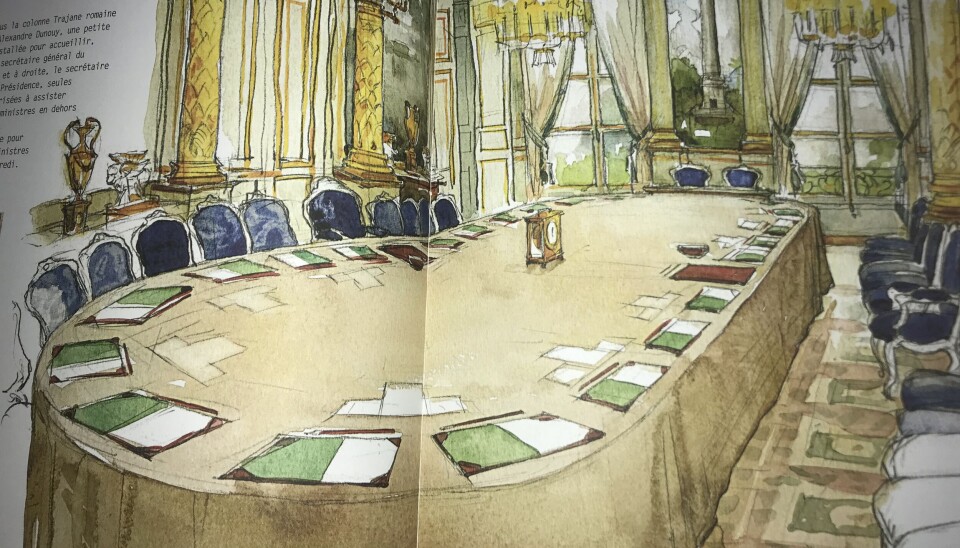

Do you find yourself adapting to the situation depending on the trial?

[Shows another drawing]. See this one for example. Here I drew the court architecture. I love large drawings and I wanted to capture the scale of the space.

And here comes judge Isabelle Panou, and she starts to speak. I thought it was the only thing that mattered.

She had such a vocal presence and power. I stopped everything for her.

This is what is fascinating about this job. You have to go with the flow.

Do you always need text to accompany your drawings?

I could never get to the bottom of a trial without the words of the magistrate or judge to expand on what I draw.

Juger le 13 novembre is a book that asks people to go the extra mile.

I hope it will be useful to young people, because it gives them an insight into the workings of a trial.

You have covered the trials of Maurice Papon, Klaus Barbie and Paul Touvier. Isn’t it harder to give humanity to people who have committed inhumane crimes?

I only have to listen and watch. There is no ‘give’ when you face someone like Barbie for example, who was cold, impenetrable, and undaunted.

I sat next to him. Then magistrate Pierre Truche stood to ask him: “If your children were to ask you about what you have done, how would you react?”

I drew a ‘two-second Barbie’, as I like to say. After two seconds, his expression returned to the Barbie the audience had known for ten months.

But during those first two seconds, I saw a moved human being, the human being behind the monster. Because Barbie is a monster. Papon, on the other hand, maintained the same expression during the whole eight months of the trial.

I do not ask myself questions when I draw. I watch, and listen, with my pen in my hand. Like with Yolande. A trial is like a play. You know bits of the story, you know the order in which the characters appear. But you never know the final act.

Has your view of people changed after covering trials, prisons, hospitals, or the Vatican?

I have learned everything from being in prisons, particularly that literally anyone can fall into it. There is no such thing as ‘bad guys’ and ‘us’.

They are not only killers. But also, you do not leave prison the same person you came in as.

I have slept in cells. I always sleep where I report because you cannot understand a location fully if you have not slept there. You hear the sounds, the blanket that scratches.

That was in 1997, and you can probably imagine what it is like nowadays.

I have drawn the circle of life in hospitals. I learned to resist power at the Vatican, a very violent power that says no out loud.

In my inner self, I thought: yes, I have to get behind closed doors.

But it demands considerable energy and diplomacy. People are the same wherever and whoever they are.

Read more: France’s Catholic ‘influencers’ find new audience online

How were you able to get so many doors opened by so many different institutions and trades?

My greatest skill is my ignorance. I am not here to be seen, but to pass on information and to transmit emotions. I have always been like that wherever I go.

For my book Les coulisses de la loi (The corridors of power) I followed senators for six years by being discrete, dressed in black, and listening to people. Doors opened one by one, slowly.

I asked what it is like to be a senator, an MP, what their daily lives are like. Some politicians uncovered touching revelations, the danger of power for example.

My books are meant to be educational, to help us understand our institutions. I am a student transcribing what I have learned.

Why watercolour?

Have you seen my paintbox? It is tiny, light, it bothers no one and allows me to talk to people while drawing.

The story is that the watercolourist Frédéric Houssin looked at my Barbie drawings and said: “And where is the colour?”

The very next day, I went out to buy some watercolours.

While preparing for this interview, you told me about an ongoing project with the United States’ justice system.

I was first asked to visit Chicago’s court in 2004, where I witnessed extraordinary violence in a monstrously dirty and segregated environment, with white judges lined up to sentence only black people.

The highlight of the trip was that I was asked to draw women waiting for judgement, in the basement downstairs.

It was so dirty, with all these women sat there like they were cattle waiting to be butchered.

This is the only time in my life when I drew from memory and not on site.

Years later, former Supreme Court judge Stephen Breyer, who had read Les coulisses de la loi, asked me to visit Boston’s court.

Here, I saw the opposite to Chicago – a marvellous environment dedicated to the people, offering shelter to the homeless and a kindergarten for children.

Now that you are retired, you draw villas for people. Would you accept commissions from our readers to draw their houses?

I only draw now if I am paid very generously. I have reached an age where I have decided to make some money from my art. This is how I want to spend the next ten years of my life.

I think I have squared the circle with the justice system and institutions.

See more of Noëlle Herrenschmidt’s work on her website.

Related articles

Career change in France: Paris attack made me reflect on what I wanted

Sempé was a master illustrator but also a sociologist, say cartoonists

Simon Beck: The artist reveals the secrets of his snowshoe drawings