-

How many Americans live in Paris - and where else are they choosing in France?

Over a quarter of all US nationals in France live in the capital city

-

Price rises for Netflix in France

The Standard (with ads) and Premium packages are increasing by €24 a year

-

Leclerc supermarkets to sell car fuel at cost price for Easter

The initiative will apply to diesel, petrol, and LPG

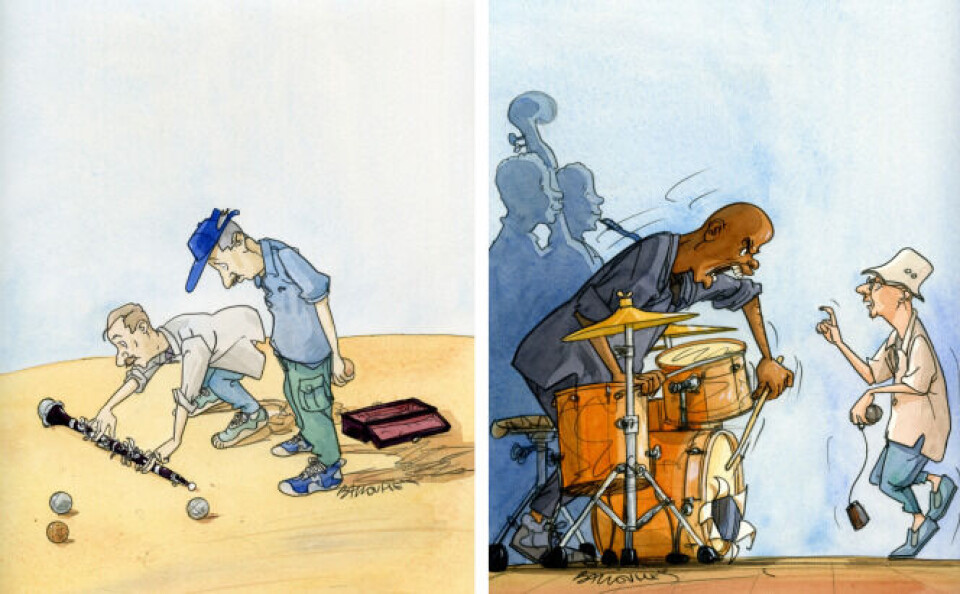

Sempé was a master illustrator but also a sociologist, say cartoonists

‘He had all of what is needed; composition, graphism, colour, expressions and a great sense of what a good caption is’

Two French cartoonists have described to The Connexion the impact, inspiration and unique style Jean-Jacques Sempé has left on the cartoonist industry as well as French society, following the illustrator’s death on August 11.

Both said they drew inspiration from Sempé’s early work and considered him to be a masterful cartoonist whose insightful drawings were a sociological deconstruction of French people.

Sempé was one of France’s best-known cartoonists, known to almost everyone in the country as the co-founder, with René Goscinny, of the Petit Nicolas children’s book series.

He also achieved international recognition as the illustrator of 106 New Yorker covers.

His drawings – which portrayed a both poetic and amusing view of the world – have inspired countless other cartoonists and featured in expositions and motion pictures, among other cultural forms.

Read more: An image tribute to France’s Petit Nicolas illustrator Sempé

“We lose our innocence, our childhood, our youth with Sempé’s death,” said Pierre Ballouhey, cartoonist who was featured in The Guardian, The New Yorker and is a regular contributor to other French publications.

Mr Ballouhey was among the throngs of French people and cartoonists to pay tribute to Sempé with a publication of one of his drawings on his personal Twitter page.

Read more: French cartoonist Plantu retires after 49 years at Le Monde

Mr Ballouhey said that Sempé was admired for his very characteristic style, alignments of Haussmanian’s buildings, avenues and crowds with great perspective and a thin inking technique that helped in maintaining movement from characters.

“There is a ‘style Sempé’, characters ‘à la Sempé’, crowds ‘à la Sempé’,” said Mr Ballouhey, adding that he unconsciously developed in his own drawings characters that resembled to those of Mr Sempé.

Mr Ballouhey said some of his characters were ‘à la Sempé’ as they represented the common French person without any pretension.

Aside from Le Petit Nicolas - Sempé’s most famous character known to almost every French person is Monsieur Lambert, a character depicting the average French man who took strolls in Parisian parks and avenues and stumbled through the tumults of daily life.

Sempé set most of his drawings in a nostalgic, romantic and poetic version of Paris of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s – a Paris where the intelligentsia and intellectual life thrived.

His drawings were inspired by his parents’ conflicts and arguments that he would eavesdrop on and a childhood where he was mocked at school for having a stammer.

“He was one of the very last masters of humoristic drawings,” said Michel Cambon, a cartoonist who often appears in regional newspapers in the Grenoble area.

He added that such is Sempé’s greatness, he deserves to rest in the metaphorical “Pantheon of drawers” along with other renowned cartoonists Chaval and JB Handelsman.

Mr Cambon compared his relationship with Sempé to that of a disciple toward a master, having never met him but only studied his drawings since his childhood.

“He had all of what is needed in our industry. Composition, graphism, colour, expressions and a great sense of what a good caption is,” said Mr Cambon.

Mr Cambon said he always opens one of Sempé’s books when he needs to draw a bicycle.

Both Mr Cambon and Mr Ballouhey said Sempé was in a way also a sociologist, able to see sides of society that most others could not and capture that in his work. They praised his depiction of daily life, be it illustrating couples in love, satirising politicians or simply showing the monotonous grind.

Sempé’s work came at a time when sociologist Pierre Bourdeau and writers Georges Perec, with novel ‘Les Choses’ or Roland Barthes with ‘Mythologies’ took on other cultural forms to analyse France in the 1960s.

Sempé, however, always refused to be characterised as such, saying: “If I am a sociologist, what were writers Balzac and Proust?”

Related articles

Plantu: The power of press cartoons

Cartooning for Peace: Let's build bridges through cartoons