-

Photos: 94 chateaux open their doors to visitors in Dordogne

The fifth Chateaux en Fête festival offers a chance to look around many impressive properties that are usually private

-

Ballet lessons bring health benefits to over-55s in France

Online classes with the Silver Swans are transforming lives of older adults

-

How to define your style and make a French property a home

'There is always a balance between the inhabitant and the provenance of the building'

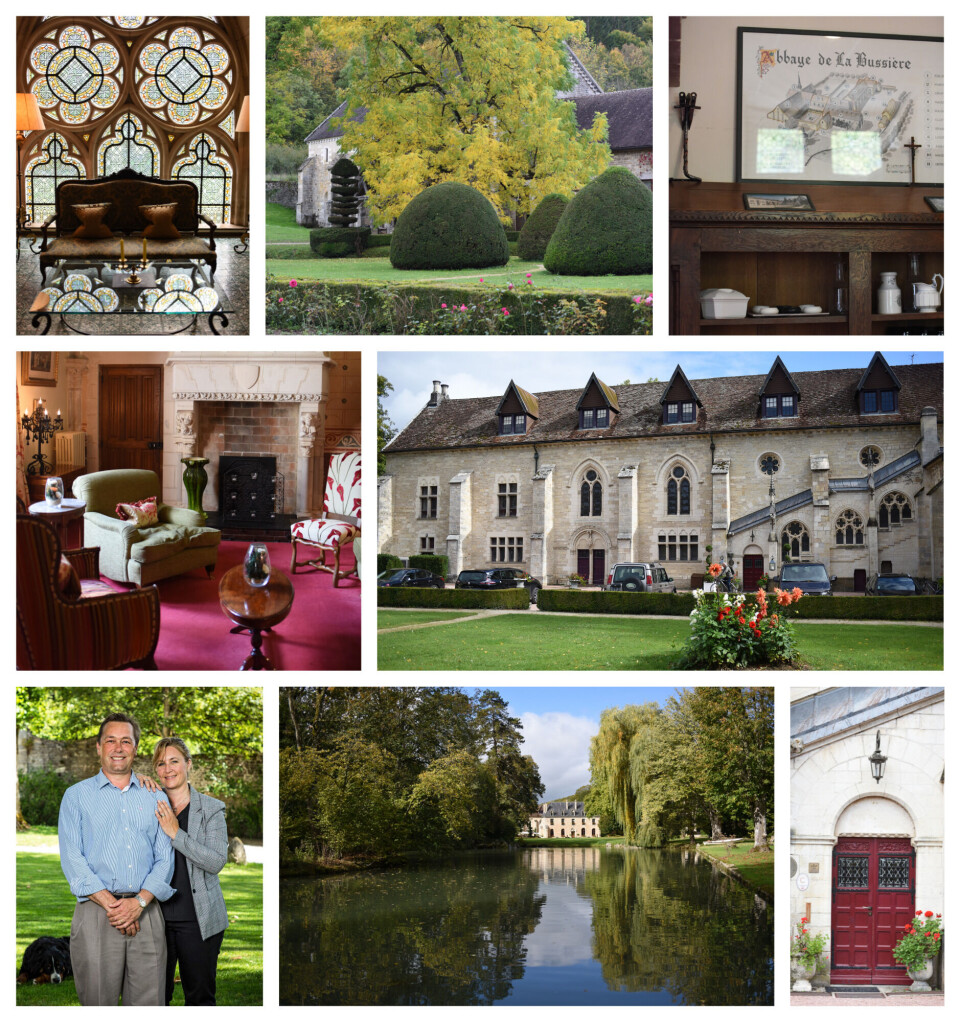

We bought a hotel in France: From ‘go home’ graffiti to Michelin star

A British couple saved an abbey from financial ruin and turned it into a luxury hotel. They say it was road full of pitfalls but worth it

Clive Cummings was under no illusion that transforming a run-down Cistercian abbey from a €56-a-night spartan retreat into a luxury hotel would be easy, but it became a nightmare as he faced deep local hostility and ‘Go home rosbifs’ graffiti.

Today, looking back to the dark days after 2005 when he and wife Tanith bought the abbey in the heart of Burgundy’s Côte-d’Or, Clive said he is “loving his hotel nightmare” now it has turned into a dream.

Since then, they have battled with bureaucracy, cut a way through the problems of a €1.5million overspend, completely remodelled the buildings... and all while trying to learn French and raise a family of four.

Then, as they tasted success, they faced the paralysis of the pandemic.

Deep in the countryside west of Dijon, the gargoyled, spired and stained-glass Abbaye de la Bussière is now a luxury Relais & Chateaux with Michelin-star restaurant and a place on the gastronomic Tour de France.

It sits by a lake in a vast park in tiny La Bussière-sur-Ouche commune and Clive said: “I’ve walked around that lake many a time thinking ‘Oh my God, how do I get myself out of this?’.

Challenges were nothing new to Clive and family. The son of British high-end hoteliers, he helped his parents convert Amberley Castle in West Sussex into a luxury hotel restaurant in the 1980s, while training to be a chef at Westminster College, London.

The abbey was different. Founded by an English monk in 1131, it is a historic monument and was bought on impulse.

“A friend of a friend phoned one night and said there’s an abbey in Burgundy owned by the Church and the Archbishop of Dijon can’t afford to run it any more, and it would be such a shame as it’s a beautiful spot.

“We jumped on the Eurostar and came down to see it – myself, my mum and my dad – and we loved it. “I remember driving down through the Vallée de l’Ouche and thinking ‘Oh my God, this is too good’.

‘It’s such a privilege to have been the family that saved it from being closed’

“We signed the compromis de vente [provisional sales deal] the same day.” They faced many pitfalls, not least bureaucratic and financial, but also months of battles with locals and the authorities.

Clive said wryly: “The pressure on finances has been huge. Everyone expected from day one we were going to be an upmarket Michelin-star hotel – Relais & Châteaux-style.

“We had to come up with the goods. That’s not cheap. You’ve got to employ the right people. You’ve got to have the right quality of everything, down to bedsheets, silver and tableware.”

All that, despite the cultural differences: “It’s not only a different language and way of life, but it’s a different ethos on business and tax as well, and trying to learn that is hard.”

The abbey had been run as a spartan spiritual retreat – and it was not easy convincing the Church powers to convert it for hedonistic luxury.

“It had 60 single rooms, shared toilets and showers. There were plastic chairs, paper tablecloths, all the walls were just painted white. It cost €56 a night for dinner, bed and breakfast, including half a bottle of wine.”

His first encounter with the French work ethic was a rude one. “Part of the deal was to honour existing business for six months.

The staff would leave at nine at night because of their 35-hour week. “If you hadn’t finished your meal by then, they brought everything else out and put it in front of you, including coffee in a flask. Then they would lock the kitchens and leave you on your own.

“So I came from a prestigious Relais & Châteaux hotel in England to a sanctuary in France where everyone was walking around in flipflops and shorts, and life was cool and easy.

“People were doing their yoga and exercises out in the garden at 6:00 and it was a bit of a shock.” Clearly, they had a job on their hands reorienting the clientele, but first they had to do the architectural makeover, which was a massive, complicated task to respect heritage laws while creating nine rooms in former monks’ chambers.

‘There was an immediate outcry and backlash and legal cases to annul the sale’

All this while facing huge hostility from locals, with ‘Go home rosbifs’ scrawled on the abbey walls. “When it was announced that the archbishop had sold the abbey, there was an immediate outcry and backlash: a petition of three-and-a-half thousand signatures and three legal cases trying to annul the sale, saying the Church could not sell assets.

“They thought, to quote the papers, we were going to ‘create a paradise for playboys and stuff the locals’.” Meanwhile, Clive and Tanith had four children under the age of 10 to get into local schools, “despite none of us speaking a word of French”.

Language was also a barrier with French banks, which tend to be more conservative and cautious.

“And we had overspent by €1.5million...” The revamp cost a small fortune but Clive also had a culinary problem: “In France, they don’t eat a full cooked breakfast.

You sit there with a nice yogurt, a bit of fresh fruit, a little bit of charcuterie and pastries. Whereas the English want a great big greasy fry-up – even when they are in France.”

British and American tourists do not necessarily come to France in search of gastronomy, particularly not the Brits.

He said: “Sometimes I bang my head against a brick wall when I get people saying ‘Why haven’t you got this, why haven’t you got that?’.

And I say ‘Well, this is a French hotel. Burgundy is a very gastronomic region and we want to highlight that.’” Yet, insisting on French authenticity has paid off.

The abbey’s Restaurant le 1131 has gathered culinary accolades, with a Michelin star thanks to local chef Guillaume Royer, who won the 2015 Meilleur Ouvrier de France title.

Two years later, Gault et Millau guide dubbed him Grands de Demain (great chef of tomorrow).

His menu showcases the best of the Bourguignon terroir, local and seasonal, of which he, like the abbey owners, is a staunch defender.

The abbey’s culinary excellence was crowned with the label 100% Côte-d’Or Savoir-Faire – a marketing brand for quality Côte-d’Or producers.

It’s quite uncanny in this very traditional part of France to find such a French/English hybrid on the luxury hotel scene.

Clive laughingly calls it his “DIY chateau” and said: “I learn something new every week here. It’s just such a privilege to be part of the history – and to have been the family that saved it from being closed.

“When you close a building like this, it doesn’t take long before the roof falls in.” His recommendation to anyone thinking of going down his path is to stay closely in tune with local French lore and the natural and the natural and historical milieu you buy into.

Related articles

Top tourism award for restored abbey

Fondation du patrimoine saves 35,000 buildings in France in 25 years