-

Photos: 94 chateaux open their doors to visitors in Dordogne

The fifth Chateaux en Fête festival offers a chance to look around many impressive properties that are usually private

-

Ballet lessons bring health benefits to over-55s in France

Online classes with the Silver Swans are transforming lives of older adults

-

Profile: Dorothée - France's beloved TV icon and screen mum

Profile of the singer, actress and TV presenter who captivated millions of schoolchildren

Joséphine Bonaparte, Napoleon’s wife, was nothing if not a survivor

Her life was far from ordinary: she lost her first husband to the guillotine, built up legendary debts and wild animals roamed freely about her extensive gardens

Joséphine Bonaparte (1763-1814) was born into a wealthy family in Martinique. Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie grew up on a sugar plantation which was decimated by hurricanes when she was just three years old.

In 1777, to repair the family’s fortunes, her younger sister Catherine-Désirée, who was only 12, was engaged to marry Alexandre de Beauharnais. But when she died, 16 year-old Joséphine took her place, and embarked for France.

She and Alexandre married in 1779 and the marriage produced two children; Eugène (1781-1824) and Hortense (1783-1837) - who later married Napoléon’s brother Louis - but the union was not a happy one. Alexandre abandoned his family, had multiple affairs and visited prostitutes, eventually resulting in a legal separation during which Joséphine lived at a convent, the Abbaye de Penthemont in Paris.

Finally in 1794, during the Reign of Terror, Alexandre was arrested and thrown into jail. A month later, Joséphine was also arrested. Separated from her children, she corresponded with them via notes hidden in the laundry, until this was discovered and stopped. She remained in jail until a week after her husband went to the guillotine in 1794.

When she was released, a widow of 31 with two children to establish in the world, Joséphine managed to recuperate her husband’s possessions, and then embarked on a series of advantageous love affairs with leading political figures. She played up to the prejudiced view that women from Martinique were lazy, sensuous and capricious, but historians generally agree that she was ruled by her head more than her heart, and perhaps her own experiences had taught her to keep an eye on the bottom line. In 1795, at the age of 32 she met Napoléon Bonaparte who was six years her junior, and he at least fell passionately in love.

His famous letters include the declaration, “I awake full of you. Your image and the memory of last night’s intoxicating pleasures has left no rest to my senses.” Her letters were much cooler, but they were married the following March, in 1796. It was at this point that she adopted her second name Joséphine instead of Rose, and also dropped the name de Beauharnais in favour of her second husband’s surname.

Napoléon’s family were not impressed with the marriage. Not only was Joséphine an older woman and widow with two children, but she was sophisticated, elegant and aristocratic, making them feel clumsy in comparison. Two days after the wedding, Napoléon left to lead the army into Italy. He wrote passionate love letters, but she rarely responded and when she did her tone was often less than loving.

Painting 'Joséphine in coronation costume' by François Gérard. Pic: Baron François Gérard

With the benefit of hindsight, it seems foolish that in her husband’s absence she plunged into an affair with Hippolyte Charles, a handsome Hussar. When Napoléon heard about it, he was furious and in 1799, in Egypt with the army, he started his own affair with the wife of a junior officer. His letters became noticeably less passionate, and although Joséphine apparently didn’t have any other romantic liaisons, he went on to have several other mistresses, although there was never any question of him leaving his wife. “Power is my mistress,” he said, in 1804.

In December 1800, Joséphine was almost assassinated in a Royalist bomb attack designed to kill her husband as the royal party went to the opera. She survived yet again. Napoléon was in the first carriage, and she was in the second when a bomb planted in a cart exploded.

In 1804, Napoléon was elected Emperor of the French, making Joséphine the Empress, with her own court. When she caught him in bed with her lady-in-waiting Elizabeth-de-Vaudey, she was furious and in the ensuing row he threatened to divorce her for not producing children. The marriage was patched up by Hortense, and after the coronation, Joséphine took over the household which had belonged to the Queen before the revolution.

The pressure to produce a male heir to inherit Bonaparte’s crown was intense however. It seemed for a while as if a solution had been found when Hortense married Napoléon’s younger brother Louis, and produced Josephine’s grandson Napoléon Charles Bonaparte, who was duly declared heir to the throne. But the problem re-appeared when the child died of croup in 1807. Eventually, in 1810 Napoléon divorced Joséphine in order to marry Marie-Louis of Austria who he hoped would give him an heir.

Joséphine understood the stakes, and remained close to her ex-husband. For his part, Napoléon declared, “it is a womb that I am marrying” and insisted, “it is my will that she [Joséphine] retain the rank and title of Empress, and especially that she never doubt my sentiments, and that she ever hold me as her best and dearest friend”.

Joséphine went to live in the Château de Malmaison, near Paris, where she cultivated her famous rose garden and collected art. She became a serious patron of the arts, working closely with sculptors, painters and interior decorators to develop her unique Consular and Empire style at the Château de Malmaison. She was also a leading art collector.

Joséphine cultivated her famous rose garden in Château de Malmaison. Pic: Kiev.Victor / Shutterstock

She didn’t stint a penny on her refurbishments. In fact her spending and debts were legendary. French Empire design from that period is Neo-Classical opulence and splendour taking inspiration for symbols and ornaments from the ancient Greek and Roman Empires. Symmetry is very important, antique heads with identical curls falling to the shoulder, figures of Victory, with identical rosettes or flowing tunics.

Napoléon’s emblems included the eagle, the bee, stars and the initials I (for Imperator) and N (for Napoléon). Figures of Victory were plentifully used, along with palm branches, Greek dancers, nude and draped women, antique chariots, horses, wild beasts, grape vines and thin trailing ribbons.

In terms of architecture, the Arc de Triomphe in Paris is probably the best known example. Interiors were styled with huge rooms richly decorated and featuring Corinthian pilasters and vertical panels with ornamented ceilings.

Château de Malmaison was also equipped with a heated orangerie large enough for 300 pineapple plants. Another greenhouse was heated by a dozen coal-burning stoves. She grew more than 250 varieties of roses, and the gardens were home to all sorts of animals running wild, including kangaroos, emus, black swans, zebras, sheep, gazelles, ostriches, chamois, and a seal.

In 1811 Marie-Louise gave birth to Napoléon II thus securing the line of succession. In the event, he died of TB at the age of 21 and the title passed to Napoléon III, son of Hortense Beauharnais and Napoléon’s younger brother, Louis Bonaparte. But during his lifetime, Napoléon believed he had produced the all-important heir to the throne.

As Joséphine was creating extraordinary interiors and lavish gardens, Napoléon was conducting the Napoleonic Wars, which he lost conclusively in 1814. The victorious Allied powers forced him to abdicate, and exiled him to Elba, 12 miles off the coast of Tuscany, Italy, His wife Marie-Louise took refuge in Austria with their son.

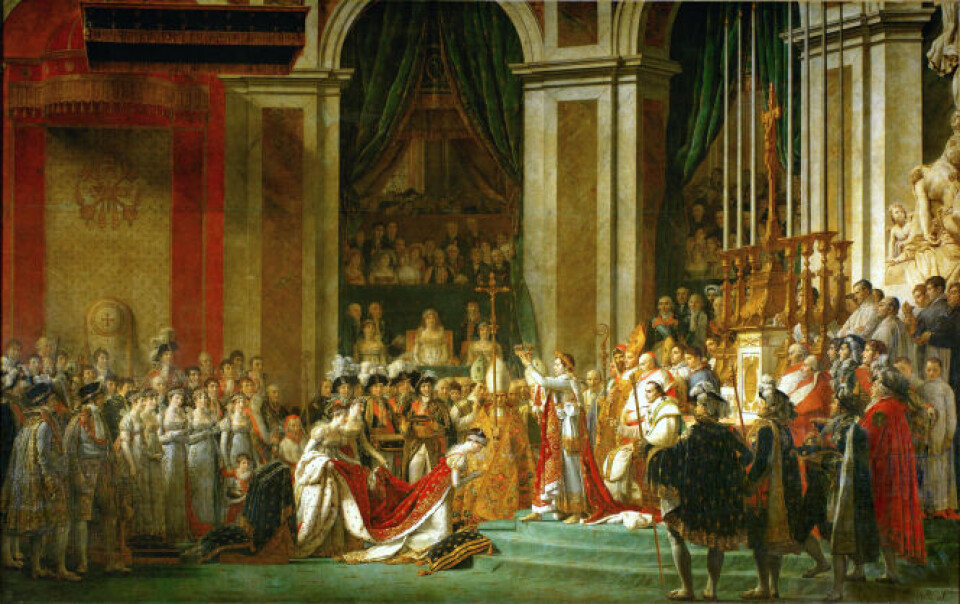

Painting 'The Coronation of Napoleon (1807)' by Jacques-Louis David. Pic: Jacques-Louis David

Joséphine however asked to join Napoléon in exile. The request was refused, and she died shortly afterwards of pneumonia at Malmaison. She was 50 years old. She was buried in Saint-Pierre-Saint-Paul churchyard in Rueil-Malmaison. (Her daughter Hortense is buried nearby.)

Napoléon read about her death in the news and was devastated. He escaped from Elba in 1815 to embark upon the ill-fated invasion of Belgium which culminated in the Battle of Waterloo after which he was exiled once again, this time to Saint-Helena in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

He died there in 1821, his last words reportedly being: “France, the Army, the Head of the Army, Joséphine!”

Josephine Bonaparte was the grandmother of Napoléon III and the Brazilian empress Amélie of Leuchtenberg (Eugène’s daughter), and her descendants include members of the royal families of Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, and Norway.

The Château de Malmaison was mostly uninhabited after Joséphine’s death, gradually ransacked and vandalised. The gardens were destroyed in a battle in 1870. In 1842, it was bought by Maria Christina, the widow of King Ferdinand VII of Spain. She sold it to Napoléon III in 1861. It was fully restored in the early 20th century and is now open for the general public to visit.

Related articles

Schadenfreude, secret envy: Why do the French love the British royals?

Anne de Bretagne: A symbol from birth of a ‘free’ Brittany

Did you know? French monarchs and emperors were exiled