-

Top French court clarifies rules on foreign language wills

Certain conditions must be met for a language to be accepted if it is unknown to the testator

-

Local election rule changes in France and why you may have a new mayor in 2026

Communes with fewer than 1,000 residents are particularly set to see changes from next year

-

Marine Le Pen appeal decision should be given in summer 2026, says court

It comes as the RN leader continues to maintain her ‘innocence’ and right-wing politicians have called her conviction ‘an attack on democracy’

Explainer: How criminal courts and jury service work in France

We look at the active role of judges, how cases are tried and why the system is so slow

Whether you admire or loathe him, Napoleon was responsible for swathes of French institutions, from lycées to departments – and the legal system is a prime example.

Before the Revolution, the various systems around the land reflected the slow unification of France.

Church law was mixed with local customs and a system of Roman law based on statutory law in the south and Germanic law based on royal decrees in the north. Local aristocrats and craft guilds also played a role.

When the Revolution came, many leading revolutionaries, including Danton and Robespierre, were lawyers, so it is not surprising that they saw creating a more unified system as important – but they failed.

It took Napoleon to effect lasting change.

His Code civil des français was completed in 1804 and covered civil law in great detail.

He also produced codes for criminal law, established unified working rules for courts, and created administrative law.

Codes for commerce and for specialist areas such as insurance have been produced since, but are all based on the principles of the Code civil.

Read more: Difference between contravention, délit and crime in France

The investigating judge plays a large role in French justice

Anyone who has read Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels will know one of the big differences between the Anglo-Saxon and French legal systems is the role of the juge d’instruction (investigating judge), to whom Commissaire Maigret must constantly report.

Such a judge is involved in all very serious criminal cases – where someone is accused of un crime (such as murder or rape) – but is optional in medium-severity crimes (délits) or low-level contraventions.

They are appointed by the local procureur (public prosecutor) to be in charge of investigations and can order the police or gendarmes to follow – or stop – a certain line of inquiry.

A key moment in any big case comes when the accused is questioned by the investigating judge. This is used by the public prosecutor to decide if the case will go to trial.

Statements made to the police are referred to by the investigating judge during this process, and can be used in court, but it is the judge’s report that carries the most weight.

Judges can also order meetings, in their offices, between the accused and witnesses, as well as reconstructions of crimes, to try to understand what happened.

Read more: Free help for crime victims in France including foreign nationals

Different government departments oversee police and judges

This system has inbuilt tensions – the police are under the interior minister, while judges and prisons fall under the justice minister.

In autumn 2023, a number of police officers got into trouble for saying that law and order problems in France lie not with the police but with the judges.

Similarly, the fact that judges belong to unions, including some extreme left-wing ones, has prompted questions about their impartiality.

During Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidency, for example, one union building was found to have a noticeboard labelled mur des cons (wall of idiots) on which photos of various public figures – politicians, intellectuals or journalists, mostly from the Right, senior judges and police unionists – were displayed, as well as photos of various victims’ parents.

Court system very different to UK

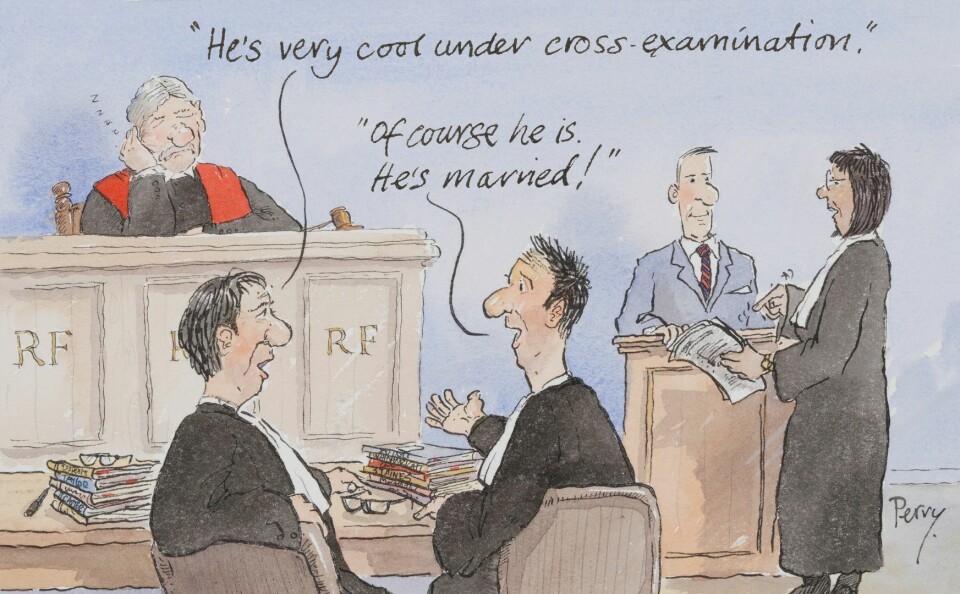

French court procedures differ significantly from, for example, English and Welsh ones.

Broadly speaking, the latter are adversarial, with the prosecution and defence each presenting their version of what happened, and the judge and jury, if there is one, sitting above the fray before deciding who to believe.

By contrast, the French system is inquisitorial, based on the tradition of law inherited from the Roman Catholic church.

The idea is that the court, including defence, prosecution and judges, is there to find out the truth by inquiry.

The best way of doing so is to have the accused confess their crime and, if they do not, to question everything about the case to establish the facts of what happened.

Read more: Briton appeals conviction for killing his wife in south-west France

Trial judge chairs jury deliberations

During proceedings, trial judges participate actively.

They read out the investigating judge’s report and when witnesses and defendants are called to the bar, they have to answer questions from the judge or judges as well as from their own lawyer and the prosecution.

If there is a jury, its members retire with the judge to decide their verdict. The judge assumes the role of chairperson and leads the deliberations.

Where there is no confession from the accused, witnesses and experts are cross-examined so the court can determine whether or not to believe them.

Why is the French system so slow?

One problem with the system is how slow it is.

A murder trial where the culprit is arrested with a smoking gun standing over the victim and makes a full confession to the police and investigating judge will still take four years to conclude. Complex investigations take longer.

Part of the problem is that many lower courts were shut by Rachida Dati when she was justice minister in 2007-2009 as a cost-saving measure.

In addition, court officers and judges are fonctionnaires and work only a 35-hour week with generous holidays.

Different courts hear different levels of crime

The most serious cases are heard in a cour d’assises, the top-level criminal court, of which there is one per department that sits four times a year.

It is the only one using juries and, as of 2023, only hears appeals trials or cases with potential sentences of at least 20 years.

Below the cour d’assises, there is the cour criminelle, in which a panel of five judges hears cases relating to crimes with a maximum punishment of 15-20 years.

The tribunal correctionnel rules on délits and the tribunal de police deals withcontraventions, in most cases without any actual hearing being held.

Jury service in France

Only French citizens aged 23 and above can be jurors (exceptions include police officers and MPs) and they are chosen at random from electoral lists.

They are notified by letter, including the date and time of the start of the session they are to attend and rough expected length – about two weeks, during which a juror might hear around 10 cases.

Jury service is obligatory unless you show a serious reason, mainly health-related, why you cannot do it.

Employees are not paid during jury service but financial compensation is given.

Related articles

Explainer: Speed cameras, fines and driving licence points in France

13 things French ‘commissaires de justice’ do apart from collect debts

Why France’s justice minister is himself on trial