-

Breton name bowls: 'People are no longer interested in the traditional craft'

These bowls have become a staple of French cabinets and breakfast tables, but how are they really made?

-

French crafts in focus: Chaudronnier

Metalworker Jean-Louis Martini specialises in building and fixing vehicles, particularly motorcycle parts

-

Vegetable base for new fake leather invented by French scientist

No plastics used in innovative new product, called Phyli

'Patience and creativity' needed to create stonemason art from France

Marlie Kentish Barnes has been a stonemason, lettercutter, and stone-carver for 30 years and now mostly creates personalised funeral memorials and individual jobs to order

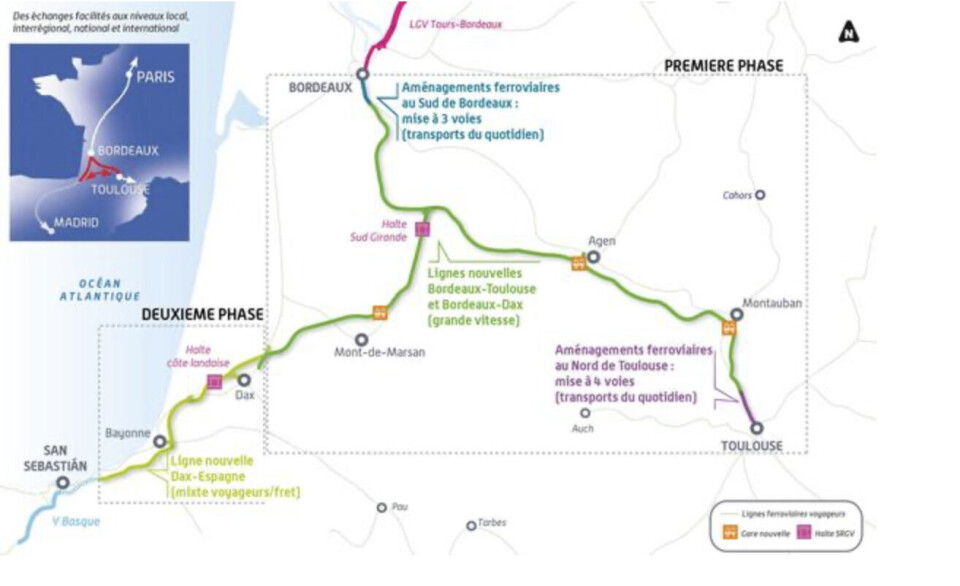

Ms Kentish Barnes has been in France for the past 15 years and is based at Rabastens, Tarn, about half an hour from Toulouse (see artfuneraire.fr or sculpture surpierre.fr).

She began her career studying visual arts at university in the UK, but always knew she wanted to work with stone.

After her degree, she enrolled for a City and Guilds diploma at Weymouth College to train as a stonemason.

“Stonemasons are qualified artisans, like cabinetmakers in wood, trained to work to an exact set of dimensions that require accuracy to the millimetre,” she said.

“It can take a good five working years to become competent with the tools and skills and to be able to take on ornate and challenging work.

“After Weymouth College, I had the chance to work on some wonderful projects, both modern and historic, and including work for the National Trust.

“I then moved to Sydney, Australia, as a stonemason before coming to France.”

Ms Kentish Barnes has used her skills as a stonemason to build her own business creating commissions for clients using letter-cutting, relief-carving and sculpture techniques.

This lets her concentrate on the creative and decorative aspects of working with stone and she says she loves the challenge of coming up with designs to match different clients’ wishes.

Her work can vary from a geometric design, such as a Celtic cross, to delicate flowers around a headstone, to the sensitive rendition of Francis of Assisi with a bird in his hand.

“First, I discuss the project with the client. I make drawings and we then decide the final design together.

“I order the stone from a quarry and I prefer to go and fetch it myself so I can see and touch the stone and even take a chisel to it if it is a stone I haven’t yet used, to make sure it is the right quality for the project. I work mostly in limestone and sandstone, and I love using slate for lettering as the letters cut will always remain paler over time.”

She then takes up her tools: “For letter-writing, I use a small hammer which is halfzinc and half-lead to absorb any vibration, and fine chisels made out of tungsten, which is very tough and does not often need sharpening. I also use tungsten tools for bigger-scale work and instead of a traditional wooden mallet, I use one made of nylon. I have had the same one since I started my career in stone.”

It is impossible to say how long a job will take. She said: “Nothing about working in stone is fast, and there are so many variables.

“One letter could take on average 20 minutes, plus 10 minutes for the drawing, but that depends on the size, the stone and the choice of letter.”

She feels there is a common misconception that a tailormade gravestone will be more expensive than one in a funeral parlour’s catalogue.

“I did some research and found prices are more or less equivalent. One of my gravestones with clematis flowers in relief and writing costs the client around €2,900. Stone is not an expensive material and I can adjust a design to work with the client’s budget.”

In France, Ms Kentish Barnes says the art of letter-cutting and relief-carving almost died out when cement and modern materials became very popular.

Traditional skills such as letter-cutting and stone-carving became unfashionable in the 1970s and the early part of the 1980s, but they have made a comeback.

She runs popular courses for professionals and the public.

“It is a pleasure teaching a skill people think will be difficult, but really it is about learning a technique. Once they have understood that, they can make something to be proud of. I often have pupils from a school for students who are perhaps behind academically and they always love it because they get so engrossed in the process.

“One difficulty to overcome is learning to take away to reveal the desired effect, rather than building up to make something, as you do if you work in clay, for example.”

She said you need patience and creativity to work with stone.

You must also enjoy physical work, and it helps to know something about the history of art and architecture and how to draw.

“Working in stone in the way I do, where I can be creative and earn my living, was a good career choice and I love it.”

To become a stonemason in France, you can study for a two-year CAP tailleur de pierre, a three-year Bac pro, either with an artisanat et métiers d’art option arts de la pierre, or intervention sur le patrimoine bâti, option pierre.

There is also a Brevet professionnel, a two-year BP métiers de la pierre, and a Brevet technique des métiers supérieurs, following on from a BP (tinyurl.com/47rma46c)

The highest qualification is to study with the Compagnons du Devoir.

There is also a two-year Brevet des métiers d’art to become a graveur sur pierre.

Related stories

'We are proud to continue the craft of traditional straw brooms'