-

What you should do to your garden in France in spring

Weeding, pruning, sowing, preparing the lawn…here is how to welcome sunnier days

-

Rules change for dog walking in France from April

Here is how to ensure you and your dog remain within the rules and avoid fines

-

Mimosa is pretty…but ‘posing threat to biodiversity’ in south of France

The flowers are prized in the region, but not everyone is thrilled to see their spread

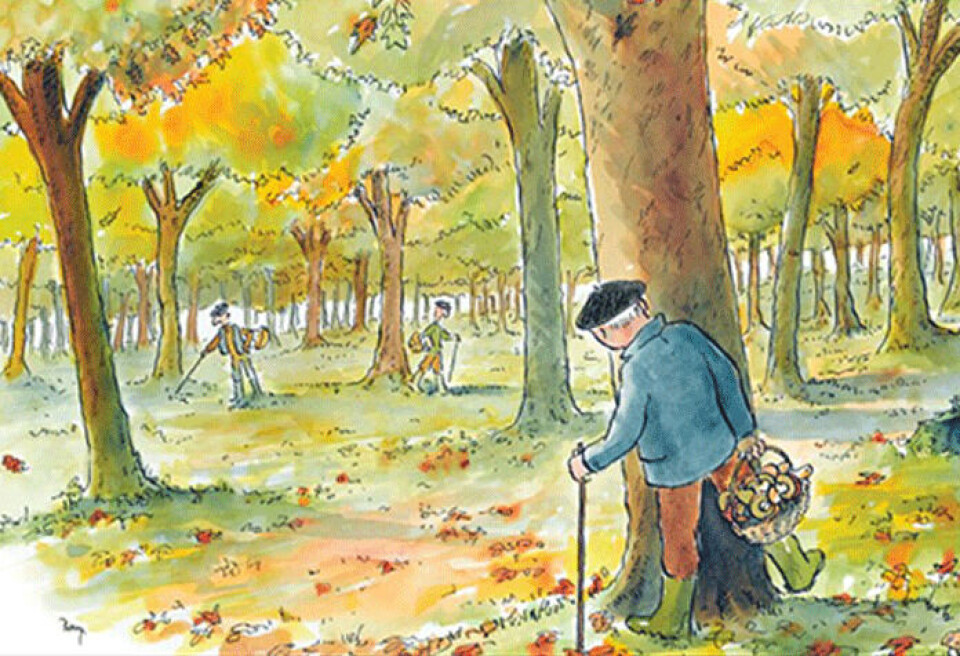

French woodland: Who owns it, the rules, and how to own your own piece

Contrary to fears that it is under threat, France is as wooded today as in medieval times

Our main image was drawn for Connexion by artist Perry Taylor. For more of his work see www.perrytaylor.fr

France is a land of big woods, small woods, commercial forests and wild forests.

The public perception is that woods and forests are under threat when, in fact, in 2019 their surface was much the same as it was at the start of the medieval period.

Wood was used for fuel, building ships and houses, or just cut down to make space for farms, until in 1850 there were 8.5 million hectares left. Since then, the surface of woods and forests has continued to grow and in 2019, the latest figures available, there were 16.5 million hectares.

The most spectacular growth has been on steep hills and in the mountains, areas where cleared fields were small and difficult to get to. When tractors replaced horses, these areas were the first to be abandoned and woodland regenerated.

Unlike the UK, where many farm woods have not had trees cut since the end of World War One, many of France’s woods and forests have been cut regularly. Wood was the main source of heat in the countryside until very recently.

The attachment to woods is strong – many buyers of old farmhouses find that woods come with the house, the previous owners having hung on to them even after the rest of the land was sold.

It is not uncommon for what looks like one wood to have several owners. Boundaries are often not marked but handed down through the generations, sometimes based on one distinctive tree or rock formation.

Estimated 3.5 million private wood owners

Overall, three-quarters of the woods and forests in France are owned privately, with an estimated 3.5 million owners.

The state and local government authorities own the rest. The wildlife charity Aspas has also bought woodland to make hunt-free zones.

Walkers’ rights depend on the ownership status. In public forests, you can ‘officially’ pick up to five litres of mushrooms or a handful of berries per person, for personal consumption.

Collecting fruit or mushrooms from a private forest requires authorisation from the owner, even if it is accessible. Owning woodland does come with its share of paperwork.

Since 2011, any private owner of 25 hectares of forest or more has to have a plan simple de gestion (PSG), detailing how they intend to use the forest.

Owners of woods between 10 and 25 hectares are advised that they too will have to have a PSG at some time in the future so to prepare one now.

A PSG must include a description of the holding, and an outline of economic, environmental and social factors which might affect it, including details of woodcutting plans and replanting.

The idea is to make sure owners are aware of the importance of managing their woods and ensuring they are passed on to future generations.

For large forests bought as investments, a règlement type de gestion sets out a management plan for the forest, with the idea that qualified forest management experts, or officers from the state’s Office national des forêts, are involved and the plan is approved by a Centre Régional de la Propriété Forestière (CRPF).

A final document, Code des bonnes pratiques sylvicoles, is drawn up by the CRPF, and owners can sign up to the code to follow sustainable practices.

They can get a certificate showing wood from their forest is grown sustainably, and so a better price.

In addition, there are often local initiatives to try to both exploit and ensure the sustainability of woods and forests.

In parts of Charente and Dordogne, local authorities have tried to impose a global management plan for woodland, amid worries that younger generations of town dwellers who inherit small woods from their parents are doing nothing to manage them.

Woods as an investment

Investing in woods and forests has long been encouraged.

The biggest tax advantages come from groupements forestiers d’investissement, which are seen as investments in small- and medium-sized businesses, and so allow a 25% reduction in income tax on the amounts invested. You must pledge not to sell until December 2027 to benefit.

For people subject to impôt sur la fortune immobilière (IFI) – those with property worth €1.3million or more, with main homes having a reduction of 30% – investing in a forest can bring reductions of up to 75% in IFI, and also be advantageous to heritors.

Even people who buy a small wood by themselves for pleasure or for a long-term investment can benefit from a 25% reduction in tax as long as all the formalities, including a voluntary PSG, are carried out.

Rural banks often have a forest and woodland expert who, as well as knowing which woods are for sale, can help with formalities.

Average prices in France in 2020 were €4,280 per hectare of woodland, with the lowest price of €2,550 per hectare in the Massif Central and €6,640 in the Paris region and the north of France, according to the state-run Safer, a non-profit organisation which buys and sells rural land.

Yields on woodland investments have been steady at 1% or 2% a year for decades.

Small woods sold between friends can go for a lot less – stories abound of how the most expensive part of buying a wood is the notaire’s fees.

Downsides of owning a wood

Investing in woods and forest is not risk-free – the owners of the pine woods in Gironde which burnt in mid-July will have lost most of the value of their land – as forests are almost impossible to insure.

According to a 2019 report from the Senate, a third of France’s forestland is at risk of fires, with this figure predicted to rise to half by 2060.

Selling wood too can be difficult: many of the small, local sawmills and lumberjack firms which used to be a feature of French country areas have shut, and bigger companies are often not interested in buying small parcels of standing wood.

For firewood, local arrangements, where the cutter takes half the wood and leaves half for the owner, are common.

Incredibly, before the Covid pandemic, French tree trunks were being sent to China to be sawn, and then imported back to France as flooring or as simple beams.

Related links

MAP: Where are France’s most and least densely forested departments

National parks in France warn visitors to respect flora and fauna

French farmer grows crops without water, fertiliser or pesticide