-

Learning French: Have you ever dreamt in your target language?

From passive listening to active speaking, dreaming in French can indicate you are regularly practicing it

-

Learning French: what does fastoche mean and when should it be used?

Plus, can you guess the meaning behind more simple slang terms ending in -oche

-

Learning French: when and why do we say montrer patte blanche?

A French fairytale phrase for trustworthiness

Franglais ou Frenglish? The history of French resistance to English

For centuries, purists of the French language have tried to root out alien English words and phrases. Michael Delahaye charts some of the milestones – or should that be pierres de kilométrage ?

It started with food… when the Normans invaded England in 1066, they brought with them both their cooking skills and their language.

So, to the Old English words cow, calf, swine and sheep, the new rulers added boeuf (beef), veau (veal), porc (pork) and mouton (mutton).

The Saxon peasants, though subjugated, quickly realised that there was an opportunity: by using the English words for the live animal and the French words for the slaughtered meat, they could subtly imply that the only good Norman was a dead Norman.

The battle lines were drawn. Over the centuries, both sides have been guilty of linguistic larceny. British fashionistas have long plundered the French word-pool to appear more chic, soigné and generally au courant and à la mode… while, at a more utilitarian level, a cul-de-sac has a certain je ne sais quoi totally lacking in a dead end.

And when did you last hear someone refer to a fatal woman, a piece of resistance or a sanitary cordon?

Suffering from a sideways fart

Some of the best French expressions, sadly, never made the cut. My French-speaking grandmother used to say of a whingeing friend that she suffered from un pet de travers – a sideways fart.

Initially, the French were more resistant to the cultural exchange, restricting themselves to such basics as le weekend, le sandwich and le bifteck (close enough), but in recent years they have more than made up for the slow start.

These days mon boulot frequently becomes mon job while, in their spare time, our sportier French friends take to le jogging or le running, wearing les baskets, les tennis, or for the uber-trendy, les sneakers du moment… in fact, life these days is often more of un challenge than un défi, although the word originally came into English from the Old French chalonge. What goes around comes around.

Even to the cloth ears of an Englishman, there are some dissonant horrors.

Un relooking – meaning a make-over – must rate as one of the greatest crimes against the French language, up there with stopper and scotcher, to sticky-tape something.

How long before French consumers are offered their breakfast muesli in pochettes resealables?

The founding fathers of linguistic purity

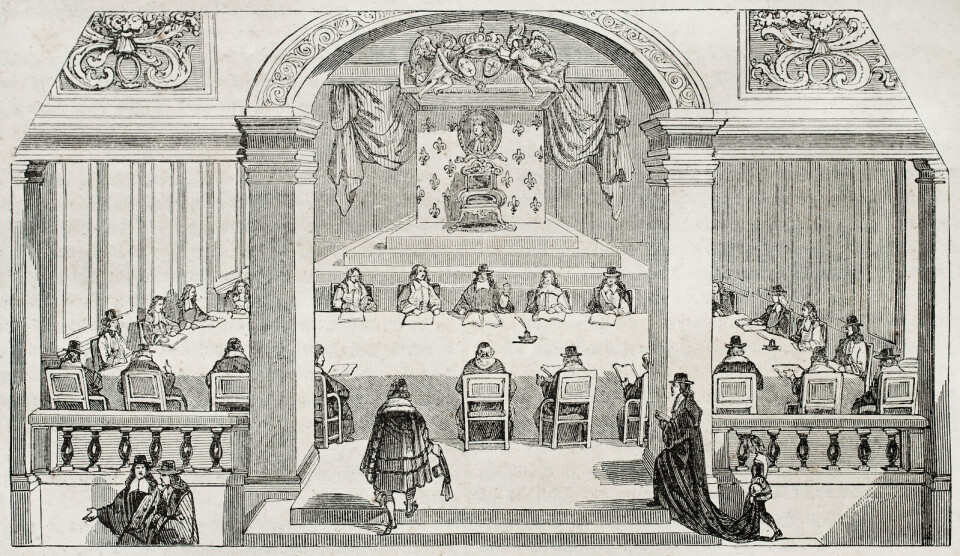

Cardinal Richelieu must be spinning in his vault. It was he who, back in 1635, founded the Académie Française to protect the purity of the French language.

With the coming of global mass media in the 20th century, it was always going to be a losing battle. But that didn’t stop the French culture minister Jacques Toubon from trying to verbally engineer an entire population by introducing a law in 1994 that required parallel translations of foreign words in official and commercial communications.

The reaction was revealing. Whatever the academics and politicians might have thought, those whose trade was words – the journalists and humorists – generally derided such a Canutish attempt to turn the linguistic tide.

The result was a spate of jokes about “Mr Allgood” (English translation of tout bon), culminating in a parody dictionary entitled Sky Mr Allgood! Parlons français avec Monsieur Toubon.

Reducing the minister’s injunction to its literal absurdity, author Jean-Loup Chiflet (alias John-Wolf Whistle) advised that un bulldog should henceforth be un taureau-chien; le feedback, nourriture arrière; and, warming to his theme, un sweat-shirt, une chemise de sueur…

Enter the internet

But the decisive battleground has been in cyberspace. Those of us who lived in France in the 1980s fondly remember the Minitel, France’s innovative prototype of the internet, along with its own native vocabulary.

Information aside, you could use it to catch up with the news, buy rail tickets or indulge in online dating, via discreetly anonymised chat rooms – the notorious messageries roses. Best of all, the hardware was free to anyone with a phone line.

But by the late 1990s, the Minitel was being superseded by the Anglo-Saxons’ World Wide Web and, with it, the triumph of English/American. Les minitélistes morphed into les internautes.

That said, a handful of French cyber terms have survived. Télécharger, which predates the Minitel, continues to hold its own, even if it fails to distinguish between download and upload.

To make the distinction, you must – rather clunkily – specify descendant or montant.

Curiously, the most zealous upholders of French linguistic purity are not the French but their Québécois cousins, the French Canadians.

While the French have largely accepted email, podcast and selfie, the Québécois insist on courriel, balado and égoportrait. They have even tried to introduce baladodiffusion (a conflation of baladeur and radiodiffusion) as a general term for podcasting. In the time it takes to get through all seven syllables, you could have played an entire balado.

Judging by common usage, you might think that in France itself, pragmatism has won out over purity.

While queuing in my local post office, I noticed an advertisement for La Poste’s new mobile online banking service, Ma French Bank (no, that is not a mangled mistranslation but exactly as it is written).

After a double-take, I consulted the 50-something French woman behind me.

Wasn’t she irritated, even offended, by such an ugly and unnecessary Anglicism? She shrugged. “On troque.” One swaps.

She is right. These days, when French manufacturers want to give their products an extra marketing edge – or, as we British might say, a certain cachet – they are as likely to label them Made in France as Fabriqué en France.

It is a strange and occasionally schizophrenic world in which journalists and copywriters now regularly hedge their bets.

So when the respected magazine Marie Claire can’t decide between rooftop and toit terrasse, it uses both in the same headline.

However, just when you might think the Anglo-Americans have finally won, the mayor of Marennes-Hiers-Brouage in the Charente-Maritime, Mickaël Vallet, leads a personal counter-attack and bans the telecom company Orange from his town until they rename their Orange Truck a Camion Orange.

Citing Toubon’s Law, he declares in words needing no translation: “Les anglicismes sont une aggression contre les citoyens.” Battles may have been lost but the war continues.

What about les British?

A final thought: why don’t the British get as worked-up as the Franco-phones over the influx of cross-Channel vocabulary?

Much of today’s English may be Norman-French in origin but, when it comes to protection and pedantry, we are no less passionate about our mother tongue, as testified by the regular media rants about the misuse of the apostrophe or the way imply/infer, apprise/appraise, uninterested/disinterested have become interchangeable.

Yet I have never come across anyone – academic, politician, journalist or layman – complaining about our many French imports.

Au contraire, we cherish them!

Just take a close look at the royal coat of arms on the front of your British passport.

Every word is French: “honi soit qui mal y pense” in the centre, above the motto “Dieu et mon droit”. Even the word passport is a throw-back to the French passport.

The new post-Brexit passports will revert to blue, symbolising the nation’s regained “independence”. But the French will remain.

So perhaps it is time for some reciprocity: un échange cordial.

Cher Monsieur le Président… if your fellow citizens can swallow Ma French Bank, how about changing the motto of the Republic to liberty, equality, fraternity…in English.