-

Explosion at chemical plant near Lyon: where are other ‘at risk’ sites in France?

An estimated 2.5 million people live within a kilometre of a French Seveso site

-

Farmer blockades to continue on motorways over Christmas in south-west France

Protests are being maintained on the A64, A83 and A63 and on departmental roads

-

Interview: UK-France relations will only get stronger this year says new British Ambassador

The Connexion speaks to Sir Thomas Drew, who took up the role on September 1

Will today’s ‘high-stake’ TV debate really influence French election?

We ask political experts and a linguist for their views on the traditional face-off between second round candidates

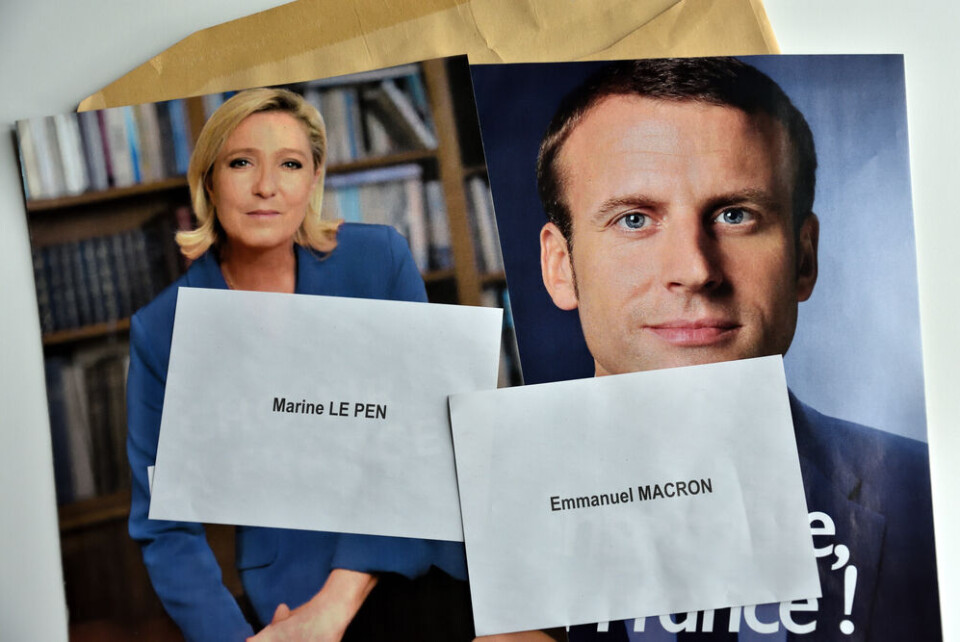

President Emmanuel Macron and Rassemblement national candidate Marine Le Pen will face each other tonight at 21:00 during the ‘débat de l’entre-deux-tours’, the televised political debate in which the two candidates have traditionally appeared since 1974.

The 2022 edition is the rematch of the last presidential election debate in 2017 and will be broadcast by French channels TF1, France 2, FranceInfo and LCI and animated by TF1 anchor Gilles Boulleau and France 2 and France Inter journalist Léa Salamé.

“We are facilitators. We will do everything to make sure that the debate takes place in perfect equality, equity, transparency and dignity,” Mr Bouleau has said. “We are there to create a rhythm, to move from one theme to another, to keep an eye on the equality of the stopwatches,” Ms Salamé added.

In 2017, 16.4 million people tuned in to watch the debate, in which it was generally agreed that Mr Macron came out on top.

Read more: Presidential TV debate and election: the week ahead in France

‘The stakes are high’

Political experts told The Connexion how the current French political context sets the rematch apart from that of 2017, but casted doubts on the magnitude in voting shift it could have ahead of Sunday’s poll.

They also told of the evolution of the debate between 1974 to 2017, often characterised as a symbolic, traditional and very regimented ritual of the French Fifth Republic.

“The stakes are high,” said Marc Crapez, political expert at the Sophiapol laboratory of the University of Paris-Descartes, adding that the debate comes in a political atmosphere characterised by people “losing faith in the ability of democracy to renew itself.”

Mr Crapez said Ms Le Pen appeared stronger than ever in polls because of repeated failures from former presidents who pledged but eventually did not introduce more proportional representation and stronger use of referendums, two democratic tools which give the electorate greater political expression.

He said the debate will be the opposition between two visions of the future of French society with the pro-globalisation and pro-European camp incarnated by Mr Macron and the nationalistic camp of Ms Le Pen.

Read more:What is Le Pen’s ‘French nationals first’ policy and is it legal?

A rematch of the 2017 debate

“Macron is the candidate that has the most to lose,” said Pierre Sadran, political science teacher at Sciences Po Bordeaux, referring to close polls between the two candidates.

Mr Macron is regularly credited with 53 to 55% of voting intentions across various polls but a Fiducial-Ifop poll for French channel TF1closed the gap to a 51% / 49% battle between the two candidates on April 10 following the results of the first round.

Mr Sadran said the debate could see a small switch in voting intention large enough to tip the scale in favour of Ms Le Pen in the event of Mr Macron pronouncing a sentence that would be perceived as “arrogant” by the working-class, a regular complaint from French people.

Read more:‘Piss off the unvaccinated’: Not first time Macron’s words cause stir

He said Macron’s situation is more difficult than it was in 2017 since he is no longer perceived as a challenger eager to revolutionise French politics but as a president with a five-year-term to defend.

Mr Sadran said this was reinforced by the fact that several of Mr Macron’s quotes had caused shock and outrage in France and by the trend of making decisions based more on emotion than previously.

“Mr Macron no longer appears as the republican alternative to block the far-right from reaching office,” said Pascal Marchand, political science teacher at the University of Toulouse.

Mr Marchand’s comment links to the fact that some of Mr Macron’s policies have veered closer to the right spectrum (sometimes far-right) in an effort to appeal to conservative voters.

Examples include his plan to up the retirement age to 65, the reduction of hospital beds during the pandemic and an overall policy in favour of more privatisation.

“Mr Macron crystallised hatred among Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters,” said Mr Sadran.

Mr Mélenchon told his 7.7 million voters to “not to give a single vote” to Ms Le Pen (Rassemblement national). However, he did not specifically tell his voters to cast a ballot for Mr Macron.

Read more: 'Macron or Le Pen: It's like choosing between the plague or cholera'

Read more: French election: The chase is on for Mélenchon’s 7.7 million voters

The debate will also be important for Ms Le Pen, who will look to convince French people that she is worthy of the presidency after she admitted “failures” in the 2017 debate, where she “paid a high price” for her aggressiveness and a lack of preparation.

A ritual and a tradition

Political experts told The Connexion the debate is a symbolic moment in which two candidates are summoned before French people to lay out the proposals developed throughout their campaign. People also watch it eagerly on the lookout for memorable quotes and punchlines.

“It is a ritual that is needed,” said Mr Marchand.

The ‘débat de l’entre-deux-tours’ was originally not intended to become a tradition when Charles De Gaulle enacted the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, although he gave a one-on-one TV-interview with journalist Michel Droit during the first presidential election in 1965.

The first debate happened in 1974 between Valery Giscard d’Estaing and François Mitterrand and was meant to display a clear distinction between candidates. It has almost always happened ever since but is not deemed mandatory by any legislative law.

The only sitting president to have refused to debate was Jacques Chirac, who would not appear against Jean-Marie Le Pen (leader of the Front National and Ms Le Pen’s father) in 2002, arguing he would never debate against far-right candidates.

Some of the debate left political commentators and French people with lasting and memorables quotes such as the “monopole du coeur” from Valéry Giscard-d’Estaing in 1974, the “l’homme du passé et l’homme du passif” in 1981 and the “vous avez tout à fait raison, Monsieur le premier ministre” in 1988 by François Mitterrand or the “Moi, président” in 2012 by François Hollande.

The ‘monopole du coeur’ quote is believed to have convinced 300,000 people to vote for Mr Giscard-d’Estaing in what remains the closest margin between two French presidential candidates, although the figure is not backed by any scientific study.

Political experts told The Connexion the quotes and the debate itself play a minor impact in voters’ decision since most have already decided what to vote before the debate starts.

“A political turnaround such as in 1974 or 1981 looks almost impossible,” said Mr Crapez.

Mr Marchand said he does not believe the debate will have a massive impact on Sunday’s polls although he believed candidates will use tactics to provoke political faux-pas.

2017 was the pinnacle of aggression

But Mr Marchand said the behaviour of presidential candidates during the debate had gone through four stages of evolution since the 1960s and was at another “turning point” now.

He said presidential candidates in the 60s and 70s appeared closer to their programmes and political leaning. The 80s were characterised by politicians who wanted to appear as technicians who would be best suited to run the many layers of the political machinery.

The third period, he said, started around the 00s and finished around the latest presidential debate in 2017 and was characterised by seductive behaviours toward voters with the extensive use of campaign aides and political communication rhetoric.

But it reached a pinnacle in terms of aggression in 2017 after interruptions and slang terms gradually crept into the exchanges, said Catherine Kerbrat-Orecchioni, a linguist who has written about every presidential debate in two books.

“Ms Le Pen crossed the red line in 2017,” said Ms Kerbrat-Orecchioni, adding the debate had shown a dissymmetry between Mr Macron, who is calmer and clearer in speech, and Ms Le Pen, who uses colloquial language and ad hominem insults, doing away with a tradition of civility in speech and vocabulary.

“Ms Le Pen will probably mix water with wine this time,” said Ms Kerbrat-Orecchioni.

Mr Marchand said both candidates now use market and sales research techniques to appeal to voters, adding the debate was no longer considered as the opposition between the right and left spectrum but one more round of a political campaign in which candidates need to gain market shares.

He weighed his theory on the dichotomy between what appeared written on both candidates’ campaign programmes and what the candidates have spoken about in campaign trails, referring to bargaining techniques on some of their key-campaign points.

How will tonight’s debate look?

Both candidates have lowered some of the campaign programmes during the ‘entre-deux-tours’ period in an effort to appeal to leftist voters with Mr Macron saying he would open retirement to 64 in some cases and Ms Le Pen saying the headscarf ban is no longer a priority.

Read more: Marine Le Pen says French headscarf ban ‘no longer main priority’

The debate itself remains a technical and very regimented exercise.

Both sides of the debate have appointed an advisor who will make sure that they stick to the image they want to portray by talking into their earpieces if necessary. Ms Le Pen has chosen forer LCI journalist and Rassemblement national member Philippe Ballard, and Mr Macron has opted for director Jérôme Revon.

Both candidates have also asked the TF1 group for specific lighting and camera angles and the journalists are obliged to provide equal-speaking time. Spending power was chosen to be the first subject of discussion with Ms Le Pen opening, both decisions taken by the channel by a random draw.

In all, there will be eight topics debated, ranging from international affairs to pensions to education to immigration.

Ms Le Pen is expected to be much better prepared than she was five years ago, with one of Macron’s strategists saying: “I expect a solid performance on her part.”

It will be Mr Macron’s job to deconstruct any emerging image of a Ms Le Pen who champions public spending power, with a “project against project” approach.

Related articles

What is Marine Le Pen’s position on the death penalty?

Macron - Le Pen: What do they each pledge to change if elected?