-

Bread, bacon and beans: British food habits on trial in France

Columnist Samantha David carefully navigates a discussion with a taxi driver on a delicate subject: the French breakfast

-

France's new foreign income rules are making our lives complicated

Readers outline their struggles in getting French nationality

-

France's DPE energy rules may leave beautiful older homes worthless

Connexion reader's 500-year old home was rated F

Rebuilding church’s long lost tower is ‘historic lie’

The editor of the art and heritage magazine La Tribune de l’Art Didier Rykner explains why he opposes a project to restore the missing tower of the Basilica Saint-Denis, north of Paris

The Basilica, which houses the tombs of kings of France, has been missing one of its towers after it was dismantled following storm damage in 1846. Starting next year workers will attempt to rebuild it using ‘authentic’ medieval techniques and, from early 2018, a viewing structure, including a restaurant, will be built so the public can watch. The work is to be funded by money from visitors and donors. However Mr Rykner told Connexion he disagrees with the plan.

“I’m opposed to the reconstruction of monuments, or parts of them, that haven’t existed for a long time. This tower was demolished in the middle of the 19th century.

“It’s totally absurd, firstly because what they’re building is a fake and, secondly, because the money would be better spent elsewhere. When you see the amount of churches in Paris that are falling to bits spending all this money [an estimated €12-13million] to rebuild part of this church seems an aberration.

“What’s more they want the work to go on for as long as possible to bring money in – the longer it takes, the better, they say. So for 10-15 years we’ll see the façade under work, when it is completely unnecessary.”

He said he is not opposed to all reconstruction, for example, the rebuilding of something that has just been destroyed, perhaps in a war, but he is against rebuilding long-gone buildings.

Asked why he sees it as a ‘fake’ if it will be rebuilt in the same way, perhaps even using original stones [the mairie claimed the old stones had been retained in storage], he said: “That was just a story from the promoters – it’s false and they’ve even admitted it; there’s maybe a tenth of the stones that still exist and they’re probably not even usable because of their poor condition.

“And if you make a fake painting, you try to use the same pigments and the same composition, but it’s still a fake. Plus it’s against the Vienna Charter, signed by France, which says you shouldn’t reconstruct lost structures to make people believe they’re real.

“It would have been preferable for the second tower not to fall, but it did – that’s history. Adding on a fake to an original building isn’t making it more beautiful. It’s an historic lie.”

As for the promise that the project will not cost the state anything, he said: “Firstly I don’t believe it – the council has already committed to giving money if necessary, which proves they may not believe it either. Plus the donors will have tax relief so part is paid by the taxpayer. I’m not against that in principle – we should be giving more money to culture but not for this.”

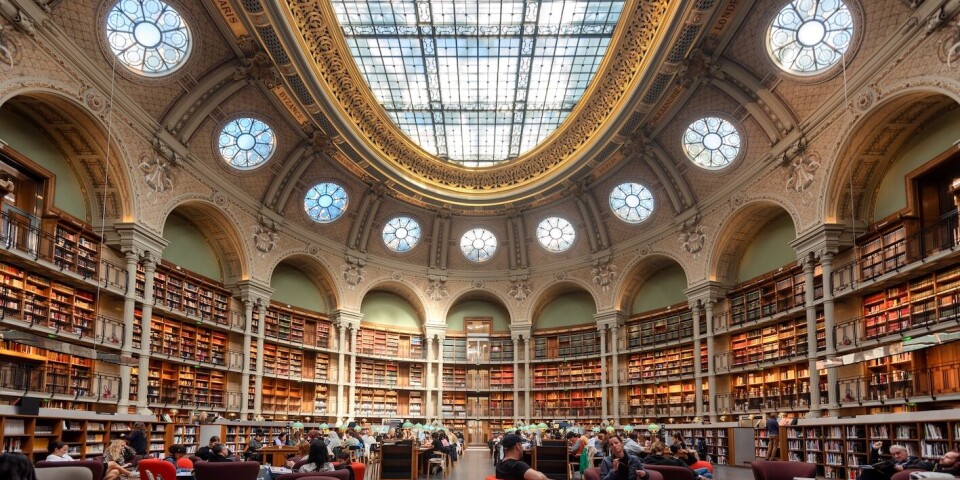

Many churches are in dire need of restoration (not rebuilding), he said. “They are in a disastrous state. Paris is a city on the road to ruin, in terms of its heritage. It’s monstrous.”

Groups exist that seek to rebuild certain lost buildings that have completely disappeared, such as the Château de Saint-Cloud, between Paris and Versailles, or the 226m-long Palais des Tuileries which used to abut onto the Louvre.

However Mr Rykner said that is ‘even worse’. “One could argue that at Saint-Denis they just want to restore the harmony of the façade, but at the Tuileries there’s nothing left. We’ve extended the gardens instead and the inside faces of the parts of the Louvre which joined it have been renovated. It would be a case of vandalism, of destruction, to try to rebuild it again.”

Mr Rykner said people who “don’t know anything about heritage think it’s a great thing”, however in reality “heritage is very much under threat because we don’t spend enough on it” and while France already has “wonderful laws” on protecting heritage, “they are not respected” and “there’s a tradition of vandalism”.

There are certain well-known examples of rebuilding in France, but they are not comparable, he said. For example the Hôtel de Ville de Paris, which was rebuilt in the 1870s after a fire. “It burned during the Paris Commune period, 150 years ago, so for a start we’re not in the same context at all and protection of heritage has progressed. But it burned, it wasn’t completely knocked down, so it was normal to rebuild. Plus they didn’t try to make it exactly the same. They used a ‘neo-Renaissance’ style and inside they didn’t repaint the ceilings in the same way”.

As for the Corderie Royale in Rochefort, devastated by bombing during the Second World War and largely rebuilt in the 1980s, he said such projects may be suitable for ‘symbolic’ reasons, much as the Syrians might rebuild parts of Palmyra, so as ‘to show that barbarism will not prevail’.