-

Photos: 94 chateaux open their doors to visitors in Dordogne

The fifth Chateaux en Fête festival offers a chance to look around many impressive properties that are usually private

-

Ballet lessons bring health benefits to over-55s in France

Online classes with the Silver Swans are transforming lives of older adults

-

Profile: Dorothée - France's beloved TV icon and screen mum

Profile of the singer, actress and TV presenter who captivated millions of schoolchildren

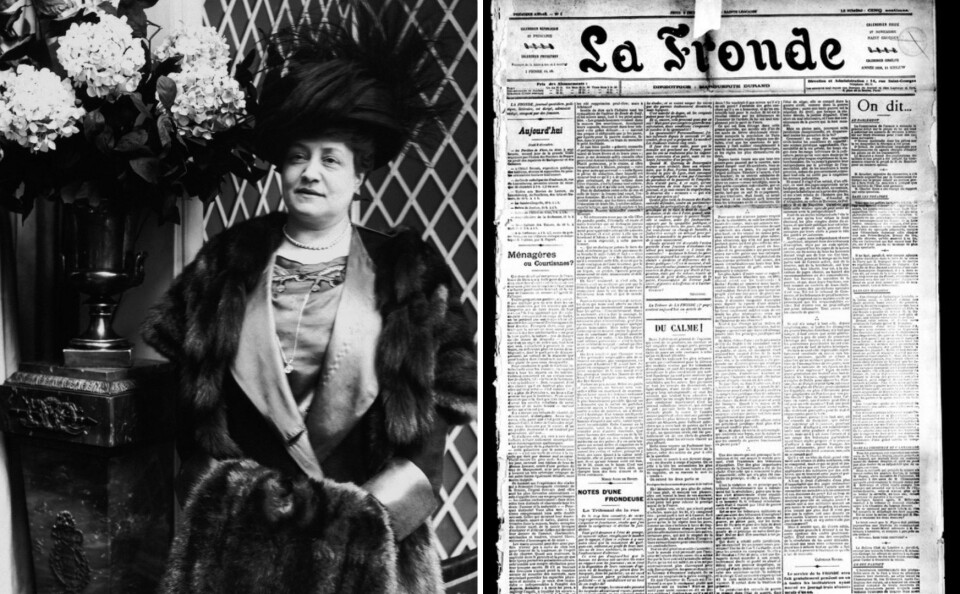

Marguerite Durand: the force of France’s first feminist journalist

The 19th-century former actress founded a daily newspaper written and produced entirely by women

Marguerite Durand’s life (1864-1936) straddled a period of dramatic change.

When she was born, Napoleon III was in power, the American Civil War was ongoing, and women did not have careers.

By the time she died, women were establishing themselves in all sorts of professions. This was partly as a result of the loss of young men during WWI and partly due to women like Marguerite Durand, who did so much to liberate women from nurseries and kitchens.

Journalism was a way for a woman to contribute to public life

Born in Paris, she was educated at a convent and in 1879 (aged 15), won a place at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse. This was not a conventional choice for a well brought up young lady from a middle-class family.

She received good marks, and after graduating she joined the Comédie-Française, playing a variety of ‘innocent young girl’ roles.

She left in 1888 to marry a lawyer and politician called Georges Laguerre. Her husband was a great supporter of a movement led by the political mover and shaker Georges Boulanger.

This entry into the world of politics and journalism led Marguerite Durand to begin writing articles for the press. It was a way for a woman to contribute to public life, and to have a voice in the world.

“Marguerite Durand was a woman aware of the power of her beauty,” says historian Mary Louise Roberts.

“She knew she could walk into a room and turn the heads of well-known men. At the same time, she suffered from the reputation most actresses garnered, of being readily ‘available’ as mistresses or prostitutes. She wanted respectability and middle-class status.”

Photo: Marguerite Durand begin writing articles for the press to have a voice in the world; Credit: Archive PL / Alamy

She refused to write negative articles on feminist event

After Boulanger committed suicide in 1891, she turned away from Boulangisme, and left her husband.

She began working at Le Figaro, writing a column called Courrier (Post).

She divorced her husband in 1895 (divorce had been legalised in 1885), and a year later in August 1896, gave birth to her son Jacques, whose father, Antonin Périvier, was one of the directors of Le Figaro.

Evidently their relationship was not harmonious, because records show that Périvier took the almost-newborn baby from his mother, forcing her to ask the Republican politician Georges Clemenceau for legal help in order to recover her son.

She was by this time a committed feminist, having been sent to cover the 1896 International Feminist Congress in Paris, where she refused to write the negative articles her editor had requested.

“I was struck by the logic of their arguments,” she said in 1935. “Their [the feminists] struggle was justified.”

Read more: Exhibition honours Paris suffragettes and women’s fight for equality

Every job at La Fronde was done by women

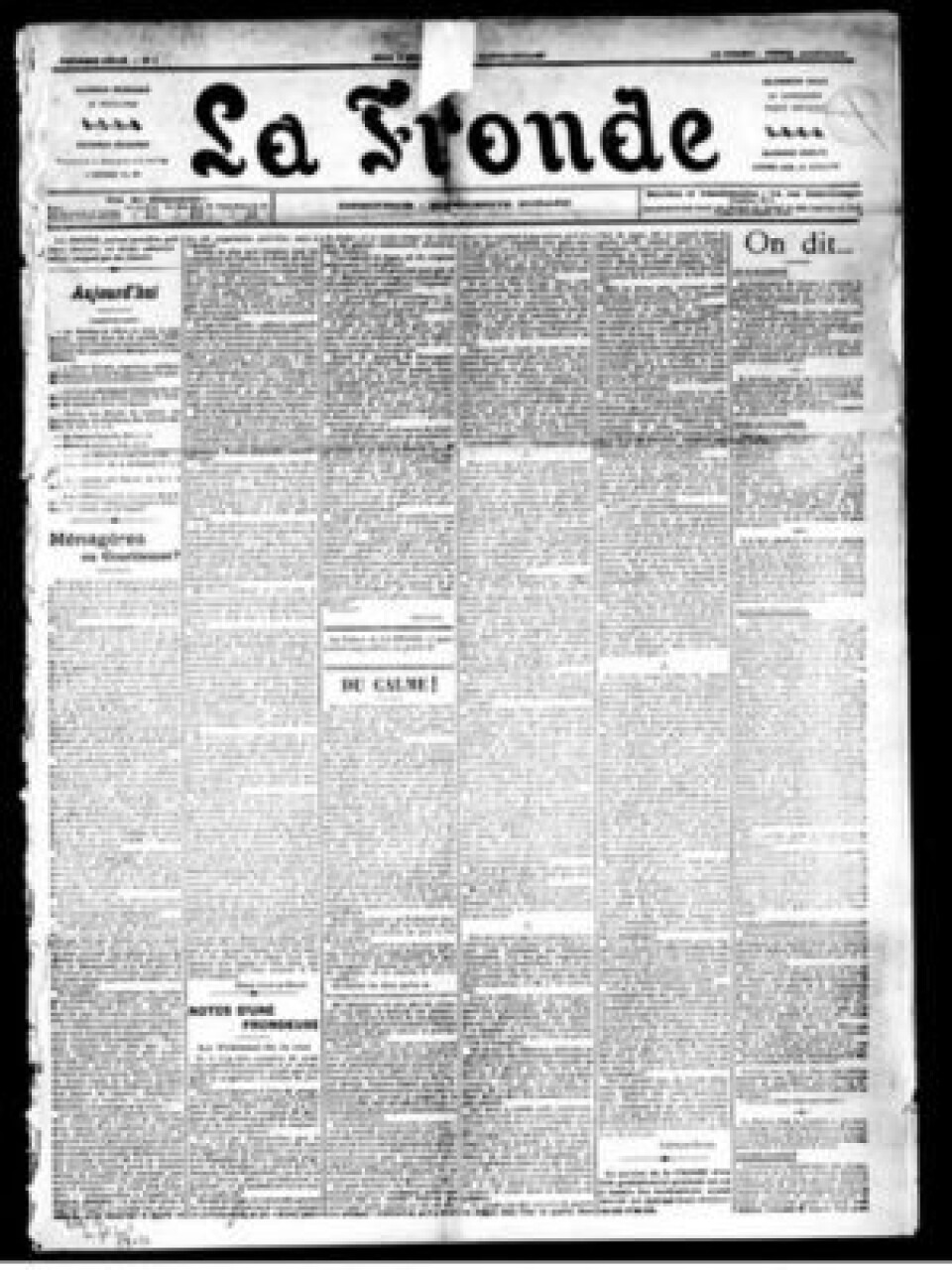

She described how she had the idea to give women a weapon, a publication which would affirm their abilities, not only dealing with feminist issues, but enabling them to become professional journalists. The publication would be called La Fronde.

Marguerite left Le Figaro, and the first edition of La Fronde appeared in September 1897.

Everything, from reporting to type-setting, had been done by women. The articles dealt with general news including politics, literature, sport, finance, and the Dreyfus Affair. (The paper was a firm Dreyfus supporter).

The female reporters had to obtain special permission to access places like the Assemblée Nationale and the Bourse de Paris from which all women were normally banned.

Photo: La Fronde enabled women to become professional journalists; Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France

She made feminism respectable

“Her work at La Fronde was double,” says Mary Louise Roberts. “On one level she wanted to make feminism respectable by making it the business of mainstream, middle-class and attractive women (rather than the somewhat eccentric types she considered feminists), and on another level, her interest in the paper was to make herself respectable too.

“She went to great lengths to make the offices correctly bourgeois and feminine. And she hosted parties which were highly valued by bourgeois and upper-class men.

“Feminism gave her respectability, while she made feminism respectable: that was the formula.”

La Fronde was a daily paper until 1905, when it became monthly. It ceased publication in 1905, and during its lifetime gave space to a wide range of female writers and reporters.

Read more: Simone Veil: a force for good, for women, for France, for all

She attacked Napoleon’s Code Civil that denied women legal status

In 1903, Marguerite Durand was a co-founder of the socialist, anti-clerical daily L’Action, alongside journalist Henry Bérenger and defrocked priest Victor Charbonnel.

In 1904, during the centenary of the publication of Napoleon’s Code Civil, she took the opportunity to attack it fiercely.

“There is not a woman who should not curse the Code. There is not a woman, rich or poor, a great lady or a worker, who in her poverty or her wealth, concerning herself, her children, her work or her leisure, has not suffered or will not suffer thanks to the Code.”

The Code Civil specified that married women should legally be considered as minors, that the husband was the head of the family and could direct everything as he saw fit, including where the family lived, how children were educated, and how money was spent.

Women had no legal status, they could not witness documents, nor could they sell or buy domestic items; they were legally obliged to obey their husbands.

Rape was not legally recognised within marriage. (Marital rape was only criminalised in 1996 in France, and the status of a man as ‘head of the family’ remained in force until 1970. Women finally won the vote in 1944).

Campaign for the right to vote and stand for office

In 1899, Marguerite Durand co-founded the animal cemetery in Asniéres (on the outskirts of Paris) along with a lawyer called Georges Harmois. It is still in use today, and can be visited by the general public.

Durand was indefatigable. In 1907, she organised a Congress on Women’s Work, and attempted to found an Office for Women’s Work within the Ministry of Employment.

In 1909, she was involved in setting up another publication called Les Nouvelles and she was constantly committed to the suffragette cause, forever arguing that women should not only have the right to vote but should also be able to run for office and be elected.

As part of the struggle, she presented herself as an electoral candidate, knowing that she would be refused.

Photo: Marguerite Durand in 1910; Credit: History and Art Collection / Alamy

Established a club for women journalists

In 1914, even though she felt that feminism and pacifism went hand in hand, she re-launched La Fronde for several editions, with an editorial line encouraging women to find ways to support the war.

She saw it as an opportunity for women to prove their capabilities in fields normally closed to them, including industry, agriculture, medicine, and transport.

In Britain, women won the vote in November 1918. French women, however, were still denied the vote, and both abortion and the advertising of contraception were banned in 1920.

In 1918, she became involved in the defence of the feminist, Hélène Brion, a teacher, a pacifist and a union member who wrote La Voie Féministe.

Brion had been arrested and jailed for ‘defeatist propaganda’ during the war, and was considered generally suspect because she often wore ‘men’s clothes’ (trousers). The case became something of a stage for feminist arguments about the rights of women.

In 1922, Durand organised an exhibition of famous 19th-century women to finance the creation of a club for female journalists, who were at that time excluded from male clubs.

When a feminist colleague called Séverine died, she bought her house in Pierrefonds and turned it into a summer home for women journalists.

She attempted to re-launch La Fronde between 1926 and 1928 with a mixed editorial team, using it as a voice for the Republican Socialist party that she supported. In 1927, she presented herself again for election.

Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand still exists today

In 1931, she gave her library and all its papers and documents to the city of Paris, creating the first Office de Documentation Féministe Français, which she managed as an unpaid volunteer until her death in 1936.

The BMD library (Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand) still exists today. It also houses a bust of Marguerite Durand sculpted by Léopold Bernstamm in 1897.

“I researched my book, Disruptive Acts: The New Woman in fin-de-siècle France at the Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand, and at the Fonds Marie-Louise Bouglé at the Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris,” notes Mary Louise Roberts.

Marguerite Durand is buried at the Batignolles cemetery in Paris.

Related articles

French minister defends appearance on Playboy magazine’s front cover

From Nazi war camp survivor to fêted anti-poverty campaigner in France

The female French spy who saved more than a thousand British soldiers