-

French MPs back plan to ban under-15s from social media

The bill also outlines rules for lycées – but may be rejected due to potential clash with EU regulations

-

Macron, Trump and Davos: how Franco-American relations hit a new low

Renowned political commentator Simon Heffer examines the French president's dilemma

-

Why are presidential photos mandatory in French mairies?

The framed image of the sitting president is a common feature in mairies alongside the flag and a bust of Marianne

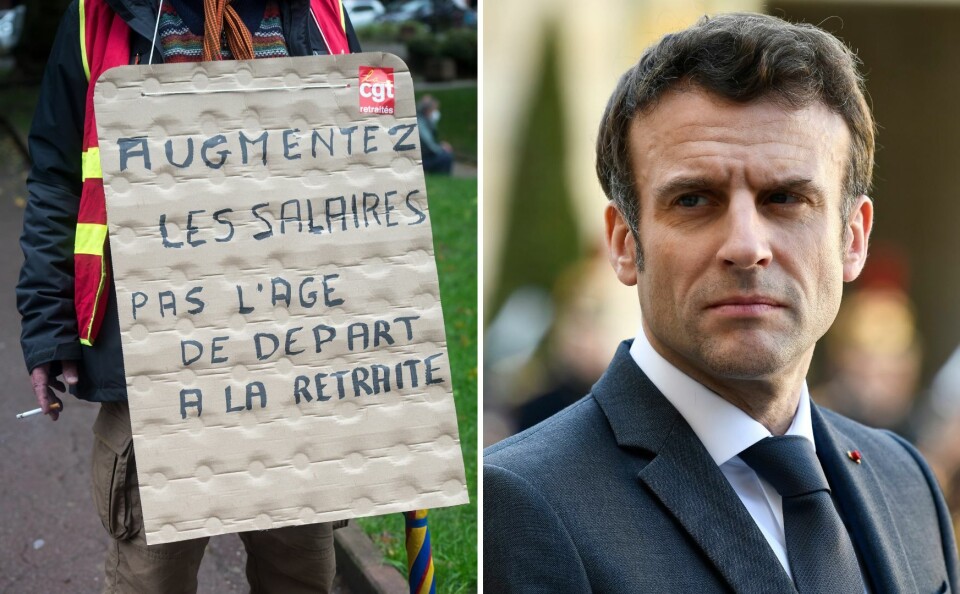

‘Pension age rise in France is unnecessary and will worsen inequality’

An economist tells us why he thinks President Macron really wants to increase the retirement age – it benefits business not pensioners

Unions say they will call for strike action starting in January if the French government pushes ahead with its plans to raise the retirement age to 65.

The reform was due to be presented in December, but this has been delayed until January 10. The bill is set to go before MPs in the spring before potentially being implemented from the summer.

Read more: Presentation of France's pension reform bill is deferred to January

Macron’s arguments are ‘pretext’

President Macron said during a recent television interview: “The financial burden is huge and will continue to grow in the years to come. The only lever we have is to work longer.”

He pledged to raise the retirement age to 65 as part of his recent re-election campaign.

However Michaël Zemmour, an economics lecturer at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, says there is only a “small deficit” forecast for the years to come and the system is not in danger.

He believes this is being used as a “pretext” for pushing through a reform that the government wants for other reasons: namely, to reduce public spending to compensate for cutting taxes on businesses, and to increase productivity by making people work longer.

“As these reasons would not go down well, the government is citing a third reason – the threat to the pensions system – but this is not a serious reason.”

Read more: Labour shortage: France plans to tighten unemployment benefit rules

Report finds spending on pensions will remain stable

In a report published in September, the Conseil d’orientation des retraites advisory body concluded spending on pensions as a percentage of GDP would remain stable in the next five years, from 13.8% in 2021 to 13.9% in 2027.

It should then increase from 2028 to 2032, to between 14.2% and 14.7%.

However, this is due to remain stable, or decrease, between 2032 and 2070.

It is predicted the ageing population will be counterbalanced by the effects of previous reforms raising the retirement age, and by the smaller improvement to pensioners’ living conditions compared to working-age people.

“We are still yet to see the full effects of the previous reforms in France,”he said.

A 2010 reform raised the minimum legal retirement age from 60 to 62, and raised the age when anybody can claim a full pension, if they have not worked the required amount of time, from 65 to 67.

In 2014, the minimum number of trimestres for which you need to have been paying into the system to claim a full pension was gradually raised from 166 (41.5 years), for people born between 1955 and 1957, to 172 (43 years) for those born from 1973.

It had previously been 37.5 years until an earlier reform in 1993.

The average retirement age will reach almost 63 by 2030, and 64 in 2040, without further reform, according to a 2018 report from the government think tank France Stratégie.

Read more: Retirement at 65 (not 62) and €1,100 monthly pension: Macron’s plans

Health toll and businesses not employing older people

“People who retired 10 years ago will have a longer retirement than those who stop working today. Since the 2010s, the increase in life expectancy is smaller than the changes to the retirement age,” Dr Zemmour said.

Raising the retirement age could also entrench inequality between those who are in and out of work, he added.

“Those who work until they are 62 will work a couple of years longer, but the 30% to 40% of people who are no longer in work by the time they retire will experience a longer period of economic insecurity.”

In 2018, for every 10 French people aged 60, four were in work, three were retired, and three were either unemployed or economically inactive, according to France Stratégie.

“Retirement protects from insecurity,” Dr Zemmour said. “Most people who retire lose spending power but for the poorest 40%, their income increases, because they acquire a status.”

Among the reasons for these high inactivity rates are the health toll taken by difficult working conditions and businesses not hiring older workers.

According to European Commission data, the average French person leaves the labour market aged 62.3, compared to 63.8 across the EU.

Read more: France’s retirement age debate: What is the healthy life years metric?

60% of mayors are over 60

Dr Zemmour says delaying retirement to a time when people are much less capable of remaining active would transform the way it is experienced.

“In France, political life and volunteer work depend on retired people, as does childcare. Retirement is no longer a time to do nothing.”

He said this trend dates back to François Mitterrand’s decision to lower the retirement age to 60, and is linked to high rates of employment among women, and low rates of part-time work, meaning it often falls to pensioners to run associations, sports clubs and other groups.

According to the Institut Montaigne think tank, 60% of mayors and 40% of departmental councillors in France are over 60.

Reform should address gender inequalities

As well as advantages in terms of health and income, there are macro-economic benefits to maintaining the retirement age at 62, the researcher said.

“Pensioners are better protected from the fluctuations of the economy, and from crises, so they maintain a certain level of consumption, which can soften the impact of a crisis.”

Rather than changing the retirement age, he believes any reform should address gender inequalities due to the fact that people who have not worked their entire adult lives, often women, can end up with measly pensions.

In a press release published in December, the CFDT, CGT, FO, CFE-CGC, CFTC, Unsa, Solidaires, and FSU unions, as well as student organisations, warned of “a major social conflict”.

They announced their intention to organise a first round of strikes and protests “in January if the government digs its heels in over its project”.

Related articles

Why fewer bills are likely to be forced past French MPs next year

Inflation, retirement, immigration: Key points from Macron interview

Can we claim French pension from jobs in France now we live in the UK?